When less is more: How the oversharing epidemic gave rise to digital identity theft

Since the advent of the digital age, we've been slowly but surely hooked on online services. Hardly an hour goes by without us doing something online: whether it's liking a post on social media, shopping, ordering an Uber, watching Netflix, swiping on Tinder, transferring money or accessing a remote desktop. The names of the companies and the things we do may vary — perhaps, you're more into online trading than shopping and prefer gaming to binge-watching shows — but the fact remains: we have all grown our distinct digital identities that may or may not correspond to our real selves.

We entrust some of the information to the care of governments and private companies. We knowingly and unknowingly share our data with tech giants, who track our digital footprint via increasingly sophisticated tools. That information also becomes part of our digital identity.

One man has famously said, data is the new oil, and another less famously argued that it was rather the new nuclear power to the extent it can be weaponized to cause harm. In a world where everything can be bought and sold, a person's complete digital life — digital identity — has become a hot commodity. If stolen and abused, it may bring its real prototype down.

![]()

According to a recent Dark Web Price Index report, a digital identity — that is complete information about a person's accounts — can be bought on the dark web for less than $1,200. A hacked Facebook account goes for $45, a 1-year Netflix subscription for $25, a selfie with holding a forged US ID will cost one about $120, the same as credit card details with account balance of up to $5,000. Crypto accounts are also not immune from theft: the cost of one crypto account varies from $90 to $250.

And criminals tend to buy in bulk. 50 hacked PayPay account logins are sold for just $150, and 10 million USA email addresses can be bought for $120. The rules of dark marketplaces increasingly resemble that of legitimate ones: sellers offer discounts and coupons, while buyers leave product reviews.

But the sad truth is that often there is no need for malefactors to splash out on a digital identity — if only out of convenience — users provide the bulk of our personal data themselves, willingly and for free.

Why would someone need my identity?

Once a digital identity or at least its part falls into the hands of criminals, it can be abused in a multitude of ways: it can be resold, it can be used for blackmail, for money, your "digital identity" can attempt financial or medical fraud, or even murder.

The US authorities estimated that $100 million in COVID-19 funds were laundered through online investment platforms via accounts set up with stolen identities. In one case, criminals used a man's identity to claim $28,000 in relief funds for a non-existent business, then they opened an investment account in his name and a bank account to transfer the money to.

The theft of medical data is, perhaps, not the first thing that comes to mind when you think of digital identity theft. Yet, there is a burgeoning market for insurance numbers. A Medicare number can fetch as much as $1,000 on the dark web, compared to just $1 for a Social Security number. In one such case an elderly man racked up a hefty bill for an array of medical procedures and multiple doctor visits he had never received.

Who has not at least once mistaken a fake social media celebrity profile for a real one? But what if an imposter creates a fake profile for you, dupes other people into believing it is the real you and swindles them? The practice is known as cloning. A fraudster creates an account, makes it look identical to the real one with the help of the information a victim has generously shared online, and reaches out to that person's "friends". "Facebook friends" are a special breed of "friends", so one should not be surprised that they buy into the fraudster's tall tale. That happened to one Indian man, whose Facebook acquaintances were asked to channel Rs 10,000 ($136) to the criminal's account.

And money is a cheap price to pay, as some victims pay with their lives. A particularly twisted form of cloning is catfishing, that is when an imposter assumes another person's online identity to enter into a romantic relantionship. It is so widespread that it even has its own show on MTV. An Australian woman took her own life in 2018 years after a female catfish posing as a male actor struck up a romantic relationship with her online, and tricked her into sending intimate photos and videos.

Another extreme example — fraudsters might use real photos of a sick child to raise money off it.

They can register with online casinos, crypto exchanges, and marketplaces using just a passport scan. A SIM swap scam — when a phone company is tricked into assigning a victim's number to a new phone — comes into play if there's a need to clear the two-factor authentication hurdle. Twitter's Jack Dorsey infamously fallen victim to the scheme in 2019.

If you lose access to your account in a hack or a social engineering attack, it can be repurposed for spam, advertising and to imitate a real person when perpetrating fraud.

Even after your death your digital identity may not be able to rest in peace. A form of identity theft known as 'ghosting' is commonly used by criminals to claim tax returns on behalf of the recently deceased. The US government estimates that the identities of 2.5 million deceased Americans are stolen by fraudsters every year.

Safe to say, our digital identity is out here waiting to be abused. And if you were lucky enough to not fall prey to fraudsters yet, then this is more of an exception that proves the rule.

How our digital identity falls into the hands of fraudsters?

There are two principal ways in which a digital identity may become a tool in the hands of criminals: victims are either forced to reveal it or do it voluntarily.

When we hear the word "cyber crime", the first image that springs to mind is that of a hooded man — the hacker. Indeed, the data stored by government entities, medical institutions, and companies can be breached in a brute force attack or a social engineering attack. The former relies on a trial and error method of hacking passwords and encryption keys, while the latter usually involves some form of communication between attackers and an unsuspecting victim. A breach of a popular online trading platform in India last year saw the data of over 3.4 million customers being put for sale. It included customer ID, email ID, contact number, trade login ID, branch ID, and location.

Then, there are malware attacks. A bad actor can infect a victim's device with a data-stealing malware, which can, for instance, record keystrokes as a victim logs into accounts, harvesting the information stored by the browser, including cookies and passwords. As a result of such an attack, a user's browser fingerprint becomes exposed. Resetting passwords won't help while a bug is present in the system. Then the data can be sold on the notorious invite-only Genesis marketplace or somewhere similar.

The list will not be complete without phishing emails and websites. Scammers forge an email from a legitimate entity and prompt a recipient to disclose their personal data in a response. The US Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has constantly warned Americans that scammers are using the agency's logo and name to steal secret access data and credit card and bank account numbers.

Credentials and other data can also be stolen through spoof websites that are designed to look exactly like the real deal. In November 2020, the account data of scores of PUBG Mobile gamers was exposed as a result of a fake giveaway via hundreds of phishing pages.

We can detect malware, block phishing websites, employ sophisticated security protocols — it will help, to an extent, but even if we deprive malefactors of all the tools, they will continue to tap into an incessant stream of data. How so?

The root cause of the problem is the modern tendency to overshare. We post holiday snaps, geotagged, so everybody could see what posh hotel we have checked in. We post photos from the front porch of our newly-bought family home, geotagged and with the house number visible, cars proudly on display in the driveway.

We reveal our birthdays, health issues, our interests and bucket lists — all while tracking algorithms silently listen and tailor ads to us.

What's more, some of us are careless enough to upload identity documents to social networks. A brief search on one popular social network returned numerous scan copies of documents that appear to be valid.

Such oversharing can backfire. And it did for an Insta-famous fraudster by the name of 'Hushpuppi'. The Nigerian was a mastermind behind an email scam operation, and flaunted his luxurious lifestyle online. The FBI used his social media accounts to collect evidence and track him.

Once in a while we hear about ordinary people being fired because of the content they post, as was in the case of a Russian paramedic who took selfies with dying patients.

A British bank estimated that the effects of 'sharenting', that is when parents reveal names, ages, home addresses, places of birth, names of pets and sport teams, and other personal data about their children, will account for two-thirds of identity fraud cases targeting young people by 2030, and will cost them £670m a year.

Perhaps, you remain tight-lipped. But still, the demands of the digital age require us to share our data. We post elaborate CVs on job websites, create dating profiles, and take part in online questionnaires.

The consequences

As we have already seen, the consequences of digital identity theft can be truly catastrophic. You can unknowkingly finance terrorism, run over someone, defraud the government, or swindle someone out of thousands of dollars. Your reputation can be tarnished if your likeness is used to scam people, to lure someone into a romantic relationship.

Criminals can use information that you've shared online to guess your passwords (especially if it's your grandma's birthday or a pet's name) and break into your accounts, stealing your money and services.

Moreover, your health or life can be in danger. Imagine, you go to a hospital to get a test done, but a doctor tells you that you already had that test done two weeks ago. Or your real health parameters can get mixed up with that of a fraudster who abused your insurance.

And it's not only your reputation and finances that might suffer, but that of your company. Todd Davis, CEO of LifeLock, Arizona-based identity theft protection company, notoriously made a laughing stock of himself after he put his social security number on billboards and in TV commercials, claiming that the company's credit monitoring service would make "personal information useless to a criminal". To hardly anybody's surprise, except probably Davis's, the CEO's identity was stolen at least 13 times. His social security number was abused to obtain a loan as well as to open multiple accounts that all had outstanding debts by the time he found out about their existence. LifeLock was ordered to pay a $12 million fine for deceptive advertising.

According to the 2022 Data Breach Investigation Report by Verizon 82% of data breaches targeting companies involve the "human element". Phishing, use of stolen credentials and manipulating an employee into disclosing confidential information ('pretexting') make up the top 3 social engineering techniques that criminals use.

What are the chances your identity will be stolen

The more apps, electronic devices, social media and online service you use — the more likely you are to fall victim to digital identity theft. We leave chunks of personal data on each of our devices, share it with every app we use — the same goes for social media. You are at risk if you are an active member of numerous public groups and post personal information about yourself (about your financial situation, about your children's well-being) for everyone to see.

If you take part in online questionnaires, quizzes, giveaways and paid surveys, you're also playing with fire. They can be tools to harvest your data, which can then be sold to spammers or compromised in some other way. Resumes, student applications that you post online and that reveal your personal details also make you vulnerable. In the end, it is the amount of the publicly available information that makes the difference.

Disregard for basic protection measures, such as installing anti-virus software, enabling two-factor authentication or setting up a strong password increase the likelihood of your digital identity being compromised.

How to decrease the risks

You cannot unplug yourself from the world, but you can shrink your digital footprint and at least make criminals work hard if they want to lay their hands on your digital identity.

- Share less on social media — the internet never forgets. Even if you remove the post afterwards, it can still be screenshotted or retrieved through web archives. Resist the urge to share your purchases and information about your loved ones or where you live. Be mindful when geotagging photos and tagging others in them.

- Do not upload copies of your ID documents, such as passports, drivers licenses to your social media accounts. Do not send your documents, especially your selfie with an ID card, to random third party services “for identity verification” unless absolutely necessary.

- Carefully study privacy policy before participating in an online survey or a questionnaire and find out what your answers can be used for. If no such policy exists, then it’s better to forgo that survey altogether. Even if the privacy policy does not contain any red flags, the pollster can leak the data anyway. So the fewer questionnaires you take, the safer you are.

- Be wary of "too good to be true" discounts and generous giveaways offered by well-known companies. Make sure you are not on a phishing site, and contact a representative of the company to verify the campaign if you're in doubt.

- Allow only those cookies that are essential to the functionality of the website if you don’t want advertisers to track you across the web and bombard you with ads.

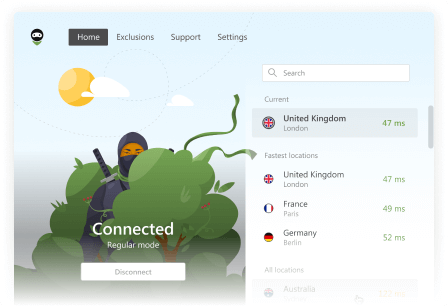

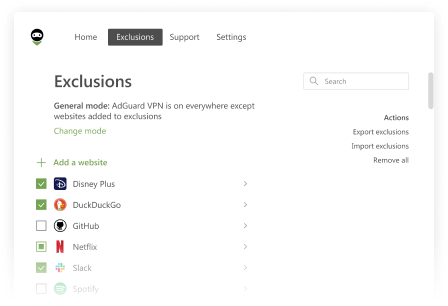

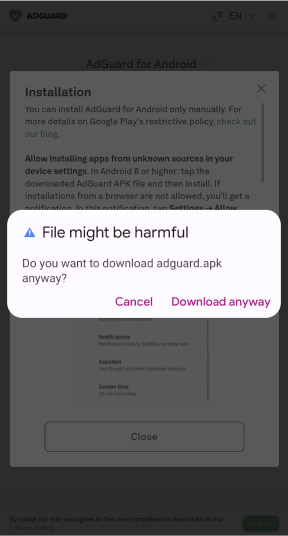

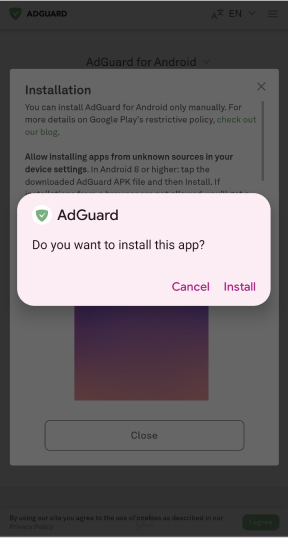

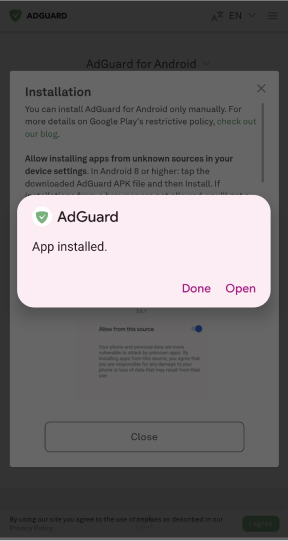

- Use ad blockers that are trustworthy and have not been caught red-handed leaking data. You can also switch to a privacy-focused browser, use a VPN or a DNS server.

- Set strong passwords that are not reused across your other accounts or devices, and use password managers.

- Enable multi-factor authentication where possible — it will help protect you from unsophisticated hackers.

- Install and timely update antivirus software, make sure you have enough space in your device for the updates.

- Give your apps only the most necessary permissions

As for the documents that we have to email our employers, professors, insurers and others online, make sure you send them via an encrypted email service and that your mail is password-protected.