When power meets lack of oversight: bad cop uses data-combing software in sextortion scheme

Indiscriminate data collection and rampant surveillance are bad, but they are the only way to catch the scum of the earth, such as terrorists and sexual predators — that’s what every government tells its people, more or less. We learn to accept this as a compromise and become complacent enough to entrust our data to social media, which in turn can share these data with law enforcement. In any case, as good citizens, we have nothing to worry about, nothing to hide — no skeletons in the closet, no suspicious search history, right?

Cop gone rogue

Unfortunately, history has shown time and again that if the opportunity for mass surveillance and data collection exists, it can be abused in a multitude of ways, and the most innocent can find themselves in the crosshairs. A case that saw a US police officer, armed with a potent data-gathering tool, gaining access to multiple womens’ Snapchat accounts and blackmailing them is another illustration of that.

Former US police detective Andrew Wilson pleaded guilty this summer to one count of conspiracy to cyberstalk women. This week he was sentenced to 30 months in prison and 120 hours of community service for this and another unrelated offense. Now details have emerged about how exactly he committed the crime. Wilson used his law enforcement access to a tool called Accurint to dig up information about the victims. Accurint is a data aggregation platform by LexisNexis that offers detailed profiles on millions of Americans by pulling in data from both public and non-public sources. This information may include names, addresses, emails, phone numbers, employment history, license plates, real property records, criminal records and social media information. LexisNexis’s Social Media Locator tool, available to Accurint users, claims to “scan millions of websites — including hundreds of social networking sites — and the deep Web to uncover information on individuals and any businesses or organizations with which they may be associated.”

According to the FBI, Wilson was involved in hacking of at least 25 Snapchat accounts. For that, he solicited the services of a hacker, who would break into the accounts for him. Since Snapchat has not yet made multi-factor authentication mandatory to use the service, it was probably not too challenging to do.

If a hacked account contained sexually explicit photos, Wilson would then directly contact the victims and ask them to send him more intimate photos unless they wanted their private pics sent to their family, friends, and co-workers. Overall, Wilson stole compromising photos and videos from at least six women, and in some cases, followed through with his threat to publish them online. One victim claimed that her intimate photos were sent to her employer, which almost cost her the job.

Although the way Wilson obtained information about the victims is unusual, the fact that he chose Snapchat is not. There have been numerous reports of attackers succesffully hacking into Snapchat accounts of young women and stealing nude photos that the victims (rather carelessly) stored there.

Photo: Bastian Riccardi/Unsplash

Prosecutors say that Wilson went on a cyberstalking spree in autumn 2020, while police claim he was no longer with the force at that time. In a statement to CNN, the police said that they “immediately disabled” Wilson’s access to Accurint once they found out that he still had it.

Nexis of evil?

Given the scope of information that is available through Accurint, it should not have taken Wilson much time or effort to gain encyclopedic knowledge about his targets. LexisNexis claims to have created 283 million LexID numbers that are tied to individuals. For comparison, as of 2022, the total US population stands at 332 million.

LexisNexis is mostly known for its work with the US government agencies, for which it has received a lot of flak. Namely, the company has been accused of “enabling” unwarranted mass surveillance by the state apparatus. The Intercept revealed last year that the US authorities widely used Accurint to locate migrants subject to deportation. That seemingly ran contrary to LexisNexis’ previous assurances that its cooperation with the ICE (US Immigration and Customs Enforcement) would be strictly limited to targeting people “with serious criminal backgrounds.”

The company has also been embroiled in a lawsuit, with immigration rights activists accusing it of collecting and selling sensetive personal information on millions of people without their consent. The plaintiffs argue that data brokers such as NexisLexis help law enforcement to circumvent judicial oversight and carry on with bulk surveillance. “Using Accurint, law enforcement officers can surveil and track people based on information these officers would not, in many cases, otherwise be able to obtain without a subpoena, court order, or other legal process,” the complaint states.

What’s more, LexisNexis also advertises its software to private entities. A tool called Accurint for Private Investigators promises to provide professionals with “critical information” to “pinpoint criminals or suspects, uncover debt or hidden assets, understand businesses or potential business partners.”

Keeping the guard up

Governments and corporations alike justify mass data collection by saying that it is for the greater good. They argue that it helps them uncover leads, thwart crimes, and punish violators much faster. They also argue that there are checks and balances in place that prevent those with bad intentions from tapping into this giant pool of personal data. However, in reality, not all cogs in that massive surveillance machine will have the public’s best interest at heart. Some of them will be corrupt and willing to abuse their position out of self interest.

And the more power tech giants and government agencies that collect data will amass, the harder it will become to check it. Some can argue that rogue individuals are not representative of the whole system. But one bad apple spoils the whole barrel. Besides, when there’s one, there are many.

Considering the state of things as they are, lulling yourself into a false sense of security is a bad idea. You may not be a digital or a real life outlaw, a billionaire or an A-list celebrity and think that you’re of no interest to the police or hackers. Such an assumption is comforting, but wrong. In reality, everyone is at risk. And the problem is not limited to social media. Big corporations that store massive amounts of client data can leak it as a result of a breach. And it apparently does not take a rocket scientist to cause one, as the story of Lapsus$ group hacking exploits has shown.

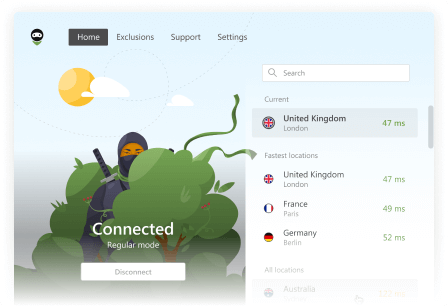

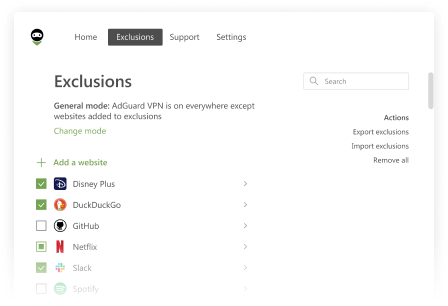

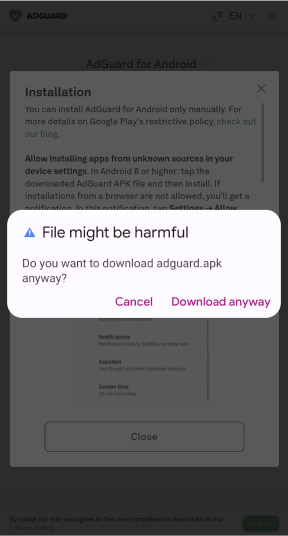

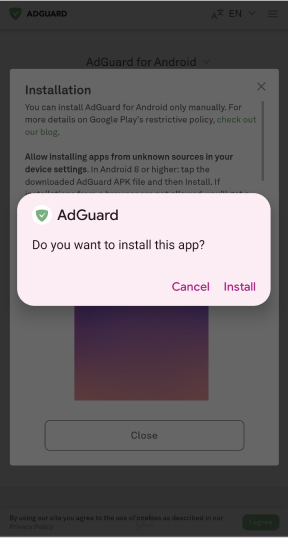

We may blame third parties for mishandling our data, but it’s also our responsibility to keep our data safe. There are a few cardinal rules to follow, such as creating a strong password, enabling multi-factor authentication, and taking advantage of known security tools, including anti-virus software and VPNs. You may also want to install an ad blocker and use DNS filtering software to limit the amount of data collected about you.

However, even if you follow every digital hygiene rule down to a T, learn how to dodge phishing traps etc, there is no guarantee that a person you’re messaging with will be as vigilant as you are and as protective of their own and your data. So, it’s pruddent to make sure your family and friends are also aware of the risks.

Still, perhaps the most important rule is to think twice before sharing something on social media — the internet rarely forgets (and forgives). Someone can dig up your old social media post and try to ruin your career 10 years later, who knows? At least we have seen it happen before. It does not mean you should log off for good, but it’s always better to keep your guard up.