"Sing, Goddess, the wrath": a history of ad blocking, part one

For as long as advertisements have existed, people have been trying to avoid them. No surprise there. An advertisement is an unwelcome communication that distracts attention and intrudes at its own discretion and for its own purpose.

Marketing experts writhed in agony when video cassette recorders first started gaining popularity. "It’s over now," they thought. "TV advertising is dead. People will no longer just switch channels (where they can be caught) or go to the kitchen (where they can still hear the ads). Now they can avoid an ad altogether by just cutting it off!"

Ad fight anatomy

There was no such outcry when banner blockers for web pages first appeared. They became popular gradually, slowly. The first versions of blockers traced images of a certain size in page codes that were typical for popular banner formats.

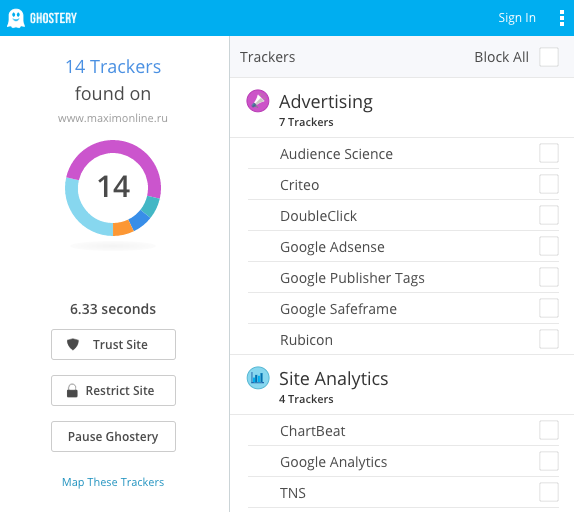

Current ad blocking software employs two main principles: it blocks requests to the source of the ads that are loaded on the page (advertising services and networks, for example, Google AdSense) and hides elements that fit certain criteria from the user’s view. To do this, a program needs a list of rules that describe ad sources and undesirable elements. And this list should constantly be supplemented. Blockers prefer to prevent browsers from requesting ad content, rather than hide it when it has already been installed. This helps save bandwidth and download time.

An apple of discord

A crucial moment in the history of ad blocking occurred in September 2015 when Apple made the new version of its operating system — iOS 9 — available to all its mobile users. This version supported content blocking extensions for Safari. Adblock Plus and other providers of ad blocking extensions for desktop browsers, could now bring their products to the App Store for Safari.

By then, ad blocking had long been available on Android devices. Furthermore, in the third-quarter of 2015, 84,7% of all smartphones sold across the globe worked on this particular OS, and only 13% were powered by iOS. But it was Apple who attracted huge media publicity with this innovation, and media in its turn, stirred up public and professional interest in marketing and advertising circles.

Well, that is Apple’s role in mass culture. This is an iconic company after all, a style seller, a leader of minds and moods. If Apple recognized something, then it really existed. It wasn’t just a marginal half-bootleg version for geeks - on the contrary, if it was something potentially widespread, then it became the standard.

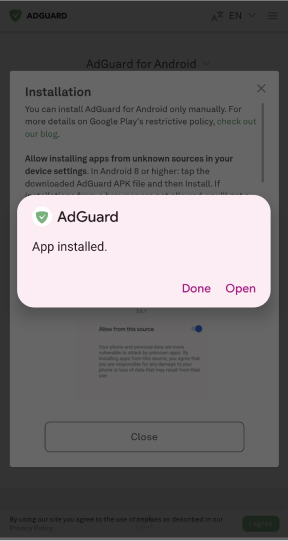

Moreover, Apple users have always been treated as more financially reliable — they tend to have more money, and they spend it more freely than typical Android users. Here’s an example: in 2016 App Store generated higher income for app developers than Google Play, though users downloaded four times more apps from the latter.

If one were to ignore iPhone and iPad owners, then advertisers would stand to lose premium consumers. Nobody would welcome such a loss.

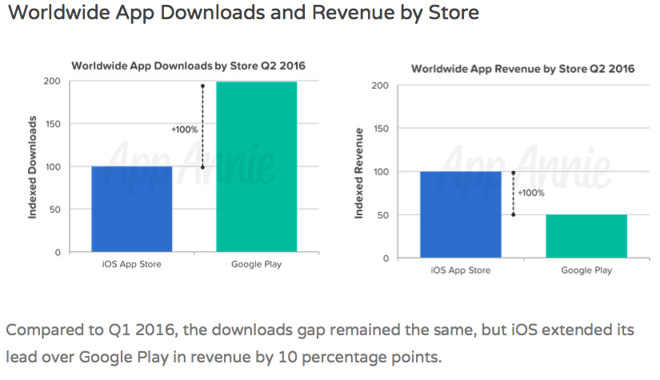

In August 2015, PageFair and Adobe published research which stated that 200 million internet users around the world were already utilizing ad blockers. This number, as well as other statistics provided in their research, have definitely heightened everyone's interest in the topic.

As a result, ad-fighting hype turned into a self-fulfilling prophecy. Media stories regarding the effectiveness of these ad blockers only served to further increase their popularity, and so the word spread as more and more users were made aware of it.

However, we haven’t yet seen any dynamic linear growth in ad fighting. According to Adobe and PageFair, from mid-2014 to mid-2015 blockers were used 41% more often worldwide, while within previous 12 months, such growth showed 70% increase.

It looks like giving blockers access to iOS didn’t "blow up" the consumer market. Nevertheless, it made professionals rethink their own growth and evolution, as well as look at countermeasures that could help platforms to stop losing advertising income, and advertisers from losing sales revenue as a consequence.

Let us review the milestones in the history of services that block ads, as well as user data harvesting activities.

1. The story of products

BLOCKERS

The first web ad blocker originated in the 1980s. It was created especially for a portal named Prodigy, which provided news, weather forecasts, games, expert content, and other services, as well as ad banners.

But the first relatively mass product was Ad Muncher, that became popular in 90's. Light, modest in system requirements, needed no installation, executed in Windows and removing adds in all applications. The only flaw of Ad Muncher — it had to be paid for. It's free now, though.

Ad Muncher logo

AdBlock was created in 2002 as an extension for the Phoenix browser (later renamed Firefox). It didn’t block page requests to ad services, but instead hid already downloaded advertisements from users’ sight - and their mouse devices.

Later, the author of this extension gave up on his project. Then, in 2006, it was taken on by Wladimir Palant who almost completely changed the program code, taught the extension to block requests, and called it Adblock Plus.

Adblock Plus has become the most popular extension for Firefox (19M users) and is also the most popular extension for Chrome (over 50M) and Safari(40M). The latter two are two different products for the two different companies (or at least supposed to be. Adblock was purchased by an unknown buyer some time ago).

Shortly after this deal, Adblock joined the Acceptable Ads initiative. This in itself seems rather controversial, considering the very essence of ad blocking. It implies some standards of ad acceptability. Companies whose ads meet the standards are included in so-called white lists. These ad lists are shown to Adblock and Adblock Plus users, unless they turn this functionality off in their settings.

PROGRAMS THAT OVERRIDE PROTECTION AGAINST BLOCKERS

Apps that oppose platforms' attempts to stop or bypass ad blockers constitute a whole separate niche.

In 2012 the first browser plugin that hides ad blockers from detecting technologies emerged. Later it was complemented by several others.

AD-FREE BROWSERS

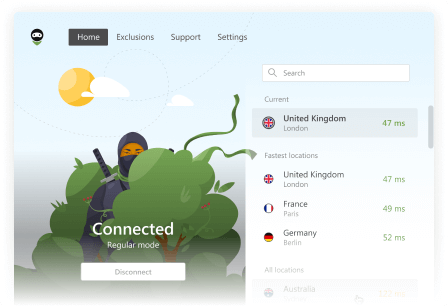

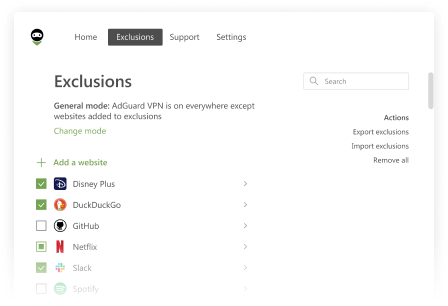

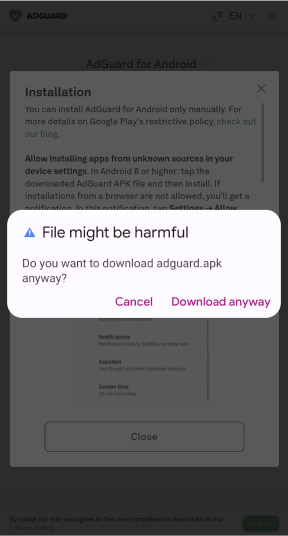

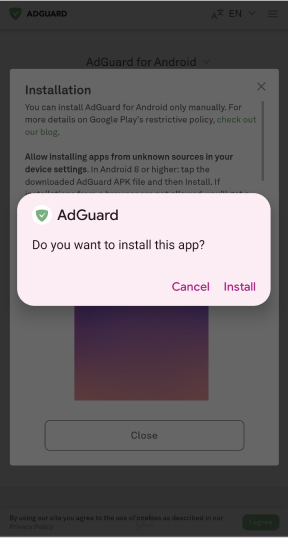

In August 2015, Adblock Plus released an Android mobile browser of its own. It was a step forced by Google Play Store policy and its fight against ad blocking apps. Such apps became outlawed in 2013, when paragraph 4.4 of the Google Play Developer Distribution Agreement prohibited the "development or distribution of Products that interferes with, disrupts, damages, or accesses in an unauthorized manner the devices, servers, networks, or other properties or services of any third party". For some time, Google merely sent letters to ad blocking app developers, warning them about the rule, but in 2016 Google became serious about banning ad blocking apps from their store (for example, AdGuard and AdAway. Adblock Plus had already been removed from the store as early as 2013).

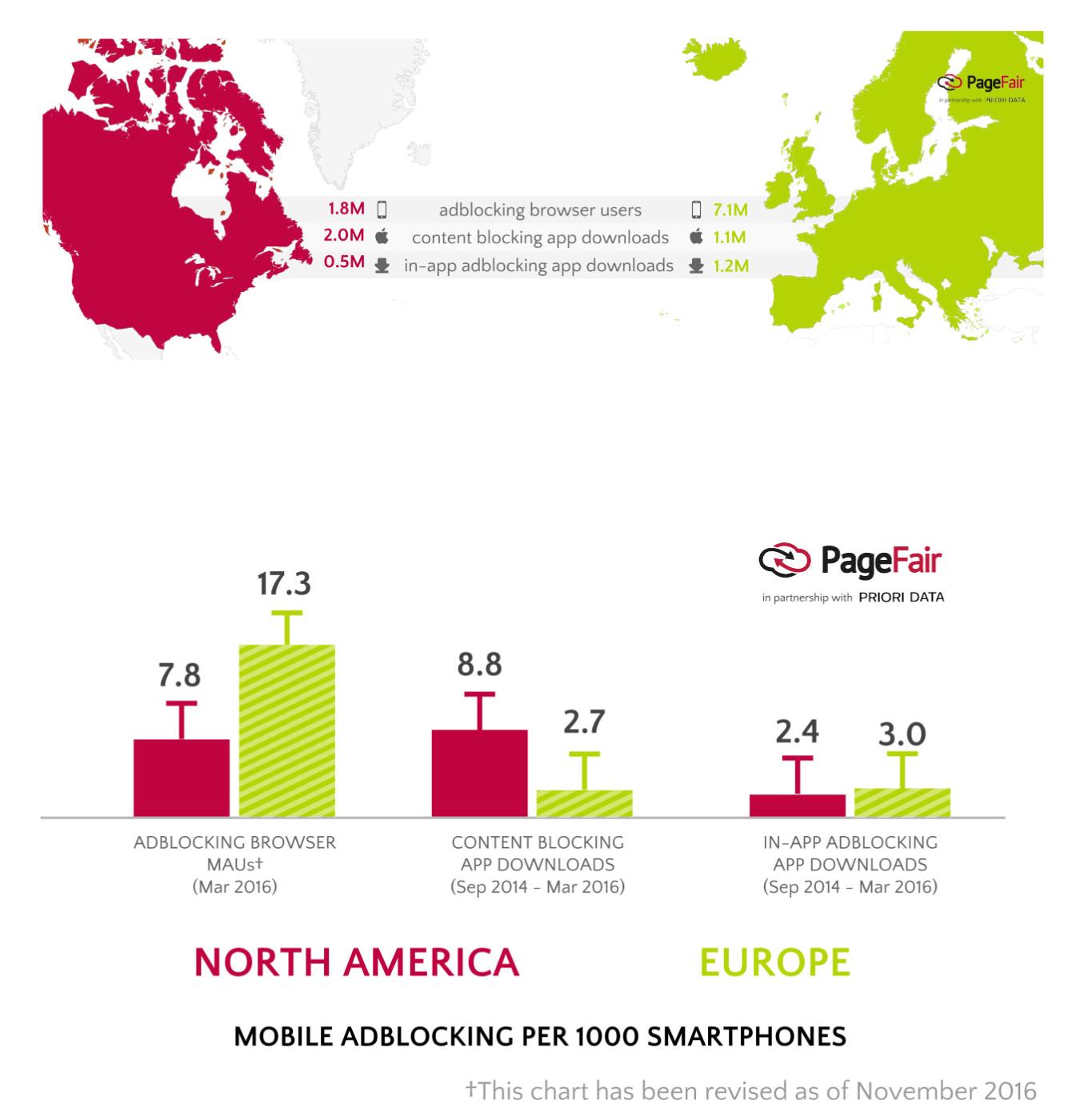

In June 2016 Page Fair analytics came up with information stating that 16% of all smartphones worldwide already had blockers installed. During 2015, people had started to use blockers for mobile devices at an increase of 102%.

However, a huge proportion of these smartphones belonged to users from the Asian Pacific region, and have a pre-installed UC Browser which blocks ads by default. Adding such browsers to the ad blocking apps market is not entirely correct, but rather beneficial for PageFair’s business. The company makes money offering anti-adblocking solutions to businesses, and its target audience must believe that ad blocking is an escalating threat.

In the US, applications that block ad content are more popular than mobile browsers with ad blocking, while it's vice versa in Europe. But numbers show that the amount of both user options is still small.

PROTECTION AGAINST TRACKING AND PERSONAL DATA MINING

Currently, the majority of popular ad blockers are not only capable of blocking advertisements, but also prevent advertising systems from collecting user data. This particular option is also provided by the segment of products that don’t deal with ad blocking. Cross pollination here is significant, but it’s a separate niche and a separate chapter in the internet history.

It would seem that the risks of data collection and the transference of that data between companies are less important to users than comfortable page viewing without annoying advertisements. But gradually, real examples provided by the media are helping people to realize how businesses make money from information about their health issues, habits, family, and financial problems, and how it more often than not isn't in the interests of an internet user.

Data entrusted to one company can show up in the possession of another, and then yet another, being sold, shared, or simply lost. However, the fact that analytical companies guarantee depersonalization and untying of behavioral patterns from personal data doesn’t remedy all possible instances of abuse and manipulation.

Data collected by statistic and analytic systems can be used not only for advertising targeting, but also for credit scoring, insurance cost evaluation, estimation of a certain employee’s qualities while recruiting, as well as criminal and terrorist profiling.

In some cases, mistakes while collecting, interpreting and applying information can cost a person his or her health, career, or even their job. And finally, information collected by business corporations can even fall into the hands of lawbreakers.

In 2015, the largest British online pharmacy sold its customer data — not only the names, ages, addresses, but also medical diagnoses. It turned out that among buyers there were companies accused of unfair advertising and suspicious lotteries, targeting unhealthy elderly people as a potentially easy mark for fraudulent activity. The pharmacy was fined $200,000.

Meanwhile, the popularity of apps and extensions for banning or analyzing advertising tracking slowly grows. One of the most popular products - Ghostery - shows which services are collecting data about the visitor on certain web pages and helps to control it.