Your smartphone eavesdrops on your TV — and sometimes directly talks to it

There are more than 1000 game apps in Google Play that include software for detecting TV ads. Once installed, an app uses a smartphone’s microphone to identify audio signals in TV ads and shows, even when the game is not played, and the phone lies still in the owner’s pocket.

The software is provided by a company named Alphonso, reports the New York Times. But it is more than likely that Alphonso is not the only startup to develop a solution of this kind. Advertisers value the information about ad performance very highly, and there are a lot of ad tech companies trying to provide them with data on ad delivery and efficiency. Some "competitors" of Alphonso have been mentioned in the NYT piece.

This is not exactly the case we’ve covered in our blog some time ago when we talked about whether or not Facebook and Instagram listen to your offline conversations in order to target ads based on the topics you discuss.

Facebook, by the way, denies eavesdropping on people’s chats offline, but the company actually had a feature called “Identify TV and Music” in their app since 2014. It could listen to the ambient noise through a microphone and define what music a user listens or what TV show they watch while writing a status update.

Detecting ads in the ambient noise around a phone is much easier technically, than analyzing conversations. Advertisers can embed a specific sound identifier in their videos, unaudible for people and easily caught by a device. This can be done for a variety of purposes, including cross-device tracking (joining information about your usage of several gadgets) and cross-device targeting (you watch a show on TV and see ads related to it on your phone).

The ability of gadgets to define sounds inaudible for a human ear puts users at risk, researchers found. They played voice commands in ultrasound, and the commands were recognized and executed by popular voice assistants (Siri, Cortana, Alexa, Google Now and others). Hackers can exploit this possibility for malicious purposes: subscribe a person to a paid service, install an app that would steal information, and so on.

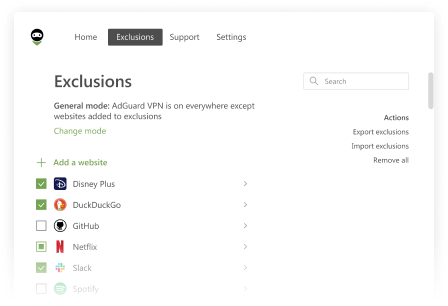

If you don’t want advertisers to know what sound your TV set plays, you should pay attention to the permissions you give to the newly installed mobile apps. People often give all the requested permissions without a second thought. Do you really think a weather app need access to camera or microphone in order to tell you whether it would rain? It is also reasonable to install only the apps from a well-known developer with a good reputation, and only if you really need the app (uninstalling it after you no longer do).