Cookie consent popups have numbed Europe to the very issue of consent. They might go away soon

Cookie consent popups have been plaguing users in Europe for what feels like an eternity. After appearing in response to landmark pro-privacy EU regulations: first the e-Privacy Directive of 2009 and later the GDPR in 2018, these banners spread through the EU-governed internet sphere like wildfire. The intent behind their introduction was straightforward: make the user’s choice obvious to the user. The banners were supposed to alert users that the website they are on wants to collect data about them that could potentially be used for tracking.

Cookies themselves are small files placed on the user’s device. Technically, they store bits of information that websites need to function or wish to remember: login states, language preferences, analytics identifiers, advertising IDs, and more. Essential cookies are those strictly required to make a site work, things like keeping your shopping cart intact, stabilizing page navigation, or remembering that you’re logged in. Non-essential cookies, by contrast, are tied to analytics, personalization, and especially targeted advertising. These often involve sharing data with third parties and enabling cross-site tracking, essentially, the infrastructure of online surveillance.

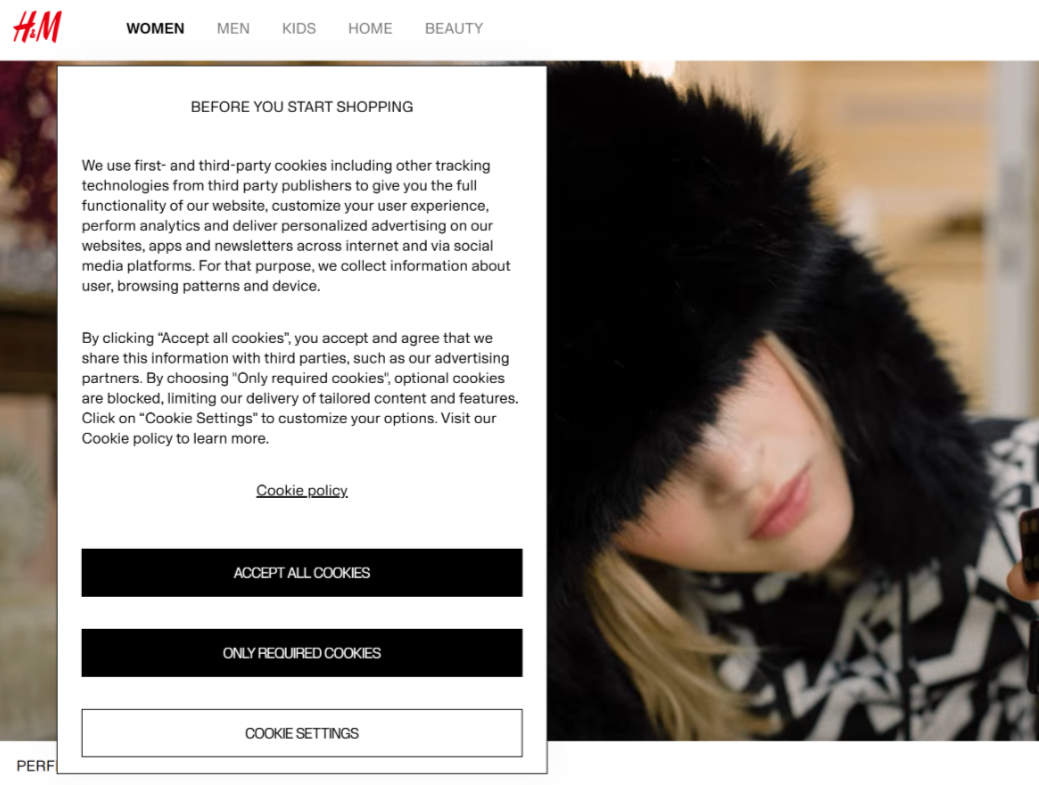

Usually, users are presented with a choice: accept all cookies, reject non-essential cookies, or customize their preferences by trudging through an often labyrinthine “cookie settings” menu.

While in theory this approach should have supported more privacy and more user agency, which are both unquestionably good goals, in reality it created so much noise that the banners became a form of sort of digital buzzing in the background, like a persistent fly you want to swat away as fast as possible. Even worse, users have grown desensitized to them. What was meant to be a meaningful prompt turned into a blind spot, a background irritant to be cleared away. The act of clicking on any option has turned into a mindless, automatic gesture, and, more often than not, users tend to instinctively choose the first one, which is almost always “Accept all cookies”. Instead of introducing genuine privacy protection, the system presents an underwhelming choice: an illusion of consent wrapped in a mandatory user interface chore.

The ubiquity of cookie banners has given rise to a phenomenon now commonly referred to as cookie banner fatigue. Turning a blind eye to the very thorn lodged in its own eye can only work for so long, and the European Commission seems to have reached that limit. In its new Digital Omnibus Regulation Proposal, published on November 19, the Commission finally decided to ease the burden by introducing new rules for cookie consent forms and potentially moving them completely away into the browser.

What the Commission wants to change

The European Commission’s new Digital Omnibus Bill steps in with what feels like an overdue reality check. After years of pretending the cookie-banner mess would somehow sort itself out, Brussels now appears ready to intervene and strip away some of the performative theatrics around “consent.”

To begin with, the Commission wants to redesign how consent is asked in the first place. Websites would have to offer a genuine one-click choice: yes or no, which apparently would lower the cognitive load. And crucially, once a user makes that choice, the site must respect it for at least six months. It’s a direct attempt to stop the psychological grind we’ve all been subjected to, namely the endless questions if we really want to accept those cookies or not.

Next, the proposal shifts part of the burden away from individual websites and into the browser itself. In the future, users should be able to set their privacy preferences centrally, this way they decide what types of cookies they’re comfortable with. Websites will have to honour those settings automatically. If implemented, this could finally break the cycle of being asked the same question hundreds of times across sites that all pretend they’ve never heard your answer before.

The Commission also draws a line between cookies that meaningfully affect privacy and those that don’t. “Harmless”, first-party cookies used only for basic functions or simple audience counts would no longer require a popup at all. In theory, this should cut down the sea of banners that serve no purpose other than helping companies to avoid steep fines for not implementing them.

Today’s proposal modernises the ‘cookies rules’, with the same strong protections for devices, allowing citizens to decide what cookies are placed on their connected devices (e.g. phones or computers) and what happens to their data. The new rules give real choices to users, with simplified design and effective design requirements for asking for consent or for allowing users to refuse it. They also prepare the ground for technological solutions that will bring further simplification and central controls for users.

The change in rules is meant to benefit not only users but also businesses, which the European Commission predicts could collectively save more than €800 million a year.

What does it all mean

If rolled out across the EU, the new cookie-popup rules promise to strip away much of the visual clutter users have been forced to wade through for years, replacing it with a more straightforward, binary choice: yes or no. The real transformation, however, would come with the next step, that is with allowing users to set their cookie preferences directly in the browser. That shift would mark a genuinely meaningful move toward stronger, more stable privacy control. Even a simple “yes” or “no” on every website adds up and still feeds into the same old popup fatigue. But if that decision moves into the browser and websites have to respect it for at least six months the endless stream of prompts finally eases off.

Essentially, what the EU aims to achieve with a new set of rules have been successfully handled by ad blockers. The notion that cookie consent popups are indeed a source of irritation for users has been an open secret, forcing them to enable filters that block them.

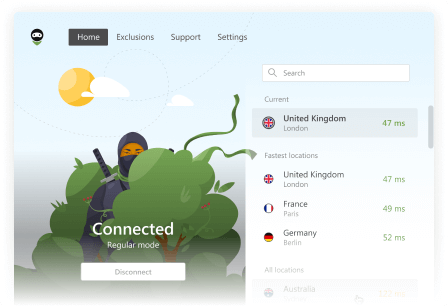

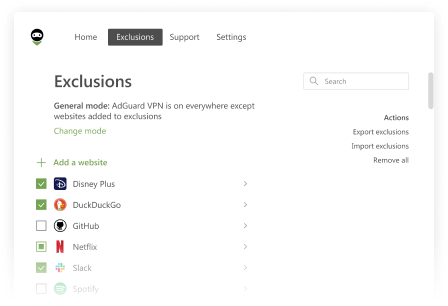

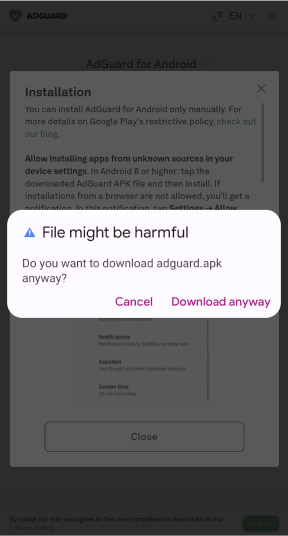

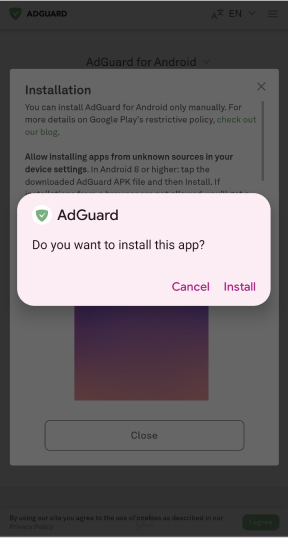

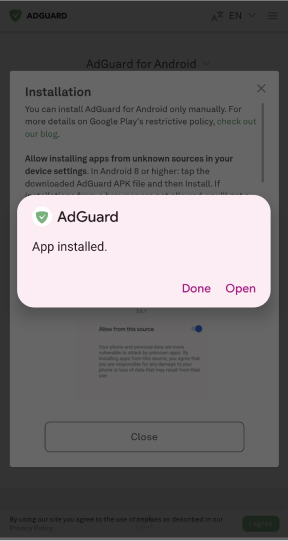

For example, AdGuard’s filters can block most cookie popups in real time, whether you’re using our browser extensions or standalone apps. You can hide annoying consent banners with the Cookie Notices filter or block tracking and advertising cookies selectively with the Tracking Protection filter, keeping your browsing smoother without breaking website functionality.

For more on the types of cookies, such as first-party, third-party cookies used for tracking and advertising, and harmful cookies that invade privacy, and how to block them effectively using tools like AdGuard’s Self-destruction of cookies and Tracking Protection filters, read this guide.

The European non-profit organization NOYB (None of Your Business), which specializes in defending privacy rights and challenging unlawful data practices across Europe, has long been critical of the widespread inefficiency of cookie consent mechanisms. In its analysis of the proposed cookie clause in the Digital Omnibus Bill, NOYB highlights it as a potentially positive step forward for companies not engaged in pervasive tracking practices.

As NOYB points out, “Most websites do not engage in online advertisement or tracking, but need a consent banner to be able to run (anonymous) statistics. Making this type of processing generally legal should, in theory, remove cookie banners from most “normal” websites in Europe.”

However, NOYB also rightly cautions that “other deceptive designs are not mentioned and some of the pain of cookie banners may just move to patterns that are not about the existence of a reject button.” We fully agree: simply removing banners does not automatically solve the broader problem of manipulative consent mechanisms. This is a real danger that users and regulators alike must remain aware of.