Apple’s attempt at system-wide filtering API — is it good? AdGuard’s research

Apple’s approach to system-wide filtering has recently introduced an API that differs significantly from what developers are accustomed to. The changes it brings have prompted me to think of several new ideas about how filtering can be implemented at the OS level, making it an interesting case study for the future of content blocking.

While discussions at AFDS typically focus on browsers and web extensions — the environments where most content filtering happens — system-wide filtering presents a broader and increasingly relevant challenge. Examining the limitations and capabilities of Apple’s new API offers insights that can help inform improvements in browser-based filtering as well. But first, let’s explore what exactly we mean by “system-wide filtering.”

What is system-wide filtering?

System-wide filtering is essentially the ability to intercept and block web traffic of any application, not just browsers’ traffic.

Filtering traffic inside a browser has always been relatively simple thanks to browser extensions. Even with Manifest V3, the browser still provides a clear, well-defined API for content filtering.

When we up the scale and look at operating systems, we see that they are a completely different story. None of them offer a dedicated API for filtering content, so ad-blocker developers have to rely on platform-specific techniques, and each of them comes with its own drawbacks.

You might ask — why does system-wide filtering even matter? Can’t we stick to browsers and just block ads there? According to recent studies, browser-originated traffic makes up less than 15% of total traffic on mobile devices. On desktops, browsers still dominate with around 55–60% of the overall traffic, but if you check the numbers across all platforms, only about 30% of total internet traffic comes from browsers. The other 70% comes from apps.

And that’s where the real privacy challenge lies. Tracking inside apps is often far more invasive than on websites. Apps can access more personal data, interact directly with device resources, and use persistent identifiers that websites simply can’t. That makes the task of filtering the entirety of the device's traffic all the more important.

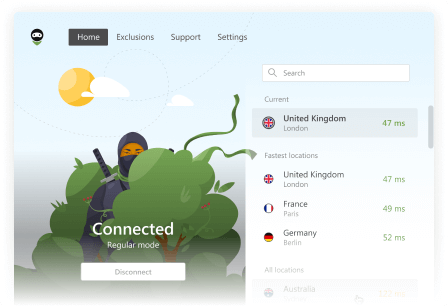

System-wide filtering has always been one of AdGuard’s core strengths. In fact, the very first version of AdGuard, released over 15 years ago, was a Windows application that blocked ads at the network level. Over time, we expanded to every major platform — and went even further by launching AdGuard DNS and AdGuard Home, two more products aimed at protecting the entire device (or even the entire network!), not just at filtering traffic within a single browser.

That’s what makes this topic especially interesting to me. There’s still a lot of room for improvement, and I’m glad to see that one of the operating system vendors — Apple — is finally paying attention to it.

How it works

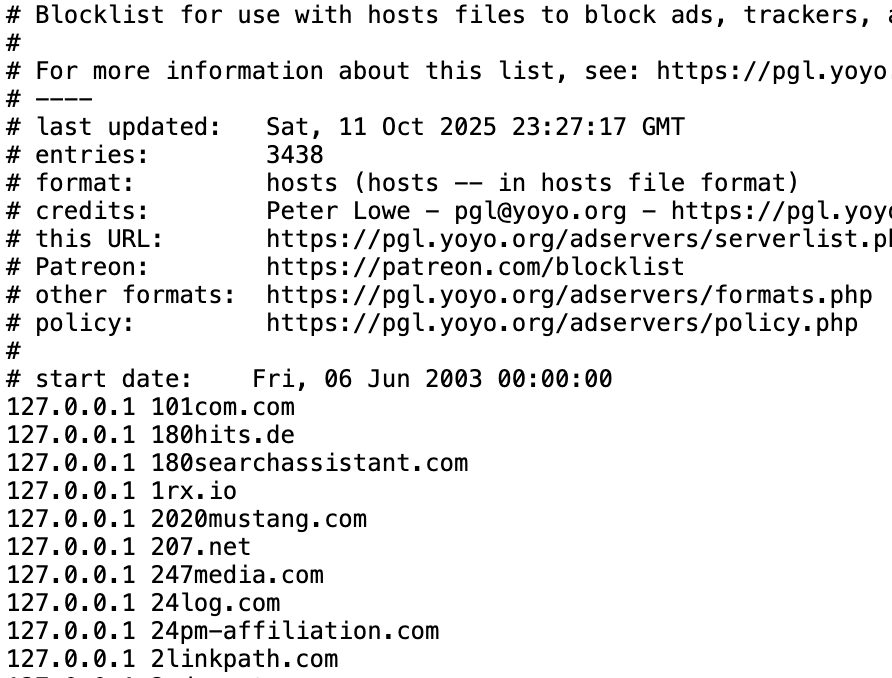

To understand my perspective, you first need to know how system-wide filtering began, how it works today, and what challenges the developers of ad blockers are still facing. A quick old-timer test: did you know that ad blocking actually began with HOSTS files that were used to redirect ad servers to non-existent IP addresses? HOSTS is a plain text file that maps hostnames to IP addresses, just like a DNS server does.

Snippet from Peter Lowe’s blocklist

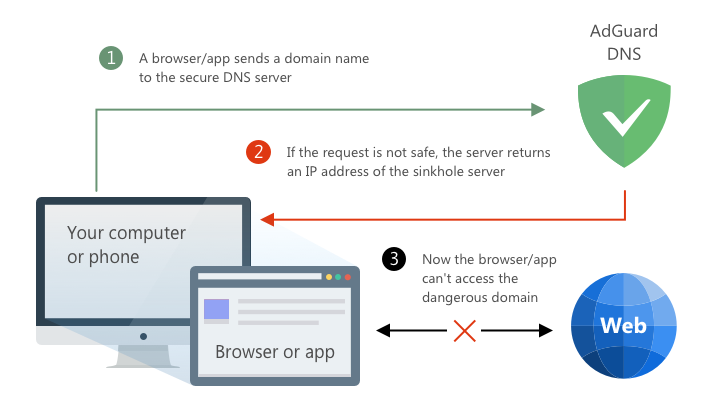

Of course, HOSTS files have their limitations: they’re static, they can only block exact domains, they’re hard to update, and they can be bypassed. Still, this was where it all started. Another common approach was DNS sinkholing — basically the same idea as HOSTS files, but applied at the DNS level so it works for many devices at once.

Example of using a DNS server to block access to a domain

It solved some of the problems, but had important limitations: it still could only block domains, and still could be bypassed. For that reason, DNS sinkholing helps in many cases, but it isn’t a complete solution.

Next came proxies — servers that act as intermediaries between your device and the internet for HTTP traffic. This approach was extremely popular in the early days of ad blocking. Many of the “classic” tools used it, such as Ad Muncher or even early versions of AdGuard. The screenshot you see here is from about 15 years ago, when AdGuard (spelled Adguard back then!) essentially worked as an HTTP proxy.

The main advantage of a proxy is that it can filter traffic based on full URLs and not just domain names — as long as the traffic isn’t encrypted. And even when it is, it still can see the domain name.

Whatever method you are using for system-wide filtering, the first technical challenge is intercepting traffic and routing it to your filter, be it DNS, proxy or anything else. Different platforms require different techniques:

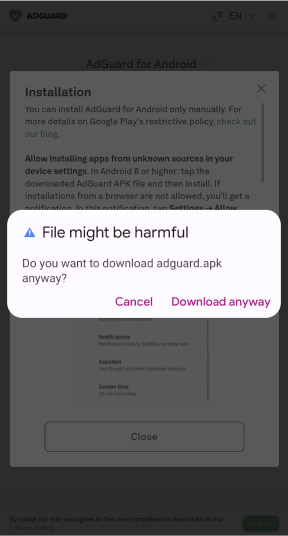

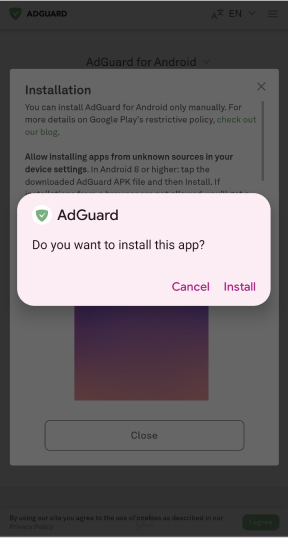

- Android: local VPN

- iOS: local VPN, DNS settings extension

- macOS: Network Extension (transparent proxy, DNS proxy)

- Windows: WFP/TDI/WinSock/NDIS drivers

I won’t go into details for every single one of these methods, there is no need for that. It’s enough to know that all of them are non-trivial to implement, easy to get wrong, and frequently run into compatibility issues. Yet they’re the primitives we must live with if we want to filter traffic at the system level.

Even if we solve all the previous challenges, there’s still one big problem left — we need full URL visibility for accurate filtering. Why is that important? Let me give you two examples.

- The first one is Facebook’s ad network. Facebook serves both legitimate content and tracking requests from the same domain —

graph.facebook.com. Without access to the full URL, blocking this domain would also break Facebook itself. - The second example is the IAB’s new proposal called Trusted Server. I won’t go into details here, but in short, it moves ad auctions to the server side and delivers ads from a publisher’s own domain — making them appear as first-party content.

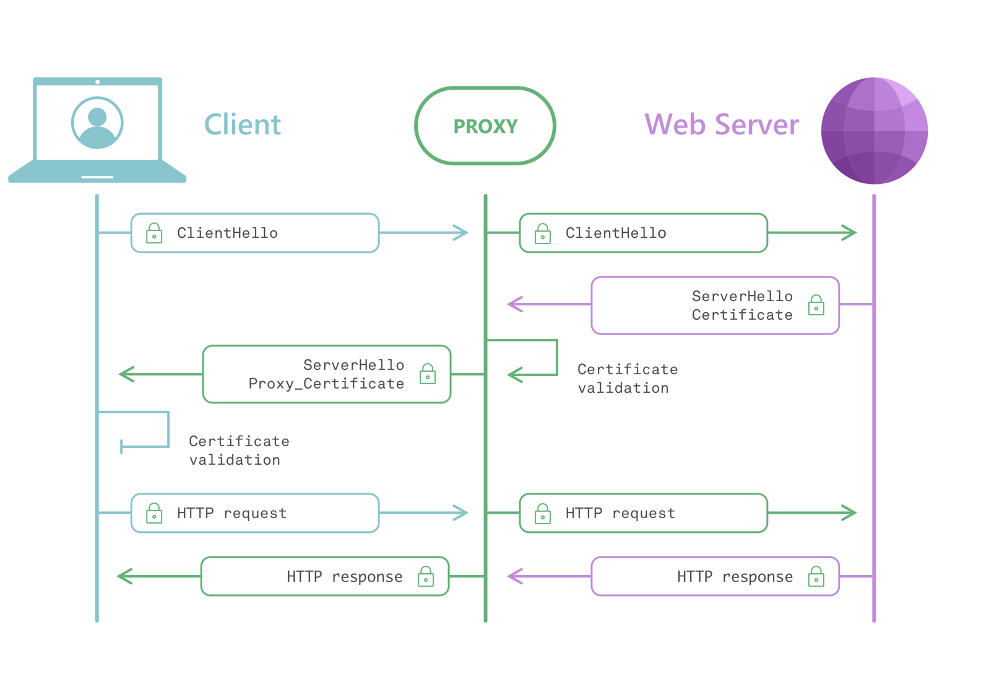

Right now, the only reliable way to inspect full URLs is to run a proxy with TLS interception. That, however, is an extremely complex task — but it’s something we still have to do.

Proxy + TLS interception diagram

So someone has to observe your traffic for filtering to work — whether it’s a browser extension, a VPN, or an antivirus. That’s simply unavoidable. Ideally, this processing happens locally, on the user’s device. That’s safer because the data never leaves the device. But even that requires trust — and history shows that trust can be betrayed. So while local filtering is preferable, it’s not a guarantee of privacy — users must still place their trust in whoever runs the filter.

So, what should an ideal system-wide filtering solution look like? There are several criteria it should satisfy.

- First, it has to support full URL filtering — that’s essential for precision.

- Next, it should offer broad filtering capabilities. Just blocking requests isn’t enough; sometimes you need to modify or redirect them, or inspect responses.

- It should also handle very large blocklists.

- And yet updates must still be fast and efficient.

- Of course, it must be private by design — meaning the content blocker shouldn’t need to know which websites a user visits; it would just apply the rules locally.

- Still, the system should give some kind of feedback — at least basic statistics or confirmation of what’s been blocked — to make it observable and useful.

- Finally, proper debugging tools need to exist. Both for developers like us and for filter maintainers who need to troubleshoot their rules effectively.

With this list in mind, let’s move on to Apple's URL filter.

Apple’s URL filter

About ten years ago, Apple became the first browser developer to introduce a dedicated content-blocking API. Now, a decade later, they’ve taken another big step — this time at the operating-system level. For the first time, Apple is providing an official API for system-wide URL filtering. On paper, this is great news. And frankly, it’s something we’ve been waiting for — an exciting opportunity for anyone working in privacy and network filtering.

So let’s take a look at how this API actually works. We’ll start with a very high-level overview.

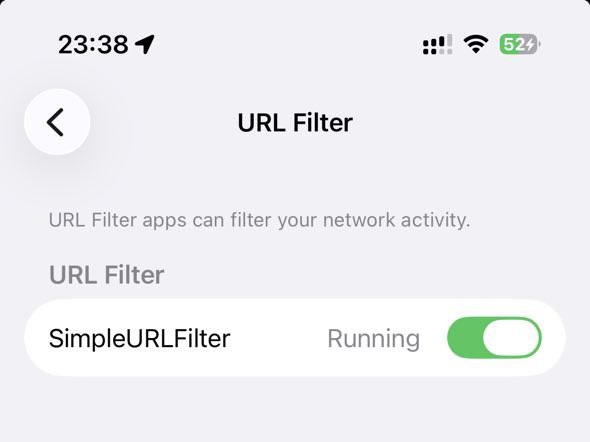

- First, your app registers a special URL filter within the operating system. This applies to both iOS and macOS.

- Then, to activate it, the system performs an authorization step — it communicates with your server to verify the configuration and credentials.

Once that’s complete, the filter enters the Running state, and from that point, the system starts using it to check request URLs. When the URL filter is active, it examines every web request made by any app on the system.

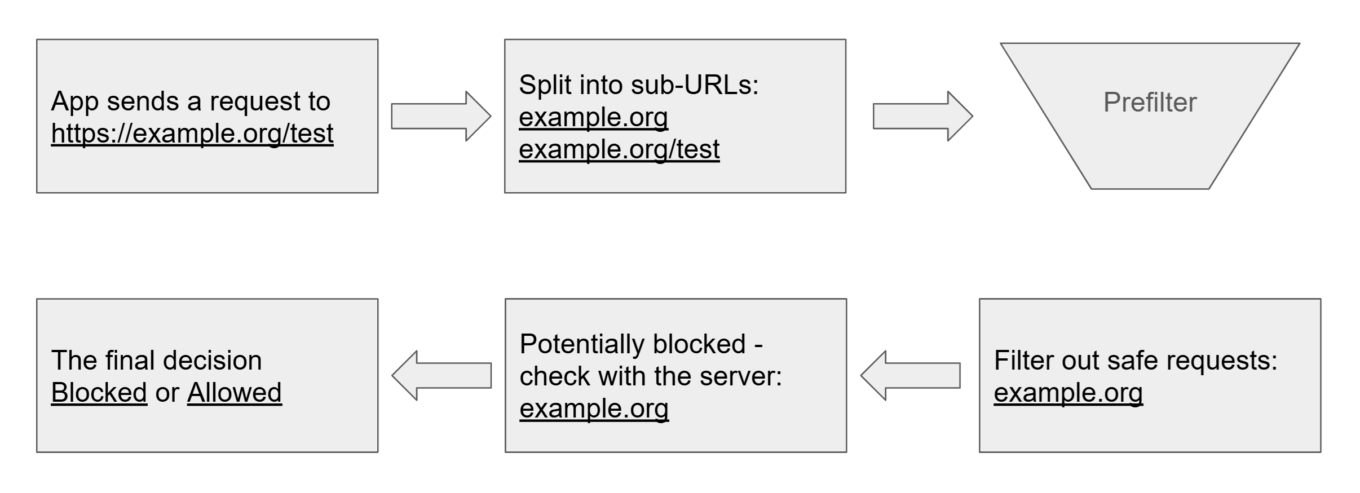

Let’s look at what happens when an app wants to send a request to https://example.org/test:

Apple’s URL filter high-level overview — Filtering

- The system splits the URL into sub-URLs.

- These are checked against a local prefilter to quickly decide which URLs can be classified as safe.

- The remaining are sent to your remote server for further verification.

- Based on the server’s response, the system either blocks or allows the request.

Now, it’s easy to see how a naïve implementation of this could turn into a privacy nightmare. To address this, Apple introduced several clever design decisions that aim to preserve user privacy while still enabling effective filtering.

The entire URL filter API is built on top of several modern privacy technologies.

- First, there’s Privacy Pass, which is used for user authentication.

- Next, there’s the Private Information Retrieval, or PIR service — used for server lookups. It’s accompanied by a Bloom filter, which acts as a local prefilter.

- And finally, there’s Oblivious HTTP.

All of these technologies are quite new and cutting-edge — so it’s fascinating to see Apple not only adopting them but integrating them into a real-world system like this. Let’s take a closer look at each of these components and how they work together.

Privacy Pass

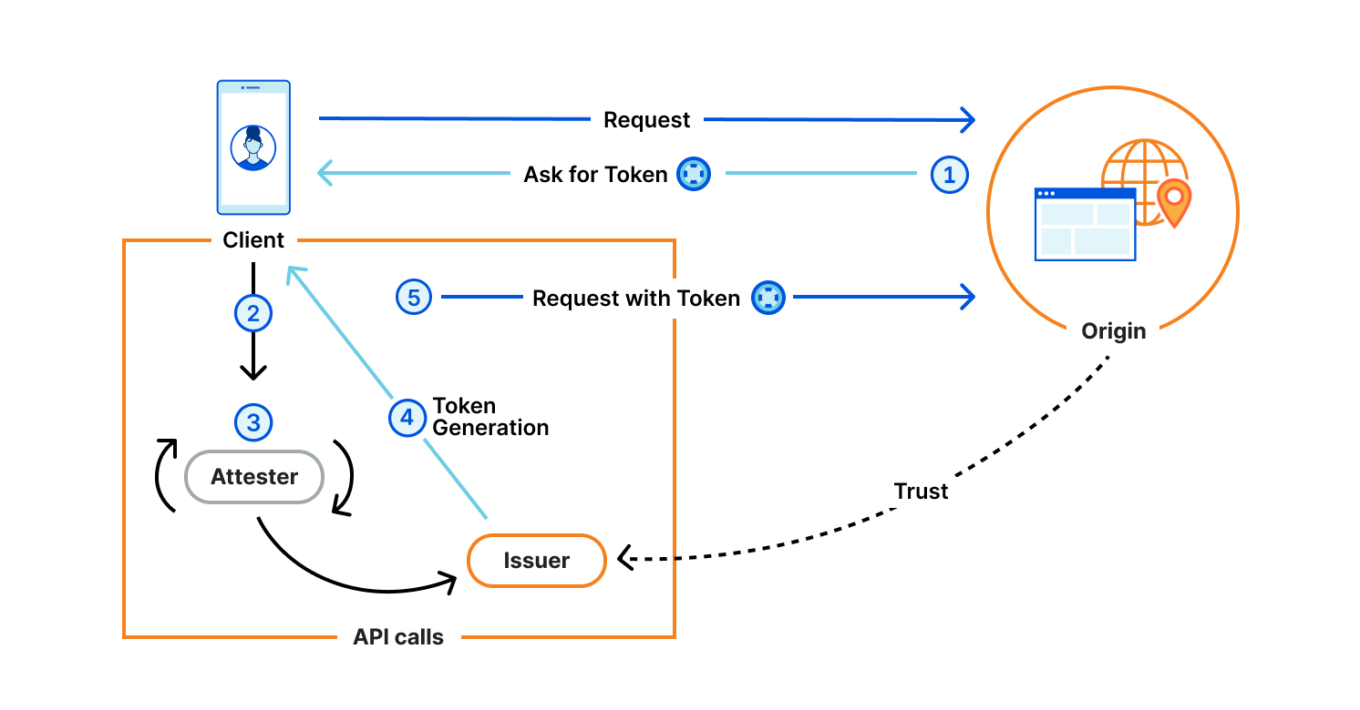

The first component is Privacy Pass. It is a modern, privacy-preserving authentication system. It lets clients obtain anonymous tokens that prove legitimacy without revealing identity or behavior.

Privacy Pass flow diagram. Source: Cloudflare Blog

As shown in the diagram:

- When a client sends a request to the Origin server, it can ask for a valid token.

- The client contacts an Attester to confirm its eligibility; if approved, an Issuer provides a Privacy Pass token.

- The client sends the token to the Origin, which verifies it with the Issuer’s public keys and accepts the request.

The core privacy idea is separation of roles: if the Origin and Issuer remain independent, authentication stays anonymous — the server knows the token is valid but not who the user is. That’s how Privacy Pass works in theory — but let’s look at how Apple actually uses it in their system.

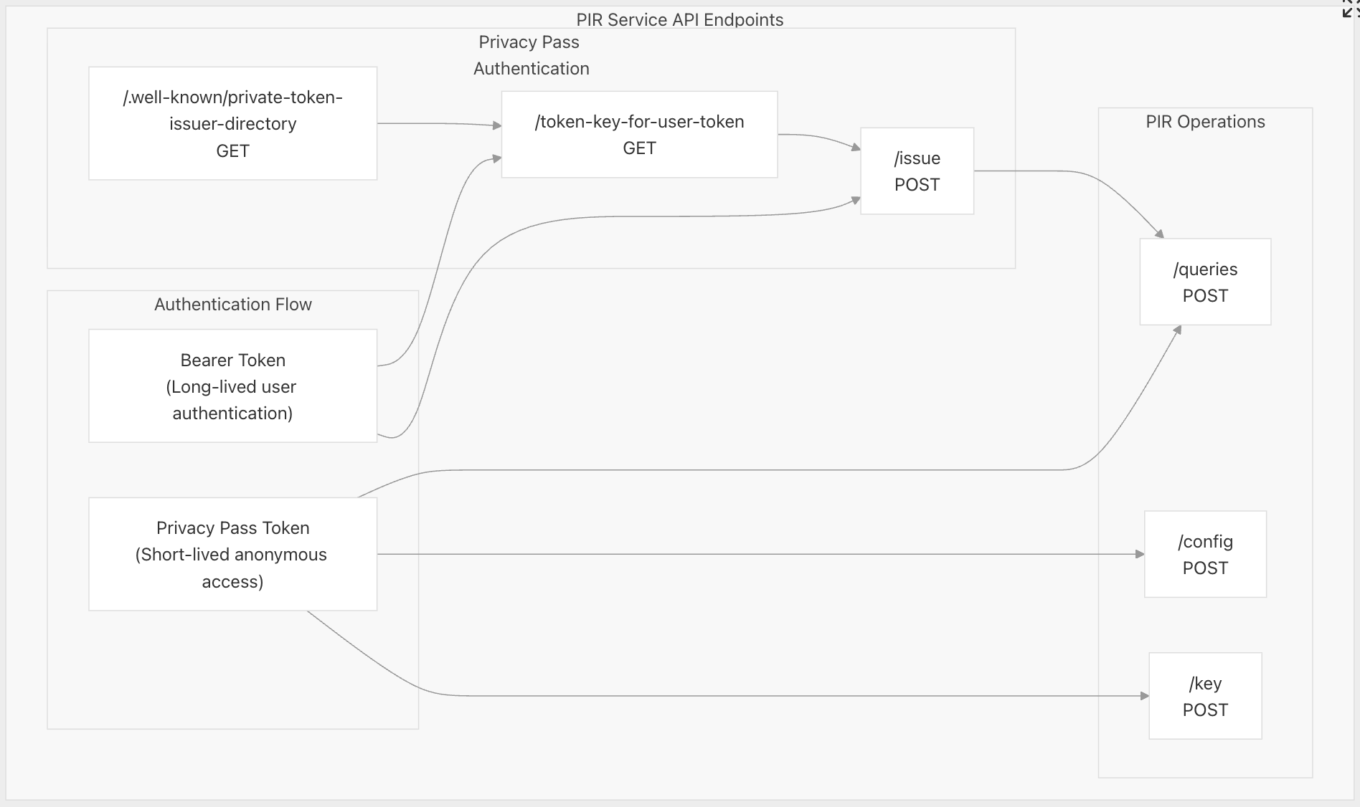

Privacy Pass — Apple’s PIR

- The client first authenticates using a persistent ID (such as user account) to get short-lived Privacy Pass tokens.

- Each PIR request redeems one of these tokens, proving legitimacy.

Looks similar to the original idea. But here’s the key point — unlike the ideal Privacy Pass design, both the Issuer and the Origin (the PIR service) in Apple’s system belong to the same entity, to the developer. Since the developer controls both, tokens can potentially be linked to users — so true anonymity depends entirely on the developer’s implementation. Now let’s focus more closely on PIR, or Private Information Retrieval.

Private Information Retrieval (PIR)

In simple terms, PIR is a family of cryptographic protocols that allow a client to retrieve data from a server without the server learning which specific item was requested. The idea isn’t new — it’s been explored since the 1990s. The oldest example of a PIR-like system in wide use is Google SafeBrowsing, introduced 20 years ago. It follows a similar principle, though without the heavy cryptography.

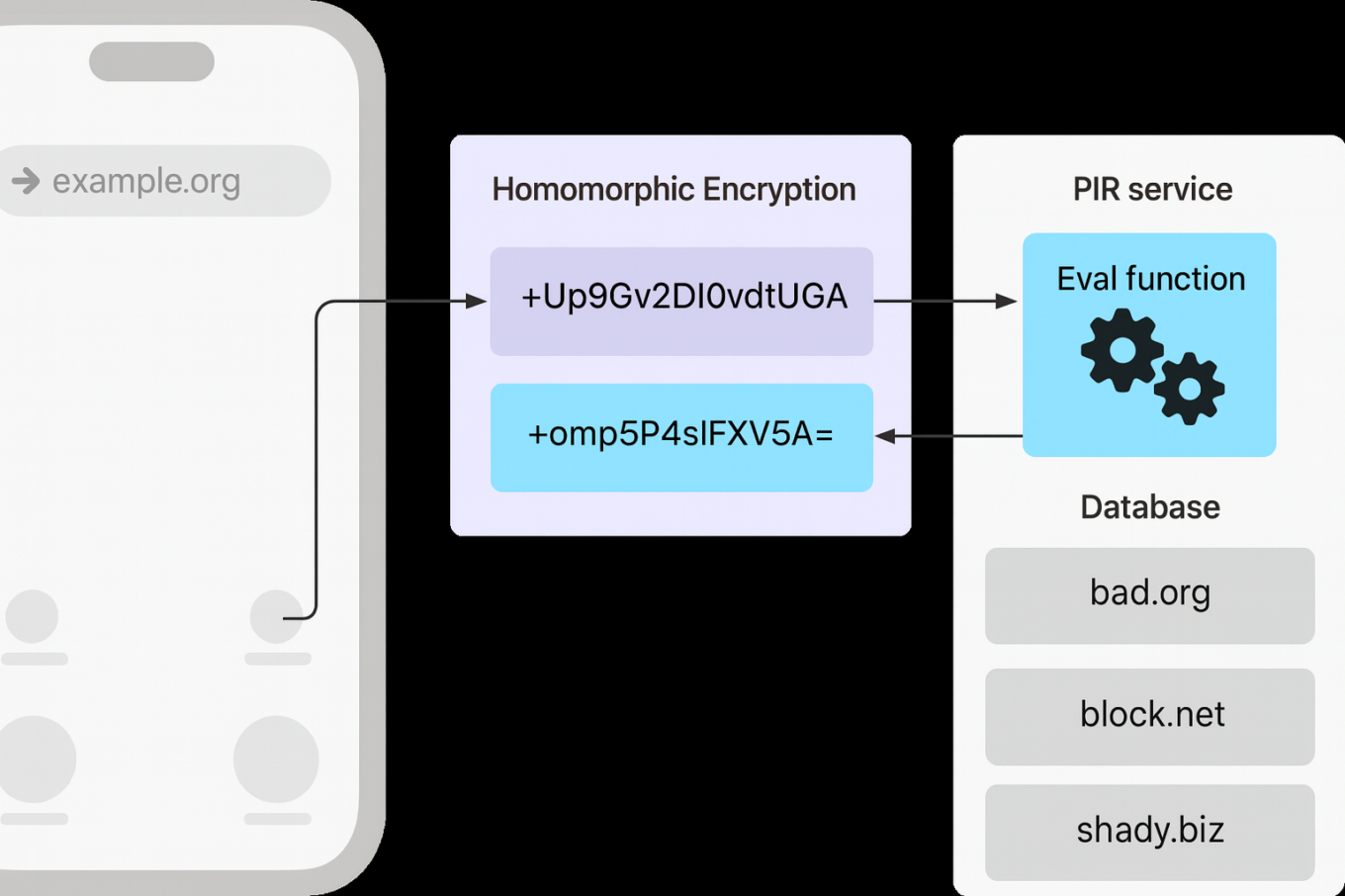

Apple’s implementation of Private Information Retrieval is a much more sophisticated system — a real, cryptographically private design. Here’s a high-level overview of how it works:

Apple’s implementation of PIR

- The server prepares a database — essentially a hash table — where each entry is encrypted and indexed.

- It then publishes a configuration describing how clients should interact with the service: hash table structure, encryption parameters, and other metadata.

- When a client wants to check a specific URL, it determines the corresponding index in that hash table.

- The client then creates a query saying “I want item X”, but the query is encrypted, so the server cannot tell what item X actually refers to.

- The server evaluates this encrypted query using homomorphic encryption, producing an encrypted response that includes several possible entries.

- The client decrypts the response locally and checks whether X is among those results.

- If X is found, the request is flagged as blocked.

So as you can see, this looks like a truly private information retrieval and the goal seems to be reached.

But let’s talk about performance. Apple’s PIR system is heavy on resources:

- Each query can be around 30 KB, which is quite large for a single API request

- A single lookup may take over 100 milliseconds, even under ideal conditions

And, as you’d expect, the larger the database, the slower each lookup operation becomes. To solve this problem, Apple’s PIR API allows sharding — splitting the main database into smaller parts. The server defines several shards; when checking a URL, the client computes its shard number using a function and includes it in the request. This speeds up queries but introduces a potential privacy leak: given enough shards, a shard might correspond to a single URL, revealing what the user is checking.

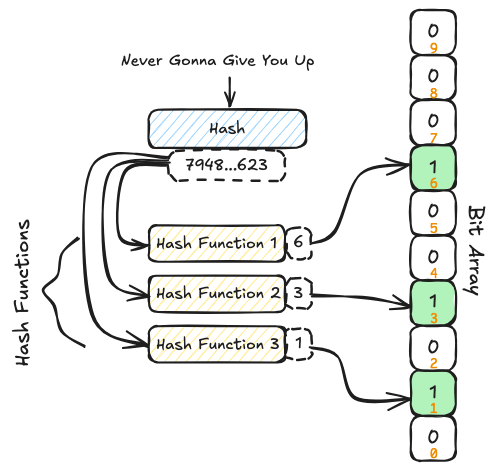

Can this risk be mitigated? Yes, I think so, Apple could mitigate this by enforcing a minimum shard size or a maximum shard count, and I hope they’ll consider doing that. But even sharding isn’t enough if the client has to send every single URL to the server. So Apple added another optimization step — a prefilter, which is basically a Bloom filter.

Bloom filter diagram. Source: bytedrum.com

I won’t go too deep into how Bloom filters work, but here’s what you need to know:

- They’re very fast and space-efficient

- A Bloom filter is designed to answer one simple question: “Is this URL in the dataset?”

- Possible answers are:

- Definitely not

- Possibly yes (meaning it might be in the blocklist, so we should double-check it using PIR)

The result is that most lookups never leave the device.

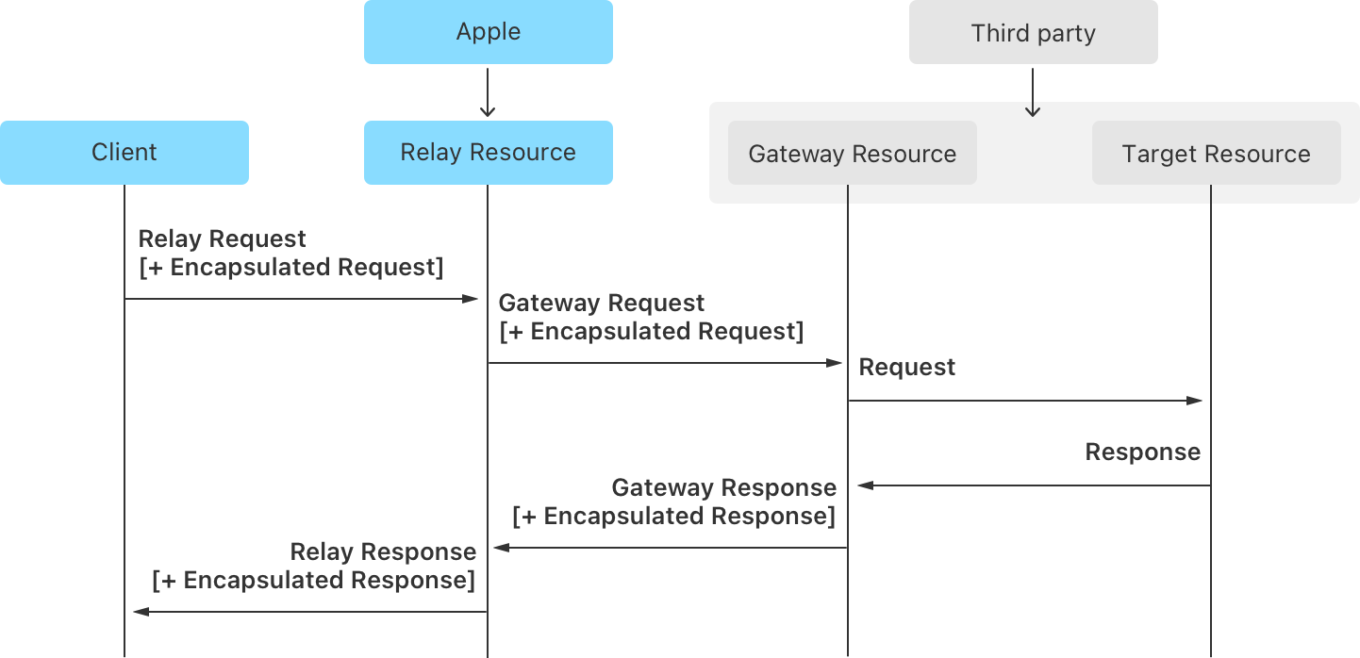

Oblivious HTTP

The last component of the URL filter API is Oblivious HTTP. To recap, Privacy Pass ensures anonymous authentication, PIR hides the query, and OHTTP removes the final identifier — the user’s IP address. OHTTP separates the client from the server using four parties:

- Client (user’s device)

- Relay (Apple)

- Gateway (developer)

- Target (final server, PIR or Privacy Pass)

Oblivious HTTP in Apple’s PIR

The client encrypts the request for the Gateway and sends it via the Relay, which just forwards it. The Gateway decrypts and processes it, encrypts the response, and sends it back through the Relay to the client. The idea is that the Relay knows who the user is but not what they send; the Gateway knows the request but not the user.

But even if you’ve managed to get everything working, there’s one last step — Apple’s review process. Before your app can use the new API, both your PIR service and your Oblivious HTTP gateway need to be reviewed and approved by Apple. Be prepared: the review can take quite some time, so plan ahead if you’re building around this API.

Summary

So how good is Apple’s URL filter? In the first chapter I presented a list of properties that an ideal system-wide filtering solution would display. Now, let’s revisit that list and see how Apple’s new URL filtering API measures up against those expectations.

✅ Full URL filtering

Check, no questions here.

🚫 Broad filtering capabilities

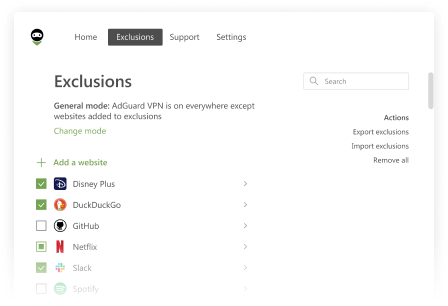

Unfortunately, this one doesn’t pass the test. Apple’s system lets you block requests, and that’s about it. There are also several important limitations on top of that:

- You can’t unblock individual domains yourself — it’s all or nothing. Either the entire blocklist is active, or it’s completely disabled.

- You can’t switch between multiple blocklists. Each app can only provide a single list.

Now, there are some theoretical workarounds — but those approaches are more like hacks than proper solutions.

✅ Support for huge blocklists

This one gets a clear check mark. The API was designed with massive blocklists in mind right from the start.

✅ Quick blocklist updates

Here, Apple also gets a check mark. The API supports automatic updates, and the minimum update interval is 45 minutes, which is actually quite good.

❔ Private by design

Now, this next point is a bit more complicated. For me, “private by design” means that when an app uses this API, the user remains completely anonymous, and there’s no possible way for the developer to learn who they are. And while that’s clearly Apple’s goal — the whole architecture is built around preserving user privacy — in practice, I can see a few loopholes that a developer could exploit to re-identify users or track their activity. Hopefully, Apple will address these issues in future revisions and make the guarantees of anonymity really strong.

🚫 API provides feedback

So, does the API provide any feedback to the developer about how it’s actually working? No. None at all. The app has no way to know whether its URL filter has blocked something or even checked a particular URL. In other words, it’s a completely opaque box.

🚫 Debugging tools

Unfortunately, there are no built-in tools to help developers or filter maintainers understand what’s going on under the hood. And as you can imagine, troubleshooting a URL filter is a very, very difficult task.

✅✅✅ And finally, despite all the shortcomings we’ve discussed, I want to end on a positive note. This API is infinitely better than not having one at all. It’s a big step forward — the first real attempt by any operating system vendor to make system-wide filtering both secure and privacy-preserving. I’m genuinely grateful to Apple for taking this initiative and being the first to think seriously about this use case. It’s not perfect yet, but it’s a very promising start — and I’m excited to see how it evolves in the future.

I’d like to add that we came up with our own implementation of PIR and it is currently being reviewed by Apple (for over a month, in fact). I hope very much that it will successfully pass the review sooner rather than later and we’ll be able to add this functionality to AdGuard products.

If you decide to experiment with Apple’s PIR system, here are a few tools and resources that might help you get started:

- PIR service + Privacy Pass: Apple provides an example implementation of the PIR and Privacy Pass services. It’s not production-ready, but it’s a great reference to understand how all the components are supposed to work together

- Testing PIR and Privacy Pass: To make testing easier, I’ve built a small command-line tool that can simulate the PIR and Privacy Pass flow — it’s open-source and available on GitHub

- Bloom filter: Apple didn’t release any official code for building one, and their documentation on it was initially quite vague. So I created a Swift library that can generate Bloom filters fully compatible with Apple’s URL filtering API

- Oblivious HTTP gateway: For Oblivious HTTP, Cloudflare provides both a reference library and a ready-to-use server implementation

- GoCurl — testing Oblivious HTTP: And finally, if you need to test your OHTTP setup, you can use my long-term side project called GoCurl. It’s basically a Go-based reimplementation of curl, with extra features like built-in support for Oblivious HTTP