Hey Google, we've fixed it for you: AdGuard will block Topics to make Google Privacy Sandbox truly private

- Privacy Sandbox is an assortment of technologies proposed by Google to make advertising more privacy-conscious

- Privacy Sandbox promises privacy protection, but the concept fails through due to one faulty element — Google Topics

- Topics won’t stop tech giants from collecting vast amounts of user data

- Topics may make it harder for a single website in a vacuum to identify an individual user, but not for Big Tech

- Topics will cement Google’s ad monopoly

- Topics is one bad apple that spoils the whole barrel, therefore AdGuard is blocking it

With Google launching early testing of its Privacy Sandbox initiative for Chrome and on Android, it’s high time we at AdGuard voiced our position on it. Better late than never. Without going into much detail (you’re welcome to read about each of the Privacy Sandbox mechanisms further in the article), we can say that we’ve developed a special dislike for one proposal in particular — the Google Topics API.

We believe that Topics is a deeply flawed technology that hardly prevents Big Tech from continuing to collect vast swathes of user data. If anything, it further strengthens Google’s grip on the booming ad market. Therefore, we will be blocking this API from now on.

In a nutshell, Topics promises to protect users from fingerprinting by giving third parties access to user interests in such a way so that they won’t be able to identify the individual user. On paper. In reality, they will still be able to do this, as we will show below.

As for the Privacy Sandbox initiative as a whole, we will make sure it lives up to its name by eliminating any and all backdoors that may compromise user privacy.

The long-in-the-making privacy initiative was rolled out for testing by Google last month. First developers are invited to set trial tests of its key proposals, including Topics, which is designed to replace third-party cookies and has turned out to be the most controversial of all.

So far, only “a limited number of Chrome Beta users” are be able to take part in an origin trial of the mechanisms that are part of the Privacy Sandbox for web. Those include the above mentioned Topics, FLEDGE and Attribution Reporting.

Google also unveiled the first developer preview for the Privacy Sandbox on Android, a sister initiative inherently similar to that for Chrome. Developers can take a glimpse at how some of the technologies (that time, it is SDK Runtime and Topics) work on Android.

Let’s take a closer look at the Privacy Sandbox for web (to be used in Chrome) and the Privacy Sandbox on Android to see what exactly developers will be getting themselves into if they give the technology a try and what ordinary users should expect from it.

Privacy Sandbox for web

DNS-over-HTTPS. In reality, when you enter a website's address into the Chrome's (or any other browser's) address bar, it doesn't really know where to go. The web doesn't use humanlike words like google.com, facebook.com, etc. Instead, a so-called IP address is used. And when you try to connect to a website, your browser requests this website's IP address from a DNS server. This information exchange used to involve an open protocol, so, despite HTTPS and other security measures, it was still possible to find out which websites you visit. This already gives away some information about you. DNS-over-HTTPS plugs this hole by encrypting the dialog between your browser and the DNS server.

Gnatcatcher — a technology that hides your real IP address. It somewhat resembles VPN, in the sense that the main goal of this technology is to make it impossible to determine your real IP address, and therefore your location.

Privacy Budget — a bundle of measures to reduce the amount of data about your system that websites can obtain. Obviously, the less data they have, the harder it is to identify you and discern from the crowd.

FLEDGE — is a specialized audience targeting mechanism. It can be used to show ads: for instance, when you add items to a cart in an app, leave, and another app shows you the ad of that store reminding you that you forgot to complete your order. Nowadays, it is done with the help of "audience" lists. A list can include, for instance, a user's email address and often other identification information. Companies that post ads can share these lists with each other, and also with third parties. What's important, the ad to show is chosen right in the browser, without any information leaving the user's computer.

But indisputably, the most controversial and topical (pun intended) initiative of them all is Google topics.

What is Google topics?

Not so long ago Google introduced a new technology called topics. It was designed to replace 3rd party cookies and, as a result, cross-site targeting and fingerprinting. But does it really? Let's see what lays under the hood, but first we'll need to figure out what they want to replace.

How is it implemented now?

Today, when accessing a website, your device receives a small chunk of data from the server and stores it locally. The data chunk may be used for storing authentication state, user's visits statistics, personal preferences, user settings, or tracking user's session state. This technology is called cookies, and we've all grown accustomed to it (remember all those annoying "I accept cookies" popups?). It means that when you visit a website, let's say example.com, you receive cookies from this site. The website writes in the cookie files any information about the user that they'd like. Then you leave the site and come back again some time later — this file is then sent back to the site, and thus example.com is able to identify you. Cookie files may contain any type of information like operating system, browser type and version, which kind of content or selling products you looked for, and so on.

But that's not all. If a website contains any ad banners or other types of advertising with another domain name (for example, ad.sirbuymepls.com), you will receive a third-party file belonging to that domain. It's called third-party cookies. Therefore, 3rd-party cookies are cookies sent by another website rather than the site you are currently visiting.

Some advertisers (a lot of them, to be honest) use these types of cookies to track your visits to other websites. This is called cross-site tracking. And aside from information directly related to the products they sell that you would expect them to track, they often may try to determine other, less obvious data points about you, like your gender, race, religious and political views. It goes without saying that the information collected about you is often sold and bought — this is a serious breach of user privacy that results in the misuse of user data.

Is there any work being done in this direction?

Yes, absolutely! Today many browsers — such as Safari, Firefox, Brave, Tor — already have strong built-in protection tools. For instance, Safari uses WebKit engine that employs the Intelligent Tracking Prevention mechanism. Or take Brave that stores such personal information in isolated (sectioned) storages and deletes it as soon as you close the website, therefore preventing third parties from getting this info.

You can't talk about privacy-oriented browsers and not mention DuckDuckGo. The company that got famous for its privacy-first search engine has been working on its own browser for a while. You can bet that it will bite a chunk of the market share from other browsers. And DuckDuckGo are not the only ones who work in that direction.

Unfortunately, it's hard to evaluate how big of an impact all those factors have on users' privacy in general, especially since Chrome only plans to start locking third-party cookies.

But Google has its own way, right?

Indeed. Unlike Apple, which blocks 3rd-party cookies in Safari and uses a similar approach to applications, Google would really like to keep allowing targeted advertising. As many of you probably know, Google's parent company is Alphabet. How does Alphabet make money? Right, off advertising. And Google Chrome is the most popular browser in the world by far. Add two and two, and you'll realize that Alphabet has a direct interest here.

Observing how Meta is rapidly losing profit, audience, and capitalization, you would think that a good decision would be not to resist the trend of privacy protection, but to lead it.

Most likely, an open counteraction to this trend and the support of the current state of the ad market would make it worse for Google, so they have to take some steps in that direction. But they make a great effort to have the best of both worlds: to satisfy some of the users' privacy-related demands and to keep their commanding position on the ad market.

Like we've already said, Google Chrome has the biggest share among all the web browsers by far. And not only that, Chromium browser engine is used in a lot of other browsers, which means that Google has a near-monopoly on the development of web standards. An example: AMP technology still has got a wide spread despite having analogs among Chrome's competitors.

Having a monopolist in web technology is bad enough as it is, but having a monopolist that gets a lion's share of its profits from advertising is even worse. Despite all that, the first tentative steps that Google's been taking towards rejecting cookies were received extremely negatively. Many developers of web browsers rejected FLOC, Google's first attempt at substituting cookies. Google took that feedback into account, and now we have Google topics as its new iteration.

So, is topics any good?

Let's dig deeper into the matter to answer this question. With some help of open-source intelligence from facebook.com, we obtained data about 272 billion ad views for the US audience. Note: the research envelops 260 topics, which is less than 350 topics offered by Google, and far less than the possible number of cohorts. What did we get? The image below shows the most popular…

…and the least popular interests.

The columns reflect the minimal and the maximal audience coverage (millions of people), and the probability of any particular person being attributed to this interest. All interests were listed from the most to the least popular. The resulting distribution looks like this:

And this is the resulting data:

Despite Google's claims that 350 "coarse" topics will divide users into multiple subgroups, we see the opposite. Even more, if you take into account users' locations, you would only need a few relatively rare topics to exactly identify the user. And Google states that 350 is an approximate number, the real one can be upped to several thousand, thus narrowing the search even more.

At the same time, Google sort of offers a fingerprinting protection mechanism. This is how it is supposed to work: every week, a special app on the user's device selects five most popular topics, another random topic gets added to them, and the website you visit receives one of these six topics, again at random. Any website that you're visiting for the first time receives three topics for each of the past three weeks.

It's implied that the website can't collect any information aside from what the technology allows. And when you visit other websites, supposedly, they will get different topics, and this will prevent them from correlating the data and identifying you. This isn't how it's going to work at all. Google's scheme would only work for a single website in a vacuum. In real life, corporations own multiple services, and each of those services will receive its own piece of data. Smart people working for those corporations will easily find ways to correlate them.

The best example is, perhaps, Meta with its Facebook, Instagram, and Whatsapp. We already have three extremely popular services, each of them gets 1 topic per week, and you are free to correlate this information all you want. Now imagine accumulating these data points for weeks and months — building up a profile isn't that hard of a task at this point.

Google itself is just as good of an example. You can expect an average user to watch YouTube, listen to YouTube music, use Google maps, Google drive, Gmail, or any combination of those megapopular apps. Do you see where we're going? With a vast amount of services controlled by Google it will be able to receive an enormous amount of information about nearly any user. And we haven't even mentioned various SDKs for collecting metrics, which almost any website has nowadays. Who are the biggest vendors for those SDKs? Google and Meta.

Google has managed to kill two birds with one stone: walled smaller companies from getting user data and left practically infinite possibilities for itself. Considering how widespread Chrome and Chromium-based browsers are, this is a bulletproof plan to strengthen the company's position on the Adtech market.

Google may want us to see the new topics technology as an absolute good, but we now know that it is yet another shot at getting an ad monopoly.

Android Privacy Sandbox

A similar technology is going to be introduced for Android under the name of Android Privacy Sandbox. The only difference is that while in the case of the Privacy Sandbox for Web we were talking about websites, this time the focus is on the tracking of apps users are interacting with. Let's take a closer look at what Google offers:

SDK Runtime

Nowadays, there are plenty of SDKs (Software Development Kits) that facilitate the work of software developers, namely, by offering them a fixed toolkit consisting of various mechanisms and/or utilities that can be used in an app. Thus, SDK data can be reused in different applications, and developers do not need to reinvent the wheel all over again. Rather, they can take advantage of a readymade and tried-and-tested solution. Moreover, it allows developers to focus on the functionality of the product and dramatically decreases the time spent on the development itself, and hence, the cost of the product. The problem with the previously used SDKs was that they were part of the host app and were executed together with it in the same "sandbox" (environment, isolated from the main system and the other applications in this environment).

It also gave rise to some privacy concerns. For instance, if the app was granted access to contacts, location, calls and messages, files etc., SDKs would inherit all these permissions. This came with certain risks: since it was possible that developers would not always check SDK for any undeclared functionality, SDKs' vendors could have gained access to user data. It goes without saying that there were some unscrupulous libraries' vendors who were harvesting user data and selling it to enrich themselves. Google sees the proposed SDK Runtime as a solution to this problem. It all boils down to this: now SDK dependencies will operate in a separate sandbox, and won’t have access to the user data obtained by the app.

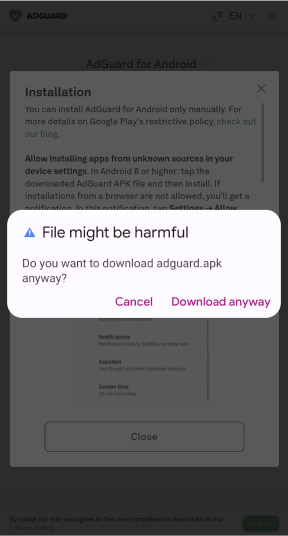

Moreover, Google is planning to implement the trusted SDK distribution model. Previously, developers used to download SDKs from several sources, running a risk of getting an SDK with embedded malware. Now there will be a specialized app store responsible for the distribution of SDKs. Since SDKs will no longer be part of an app, the app will now have specialized SDK data interfaces or, in other words, protocols to interact with SDKs' data.

Users will be able to upload SDKs from the trusted app store.

Thus, the number of attacks on the SDKs' supply chain data will decrease. We hope that this store would introduce a safety check similar to the one in Google Play Store. This will improve the situation with the viruses on Android. Moreover, third-party SDKs won't be able to harvest user data as they please any longer.

Android topics

Both in its name and in principle, Android topics are similar to topics for Chrome. However, there are some slight differences that we will go over now.

Since in this case the technology was developed for mobile, it will identify the mobile apps a user has interacted with rather than the websites they have visited. Overall, the scheme has not changed much. The 5 most popular topics for the week will still be determined. The sixth random topic is added as well — it makes this part of the algorithm identical to that of topics for Google Chrome.

The topic of the app will be defined based on the app’s name and its description. Google claims that different apps will receive different data from you, thus they won't be able to fingerprint you.

We have already touched on the flaws of this approach, but let's spell them out once again: Perhaps, a single app will have some troubles with obtaining user data, however, it won't become a problem for big corporations and companies that leverage a lot of apps. Probably you have Facebook, Whatsapp and Instagram installed on your phone. Maybe also Messenger? Each of these apps will be able to receive your topics, moreover, they will be doing it long-term and they will be accumulating data about you. Would Meta be able to cross-correlate all this data and figure out that it is about the same person? If it so wishes, it will not be difficult to do.

We've already gone over Google's services. All of them have mobile apps: Youtube, Google Play, YouTube Music, Gmail, Google Drive, gPhoto and many more apps are doing exactly that. Can you imagine the sheer scale of the data being collected? And we have not talked about the information that Android OS can gather yet.

It should be mentioned that there are also advertising SDKs that are part of the app. What's more — there can be several different SDKs in one app. Here we can see the distribution of popular SDKs among user devices.

SDK AdMob is owned by Google, and, as we can see from the image above, it is embedded in more than 90% of apps on Android! Just imagine how much data Google can collect if it is able to harvest information from 19 out of 20 apps on your device. This is a very lucrative piece of the cake. And while the proposed changes for Google Chrome have yet to come into effect and it's difficult to gauge their impact on the online advertising market, we can try to assess the looming changes for Android through the example of the new Apple privacy policy and universally-detested Meta.

Let us remind you: Apple has required all app developers to disclose what information they collect. This has prompted a sharp criticism from Meta, which tried to rally against these rules and even fight them in court. Ironically, after Meta complied with the policy, Messenger has turned out to be the app collecting the biggest share of user data among all the apps featured in AppStore.

Meta saw its profit, the bulk of which comes from advertising, drop in its quarterly report in February. Against the backdrop of this news and Meta’s failure to achieve planned objectives, the company lost almost $250 bn in market value. Tough measures taken by Apple are seriously undermining the advertising business. Meta has recently revealed it expects the changes to the Apple privacy policy to cost it some $10 bn in ad revenue this year.

Now it has become clear why Meta was so vocal against the new Apple policy. Moreover, Google had not updated some of its iOS apps for over a month after Apple made it mandatory for developers to disclose what data their apps collect.

Isn't it the ultimate nightmare for the companies that live off advertising? It's likely that Google has to follow into the same footsteps and force developers to disclose the data their apps are going to collect. It is doing so under public pressure and in order not to lag behind its main competitor.

As we can see, Google is trying to clamp down on fingerprinting, although its methods are quite soft, and are rather a smokescreen to cover the lack of action. There are no technical reasons that would have prevented the company from gathering information about users. Such reasons simply do not exist, as we have already mentioned.

FLEDGE for Android

We've already covered FLEDGE for web, and FLEDGE for Android works much in the same way. This mechanism is aimed at limiting the possibility of the misuse of personal data. One of the best examples.One of the best examples of a flagrant abuse of personal data is the infamous Target case. Based on what a schoolgirl looked at/bought on the internet, the company sent her coupons for baby clothes and diapers. The girl's parents were, of course, unaware of her predicament and were really surprised to receive the coupons in the mail. Nowadays, the abuse of this technology does not seem that insignificant, does it?

For its part, Google offers special algorithms that would generate such audience lists, which, consequently, would be stored locally on a user's device. The special algorithm would also select ads to show to the user. This is meant to ensure that the information does not fall into the hands of third parties.

Attribution reporting

This mechanism introduces changes to the conversion tracking. Advertisers want to know how users interact with their ads: for how long, how many interactions it takes for users to convert; the message they click before a conversion takes place, and other data in order to learn what attracts the audience, which ads generate most sales, at which moment users start to lose interest, and so forth. At present this information is tied to a user's unique ID and is being collected by various SDKs. We can only guess what happens with it afterwards. Google suggests, by analogy with the previous mechanisms, to measure and calculate everything on the devices themselves, to delete unique user IDs and send the data to the advertising vendor in an aggregate and encrypted form. The vendor won't be able to decrypt the data. It will have to register with the trusted service and hand over encrypted and aggregate reports that it has received to that service. The data would be decrypted and the legitimacy of the attribution would be verified in the trusted service as well.

In addition to that, the amount of information collected for triggers is limited (the number of bits available for event-level reports). For example, there will be only 3 bits available for click-through triggers, which won't allow advertisers to receive information about trigger time. Apart from that, restrictions will be imposed on the number of triggers, and the companies won't be able to register with the service several times and receive different data via several channels. Thus, the amount of collected information will be limited, and the scope available will be just enough to receive only the essential data about conversion.

Conclusion

We can see that the proposed Google technologies are still in need of a lot of work. Some of them, namely Runtime SDK, FLEDGE, and Attribution reporting appear to provide real value and make our lives a little bit more private.

The value of the other technologies, such as Google topics, is highly questionable: they drive small companies from the market, reinforcing the dominance of tech giants. Besides, these technologies do not solve the main problem: who said that it was OK to collect and share our interests without our permission?

We can be absolutely sure only about one thing: technology, algorithms, and infrastructure to execute these mechanisms are turning Google into an advertising monopoly for Android and Chrome. The company is not bound by any technical constraints when collecting information thanks to its extensive system of applications, services and SDKs. In the war between AdTech and user privacy, Google won.