Is there a price too high for children's safety? Our comment on Apple's new controversial feature

There is a noisy scandal around privacy and Apple going on recently (yes, again). The world has been divided into alarmists and optimists (most of whom by wild coincidence work at Apple) by a new function called CSAM detection, aimed at preventing child abuse.

We at AdGuard are thinking hard about this novelty: the safety of minors is important, but there is such a great associated privacy abuse potential that some ways to protect from it must emerge. And maybe we can help.

UPD (September 3, 2021):

Apple takes a step back on their CSAM detection initiative. Massive public backlash that took place after the announcement of Apple's controversial child protection program resulted in a statement from the media giant, saying that it's going to:

"...take additional time over the coming months to collect input and make improvements before releasing these critically important child safety features".

No doubt we will hear more about CSAM detection later, but right now it feels good to see public opinion have some real power for once.

A basic overview

And no, before you ask — it wasn't a typo, scam is scam, and CSAM stands for Child Sexual Abuse Material. "We want to protect children from predators who use communication tools to recruit and exploit them", says Apple in a voluminous PDF document (obviously this form of communication was chosen as the most convenient to the reader).

Such a good intention, who can be against protecting little children from a cruel fate? What is the outrage about?

It's about the way they are going to do it. What it looks like: Apple will scan all the photos on your device belonging to the ecosystem (iPhone, iPad, MacBook, and so on) and check them for the signs of child abuse. And then report to the police if any such signs are found.

Well, they will not be viewing your photos like we do, turning paper or scrolling digital pages of a real or a virtual photo album. Here is how they'll do it:

They take a set of images collected and validated to be CSAM by child safety organizations. So it's manual work at this stage.

They turn this bunch of images into hashes. A hash is a string of symbols that describe what is on a picture, and it will stay the same even if the picture gets altered, cropped, resized, and so on.

They upload to your device a collection of hashes for the pictures in the CSAM base. CSAM base is hardcoded in OS image, hence you will always have this base in your device. Although original photos won't store on your device, neverthless, who wanna store base of the CSAM hashes?

They compute hashes for all photos that are to be uploaded to Apple iCloud.

And compare computed hash to the base of CSAM hashes. The comparison happens on the device.

If any matches are found, Apple reviews the account manually. If the reviewer confirms this is actually a photo from the CSAM base, Apple reports the case to NCMEC (National Center for Missing and Exploited Children) backed by the US Congress. It works in collaboration with law enforcement agencies across the United States.

What can possibly go wrong?

Robots can make mistakes

The output of any AI algorithm that involves recognition based on machine learning represents a probabilistic characteristic ("the following action is most likely or likely to occur in the photo"). AI is never 100% sure. There is always a certain share of false-positive results (in our case, there will be situations when a photo is considered to belong to the CSAM collection by mistake).

There might be other flaws in the work of recognition algorithms. For example, neural networks often suffer from overfitting. This happens when they learn — analyze a set of data to understand patterns and correlations and find them later in other data. Overfitting can happen when a training set of data is too small or too refined. And here you are, your AI can't tell a chihuahua from a muffin.

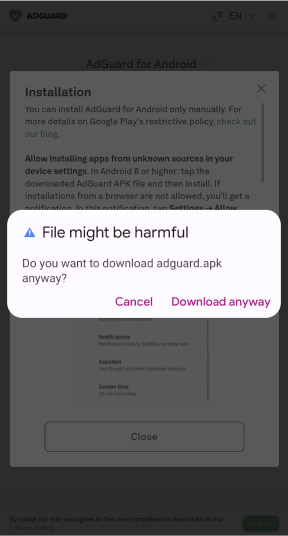

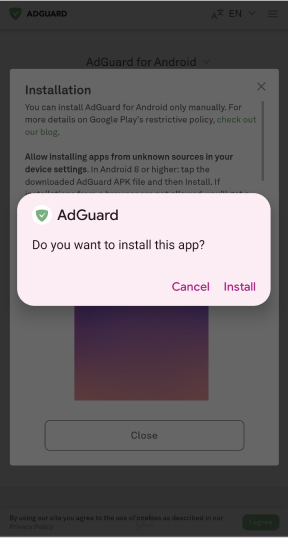

Users have already found pairs of different images with the same hash values. This is called natural occurring NeuralHash collisions. And this is exactly the moment we are worried about.

Image source: Roboflow

Okay, Apple have thought of that and is going to involve people in questionable cases. Who are those people, whom do they report to, what they are responsible for, how pure are their intentions?

People have made mistakes

Just a year ago it has been revealed that Facebook has been paying hundreds of outside contractors to transcribe clips of audio from users of its services. "The work has rattled the contract employees, who are not told where the audio was recorded or how it was obtained — only to transcribe it. They're hearing Facebook users' conversations, sometimes with vulgar content, but do not know why Facebook needs them transcribed", Bloomberg reported.

Actually, it's common practice. Facebook got criticized just for organizing the work so chaotically. In the same August 2019, Google, Amazon, and Apple allowed people to opt-out of human reviews of voice assistants' recordings. Yes, right, random people listen to what other people ask their siris and alexas for and then report it to Apple and Amazon respectively.

It was also found out that voice assistants are more often than you think get mistakenly triggered by more than 1000 words that sound like their names or commands. Among those are "election" for Alexa, for example. Do you want an Amazon contractor listening to what you say about elections thinking no outsiders are near?

Dive deeper: How it works and what are the odds

So when exactly happens the moment when Apple's human moderators start looking at your photos instead of just robots comparing hashes?

Here comes the previously-mentioned probability.

An image's hash is compared to CSAM hashes. The result of this comparison is stored in a so-called safety voucher, a set of data "that encodes the match result along with additional encrypted data about the image", Apple says.

What could this additional data be? Well, just the image itself, as simple and creepy as that. Apple's official documentation on CSAM detection mentions "visual derivative". A picture that shows the picture. A thumbnail. Your photo in somewhat lower quality. This is how it's formulated, nobody knows what exactly it will look like:

This voucher is uploaded to iCloud Photos along with the image.

Using another technology called threshold secret sharing, the system ensures the contents of the safety vouchers cannot be interpreted by Apple unless the iCloud Photos account crosses a threshold of known CSAM content. The threshold is set to provide an extremely high level of accuracy and ensures less than a one in one trillion chance per year of incorrectly flagging a given account.

One-trillion chance to lose looks like a good bet, does it not?

Note that this refers to flagging an account. Flagging comes after a moderator reviews a photo and confirms that it matches one from the base. The possibility of a false-positive hash match signal for one given photo is several orders of magnitude more.

So it's roughly about one in a billion chance that the threshold gets crossed mistakenly. Every chance is one photo. How many photos do people upload to iCloud? We can estimate that. Knowing, for example, that "over 340 million photos are being uploaded on Facebook every day" in 2021, a billion photos will be uploaded in less than a year, and there are more Facebook users than Apple users.

But first, the number of uploaded photos is growing exponentially, and second, if there is a billion-to-one chance of being eaten by a shark, you still don't want to be the "lucky" one. Because it is very serious. You get suspected not of smoking pot in the office restroom, you get suspected of child sexual abuse.

By the way, possessing images from the CSAM base is a crime in the US and several other countries, and Apple would never want to be held responsible for complicity or involvement. So it's a one-way trip: once Apple started looking for them, it will just develop more and more sophisticated ways to do it.

Why should people be worried about CSAM detection?

Let's sum up, the list won't be short.

- Possible mistakes of algorithms with devastating consequences to lives and careers.

- Software bugs. Don’t confuse with point one: it is considered normal for robots to make mistakes at this state of technological advancement. Actually, bugs are normal too, there is no software without them. But the price of a mistake varies. Bugs that lead to personal data leaks are usually among the most "expensive" ones.

- No transparency of the system (Apple is notorious for their reluctancy to disclose how their stuff works). Your only option is to trust that Apple's intentions are good and that they value your privacy high enough to protect it.

- Lack of faith. Why should we trust Apple after all their (and others') privacy flaws and crimes?

- Possible extrapolation of the technology to analyzing and detecting other types of data. Under the umbrella of child protection, a lot of opportunities for companies to dive into your information can be introduced.

- Abuse possibilities. Can an enemy or a hacker inseminate your iPhone with a certain picture that would match a picture from a certain set (so convenient there is a ready-made collection)?

The photo on the right was artificially modified to have the same NeuralHash as the photo on the left. Image source: Roboflow

This explains why we are pondering ways to give users control over the way Apple analyzes their photos. We ran a couple of polls in our social network accounts, the absolute majority of subscribers (about 85%) would like to be able to block CSAM scanning. Hard to believe that all these people plan to abuse children, they just see the risks.

We consider preventing uploading the safety voucher to iCloud and blocking CSAM detection within AdGuard DNS. How can it be done? It depends on the way CSAM detection is implemented, and before we understand it in details, we can promise nothing particular.

Who knows what this base can turn into if Apple starts cooperating with some third parties? The base goes in, the voucher goes out. Each of the processes can be obstructed, but right now we are not ready to claim which solution is better and whether it can be easily incorporated into AdGuard DNS. Research and testing are required.

Otherwise, the only way would be to block iCloud access. It's quite radical to do so for all AdGuard DNS users, but we can make it optional. The question rises, why would you not to just disable iCloud on your device? And you know what, with how things are going, we actually recommend considering this.