The tide is turning: Facebook and Instagram to have paid ad-free options

Five years after then Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg hinted at a paid option to opt out of targeted ads, this feature is said to be finally coming to Facebook and Instagram users in the EU.

You may ask: what took Meta so long? Well, it’s not exactly that the company has been itching to introduce this option — rather, it’s been compelled to.

According to a report by the Wall Street Journal, Meta is considering rolling out paid ad-free versions of Facebook and Instagram in the EU primarily to appease the bloc’s increasingly hawkish regulators. The latter have been out for big tech’s blood, including Meta’s, since 2018, when the EU’s landmark privacy law, GDPR, came into effect. The law gave EU users more power over how their personal information is used by tech giants. In an ideal world it would have required tech firms to receive users’ consent in every instance where they collect their data to make money from it by default. But reality isn’t that simple, so instead it’s been a slow push by regulators as Meta and co. have tried to wiggle their way out of this cat’s cradle. Below is a brief recap of how exactly Meta had tried to do so.

Meta wrestles with regulators…

Just before GDPR took effect on May 25, 2018, Meta made a sneaky move and switched its basis for processing most of user data from “user consent” to “contractual necessity.” In doing so, Meta all but declared that showing ads based on users’ personal web browsing history was essential to fulfilling its contact with them. In practice, this meant that if you wanted to use Instagram or Facebook, you had no choice but to submit to Meta’s data collection practices. This went against the spirit of GDPR, which was supposed to prevent companies from making the processing of personal data a condition for using their service, unless that data was absolutely necessary to provide that service. And, since Facebook’s main product, at least on paper, has never been mining people’s data for ads, but social networking, the “contractual necessity” excuse did not make much sense from the start. So, before long, privacy activist Max Schrems filed a complaint against Meta for using what he called a “forced consent” approach aimed at arm-twisting users of their personal data.

“It’s simple: Anything strictly necessary for a service does not need consent boxes anymore. For everything else users must have a real choice to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’,” Schrems wrote back in 2018.

The following year Germany’s competition watchdog, Bundeskartellamt, attempted to put a stop to Meta’s data hoarding and pooling practices. It banned Meta from combining data about users that it gleaned from its plethora of services (WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook) without their consent. Separately, the watchdog also prevented Meta from harvesting data about users from third-party websites via “Like” buttons and invisible embeddable codes called “tracking pixels” without consent. That decision threatened to sink Meta’s entire ad sales model if regulators abroad got a whiff of it, so Mark Zuckerberg’s company promptly challenged the ruling, and a lengthy court battle ensued.

While this legal battle was being waged, the EU’s data protection watchdog was not sitting idly by. In January 2023, Ireland’s Data Protection Commission fined Meta $414 million for lacking a proper legal basis to process EU users’ data for personalized advertising. The watchdog found that Meta “was not entitled to rely on the “contract” legal basis in connection with the delivery of behavioral advertising as part of its Facebook and Instagram services,” and that by continuing to claim “contractual necessity” to process user data for advertising, it was in breach of the GDPR.

That decision set a lot of wheels in motion, prompting Meta to change its legal basis for processing data once again, this time to “legitimate interests.” This one did not hold out for long either, though. Six months after that, the European Union’s highest court — the European Court of Justice — delivered Meta arguably the most painful and most devastating blow yet. Ruling in the drawn-out legal saga between Bundeskartellamt and Meta on July 4, 2023, the court sided with Germany’s competition authority. That decision gave Bundeskatrtellamt the all-clear to block Meta from combining data that it collected about users by tracking them across its many platforms and third-party websites. “The mere fact that a user visits websites or apps that may reveal [sensitive data] does not in any way mean that the user manifestly makes public his or her data,” the court said. But perhaps the most important part of the ruling was that Meta could no longer claim “legitimate interest” to collect people’s data to target them with ads unless it has their consent.

…and loses

Emboldened by the EU privacy watchdog’s ruling, Norway’s data protection regulator was the first to stick the decision in Meta’s face. On July 17, it issued a temporary ban on behavioral advertising on Instagram and Facebook and slapped Meta with hefty fines for profiling users without consent. You can read more about this in our previous article.

Meta, backed into a corner and facing more legal challenges to its behavioral advertising business from the incoming EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), had no choice but to give in.

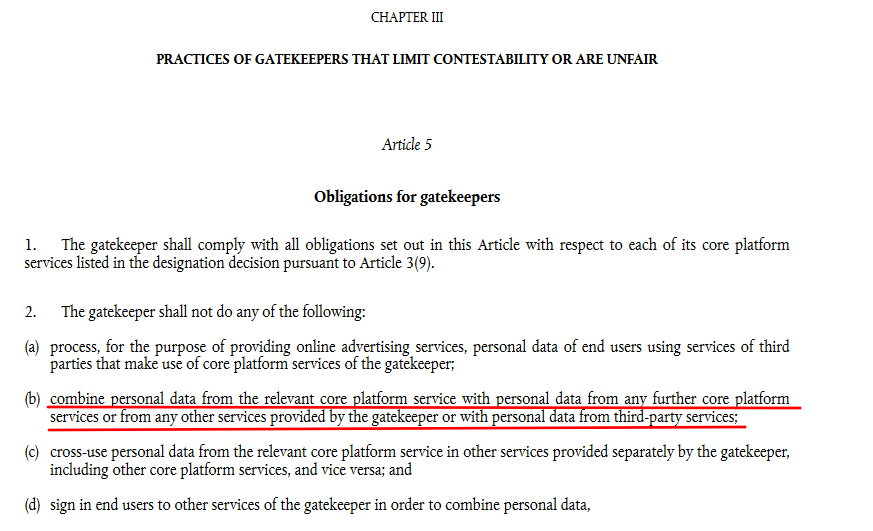

EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) expressly prohibits data combination and cross-use of personal data. It is to fully come into force by 2024.

On August 1, the company announced it would be changing the legal basis for processing user data from “legitimate interests” to “consent,” thus coming a full circle. If we take everything what Meta says at face value, that would mean that Europeans are finally getting a chance to say no to being tracked and profiled for ads. And if the Journal’s report is true, the next step for Meta in its attempt to convince the EU regulators that Instagram and Facebook users do have a choice when it comes to their personal data is to introduce a completely ad-free option. That option presumably would involve even less tracking — at least one would hope so.

Is Meta’s rumored paid offering a smokescreen or a genuine U-turn?

However, as much as we want, it’s impossible to take news about Meta’s rumored paid offering without a pinch of salt. Too little is known about the reported ad-free option in the EU to make any definitive conclusions. Citing anonymous sources, the Journal reported that Meta would be offering both ad-supported and ad-free versions of their services in the EU. So far, there is no information as to how much Meta plans to charge for its ad-free plans, and when it wants to roll them out.

But it would certainly be interesting to see the numbers. If anything, they will reveal how much Meta earns by mining an individual user’s data. That is, if we assume that a subscription fee is designed to compensate for the loss of ad revenue. However, Meta’s reluctance to introduce a paid ad-free option in the past might suggest that ad revenue would be very hard, if not impossible, to replace through subscriptions. And it may be so that Meta does not really hope to do this, but rather gives users an ad-free option as a token gesture in response to privacy concerns.

Ad tracking has always been at the heart of Facebook’s, then Meta’s business model, and it’s hardly conceivable that the company will be making a complete U-turn. The company’s history till this day has been about gaming the system and exploiting loopholes when someone, be it Apple or regulators, tried to limit its tracking operation. Back in 2018, when Meta was still called Facebook, its global deputy chief privacy officer Stephen Deadman likened Facebook ads to wheels that enable a car drive, with the car being Facebook itself. “There’s no point in buying a car and then saying you want it without the wheels. You can choose different kinds of wheels, but you need wheels,” he said.

Since nothing suggests that Meta will also consider introducing ad-free options outside of the EU, we can safely assume that it does not see it as a good business strategy. Meta’s ad business is going through a renaissance right now, and with Europe being the second most profitable region for Meta after North America (accounting for about 10% of Meta’s ad business), it was probably hoping to rake in some moneys from European marketers. Instead, it has to wrestle with privacy regulators and cull its own tracking operation under the threat of mammoth fines.

Will, however, the threat of regulatory punishment be enough of a deterrent for Meta to stop milking users for data without their knowledge is still a question that needs to be answered. And given Meta’s penchant for dark patterns, it’s probably not the last time we’ve heard of its sparring with regulators, even though it may seem that the latter has won for now.