Blocking real-world ads: The future or a fix no one asked for?

The notion that ads are a nuisance that must be blocked by whatever means necessary isn’t new. It goes way back, long before the Internet became overrun with banners, pop-ups, video ads, and all the other junk we deal with now. In the early days of the web, when it was still mostly the domain of the tech-savvy free of digital noise, the main battleground for ads was traditional media: TV, newspapers, and, sure enough, billboards.

And even though we now spend a growing chunk of our time online — sometimes even while standing in a store or walking down the street — the problem of infoxication and ad overload in real life hasn’t gone away. Flashy shop signs, towering digital billboards and rotating displays still manage to catch our eye whether we want it or not.

Sure, we can try to tune them out, but they do sneak back into our line of vision. Is the solution just to block them? It’s an idea that sounds futuristic, maybe even a little extreme. Some might argue that doing so risks cutting out more than just noise. Still, for many, the temptation to reclaim control is too strong to ignore, especially since much of what passes for “messaging” today feels more invasive than informative.

So it’s no surprise that developers are now trying to bring the logic of digital ad blockers into the physical world. But is it actually working — and, most importantly, is it doing more good than harm?

New take on real-life ad blocking: repurposing Snap’s AR glasses

The idea of blocking or modifying ads in real life has been floating around for a while, and there have even been a few attempts to make it happen (we’ll get into some of those later). But as technology keeps moving forward, especially with the advances in image recognition and generative AI, the idea is starting to feel more and more feasible.

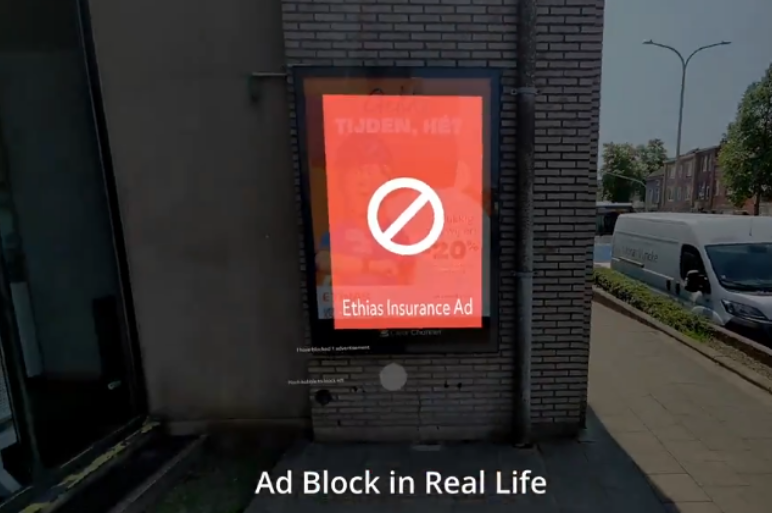

The latest attempt to crack the challenge of real-time ad blocking comes from Stijn Spanhove, a Belgian programmer who built an ad-blocking app compatible with Snap’s fifth-generation AR Spectacles. To build the app, he used a library and APIs shared by Snap on its GitHub. The app combines the capabilities of the glasses with those of Google’s Gemini AI to detect real-world advertisements (the kind plastered on billboards, packaging, and newspapers) and replaces them with a red square.

That red overlay also displays the brand name and the type of ad it removed (e.g. “Billboard ad”). So far, the app can only be used with Snap Spectacles, but over time it might become available for other augmented reality glasses brands like Apple Vision Pro and Meta Quest.

In the demo video, which shows the app doing its job on city streets, the ads are covered with semi-transparent red rectangles, just transparent enough that you can still see the ad underneath. One could argue this kind of overlay is even more annoying than the ads themselves. In fact, it might just grab your attention in the worst possible way — like flashing (red) lights in your face.

Source: Stijn Spanhove/X

That said, since this is the app’s first raw version — more of a rough outline of how things work than anything — any design flaws are likely to be ironed out in future updates. Some users have already weighed in with suggestions, including the idea of moving away from the harsh, almost alarming “red square with a no-no sign.”

Spanhove already said that he was considering using generative AI to replace the red rectangles with something more pleasing to the eye. “Let’s say you like cats, let’s personalize it,” he said, referring to the idea of using inpainting to tailor what users see in place of ads.

Other users have floated creative alternatives like swapping the overlays with top items from your to-do list, a potential boon for planning junkies who’d rather be reminded of their priorities than see another ad.

Source:X

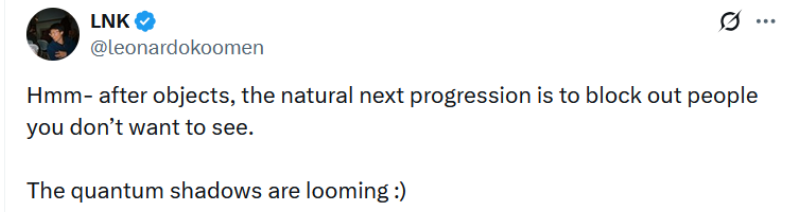

And you can’t help but wonder: what else could be blocked using the same method? “After objects, the natural next progression is to block out people you don’t want to see,” one user noted, channeling Black Mirror’s White Christmas special from 2014.

In that episode, the characters could block the individuals they did not want to see or hear from in real life: they were reduced to blurry, voiceless silhouettes, completely cut off from their perception.

As we’ve mentioned before, not only is the concept not new — implementation isn’t either, as you’ll see in the following section.

From They Live to Brand Killer

The idea that you can solve the problem of visual clutter by literally blocking it out of your vision has been around for decades. And Black Mirror wasn’t the first to come up with it.

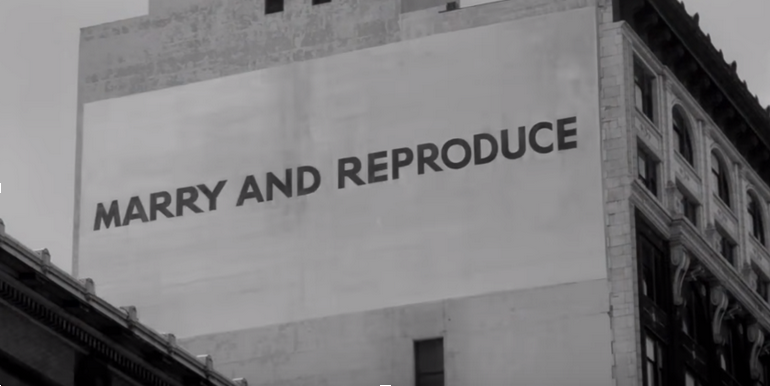

John Carpenter’s 1988 film They Live is likely a source of inspiration for some of today’s developers. In the movie, the main character discovers a pair of sunglasses that reveal the world as it truly is. As he walks the streets of Los Angeles, he sees that all the ads have been stripped down to their hidden messages, slogans like OBEY, MARRY AND REPRODUCE, DO NOT THINK, and other equally authoritarian commands serving the interests of those in power.

Top: the original ad in They Live.

Bottom: the same ad as seen through the ad-blocking glasses.

Source: YouTube

Moving from concept to real-life prototype is always the hardest part. The first attempts to bring this idea to life date back a decade. One such example was the Brand Killer glasses, built by a group of students during a weekend hackathon in 2015. The setup included a pair of virtual reality goggles, a small screen mounted on top of them, and a camera to scan the surroundings for brand logos and blur them out. The prototype was cobbled together on a shoestring budget, just $80 worth of raw materials.

Brand Killer. Source:YouTube

Blurred out logo using the Brand Killer goggles

The Brand Killer creators said at the time that they had originally aimed to blur not just the logo, but the entire ad, though that turned out to be too ambitious for a weekend hackathon. “We considered developing a system where a logo would be recognized on the advertisement, the edges of the ad would be detected, and then the whole ad would be blocked out.”

They also acknowledged a limitation of their approach: identifying ads in the real world isn’t as straightforward. “Besides that, without some sort of clear distinguishing factor like a logo, it can be fairly difficult for humans to discern what is an ‘ad,’ let alone for a computer.”

And they had a point. Unlike digital ads, which are typically served via structured elements, scripts, and by known advertising networks, making them easier for browser-based ad blockers like AdGuard to detect, physical ads don’t follow any standardized syntax. On the web, an ad blocker can scan the code of a webpage, match elements against a set of filtering rules, and surgically remove them. In the real world, however, an ad could be a printed poster, a billboard, a screen, or even branding on clothing or vehicles. There’s no consistent format or metadata to parse, just pixels. That means any real-life ad filtering has to rely on visual recognition, which is far more complex and error-prone.

Apart from the Brand Killer glasses, there have been a few other attempts to block out information noise. In 2018, a group of artists, designers, and technologists came up with the IRL Glasses (IRL as in “in real life”), designed to block LCD and LED screens. The prototype relied on a phenomenon known as horizontal polarization, which made the effect possible, but also extremely limited. The glasses could block out TV and computer screens, but only of a certain type, and only as a whole. They couldn’t distinguish or filter out individual elements on the screen, and they didn’t work on other display technologies like OLED. Naturally, they had no effect on printed ads or any non-digital formats.

IRL Glasses at work. Source: VICE

Concluding thoughts

The idea of ad-blocking glasses isn’t new, and neither is the attempt to bring it to life. All the previous efforts, however, lacked precision and were either blanket, indiscriminate solutions like the IRL glasses that blocked everything, including useful content, or relied entirely on image recognition, which is notoriously imprecise. That’s especially true when it comes to ads that aren’t typical, don’t feature logos, and are designed to blend in, that is ads that look like anything but ads.

So, all in all, while it might be too early to dissect this idea in all seriousness, there are still a lot of unknowns. Yes, it’s cool, but is cool enough to be effective? And while the latest wave of ad-blocking wearables feels closer to functional reality than ever before, there are still major caveats. Without a clear definition of what counts for ‘ad’ in the real world — usually it’s something more ambiguous than a web banner or script tag — there’s a high chance this kind of ad blocking could end up being more of a distraction than a savior.

And maybe the real question is: how often do we actually want to block out the physical ads around us? For all the understandable frustration with advertising, many of us rarely feel an urge to erase it from our surroundings entirely. After all, devices like this don't just filter noise, they remove parts of the reality we live in.

If anything, the bigger concern may lie in the opposite direction: not that we’ll block ads in AR, but that ads will start being inserted into it. The real arms race may not be about removing ads from physical reality, but about fighting to keep the real world unaugmented with virtual reality ads. And when that happens — when the augmented experience becomes the default, and the default includes ads — that’s when we, as an ad blocker, will be ready to bring back the reality to you.

— Andrey Meshkov, AdGuard Co-Founder & CTO