Revived anti-ad blocking lawsuit puts users’ rights and the Internet’s future at risk

Almost two years ago, we happily shared news of a major victory in the long-running legal battle between the ad blocker Adblock Plus and the German media giant Axel Springer. Naturally, the court dismissed Springer’s claim that ad blockers violate copyright by modifying a website’s HTML code to remove ads.

Fast forward to 2025 – and the German Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof – BGH) has revived the case. While the headlines focus on publishers and alleged copyright violations, the bigger story is what this means for millions of ordinary users.

A brief history of the Axel Springer vs. Adblock Plus legal battle

Let’s take a look back at the timeline of this 10+ years-long battle and how we ended up where we are today.

The beginning (2015): Axel Springer, one of Germany’s largest publishers, began a legal campaign to ban Adblock Plus, arguing that it harmed their business model and violated competition law.

2018 outcome: In April 2018, Germany’s Federal Court of Justice rejected Springer’s claims, ruling that ad blocking is legal.

Shift in strategy: Springer then pivoted to copyright law, claiming that modifying the DOM/CSSOM (the structures created by a browser to render a webpage) amounts to altering a computer program — and therefore infringes copyright.

2022 ruling: The Hamburg Regional Court dismissed this claim.

2023 ruling: The Hamburg Higher Regional Court also rejected it, holding that ad blocking does not interfere with program code.

July 31, 2025: Germany’s Federal Court of Justice revived Axel Springer’s lawsuit against Adblock Plus and sent the case back to the lower court. The judges argued that earlier courts did not sufficiently analyze the technical aspects of how browsers and extensions work. The lower court must now re-examine whether ad blocking constitutes a copyright violation.

Meanwhile, eyeo (the company behind Adblock Plus) continues its fight – not only to defend its product, but also to uphold users’ rights to privacy, security, and control over their online experience.

"This case is about so much more than ad blocking: it puts the privacy and security of millions of users at risk. From a legal perspective, it was sent back to the lower court to clarify technicalities. And while we’re confident in the case’s ultimate outcome, if the claims made by Axel Springer were upheld, blocking invasive trackers, changing font sizes for readability or even zooming in on a webpage, might be construed as copyright violations. It would all be in the hands of the website owners if this or that user preference on their page’s rendering would be a violation, or not, and we are convinced that no single company should have such powers and prohibit users from making their own choices.

This current case marks the sixteenth time that we are fighting for user rights in court. Our commitment to user freedom and digital self-determination remains the same and we will continue to champion these values."

– Cornelius Witt, Director of Global Public Affairs, eyeo

Possible consequences

This ruling could have wide-ranging and unexpected consequences, reaching far beyond ad blockers themselves. We’ll try to cover some of them that may not be obvious at the first glance.

All browser extensions, not just ad blockers

This legal battle isn’t just about ads. Ad blockers modify the DOM (Document Object Model) so that the user’s browser displays pages differently – hiding or removing certain elements. Now, Axel Springer claims that this interpretation of 'bytecode' by browser engines, could be protected under copyright law.

When you open a website, the server sends its code (HTML, CSS, JavaScript) to your browser. Your browser builds a DOM – a local "blueprint" of the page – to render it on your screen. Extensions interact with this DOM, modifying how the page looks and works for you, but the original code from the server remains untouched, only the local copy is changed, to suit your preferences.

And this isn’t unique to ad blockers – this mechanism is used by countless other extensions:

- Accessibility tools that change fonts for dyslexic readers.

- Dark mode extensions that invert colors.

- Translation tools that replace original text with another language.

- Password managers that inject login fields.

etc.

If courts rule out that modifying the DOM equals "copyright infringement," it would threaten the very foundation of the browser extension ecosystem. In other words: any tool that enhances the user experience could suddenly become illegal.

User freedom and digital rights

When you make a paper plane out of an ad flyer or doodle on it, no one calls that "copyright infringement". But if you use a digital tool to do the same thing, suddenly it might be treated as illegal.

That poses a much broader question – do users have the right to control what they see on their own devices? Or must they consume content exactly as publishers dictate, even if it undermines privacy, accessibility, or security?

If everyday tools — those countless extensions used by millions of users — are restricted or banned, then it’s not just about loss of control, it’s about privacy and even security risks as well. Users might be forced to accept invasive ads and tracking, and even malicious ads (malvertising) could become more widespread.

Users around the world

It would be short-sighted to think that this case is local for Germany and therefore unimportant in the grand scheme of things. Germany often sets the tone for digital policy debates in Europe as it did with the GDPR privacy law. If German courts decide that DOM modifications are a copyright violation, it won’t just affect German users, other EU countries are likely to follow. And then nothing stands in the way of this precedent spreading worldwide.

AdGuard's CTO commentary

Our CTO and Co-Founder, Andrey Meshkov, has looked into the technical side of the allegations, and we share his commentary below:

I’d like to examine Axel Springer’s arguments from a technical perspective, starting right from the very beginning — from the origins of the Internet and what it was meant to be.

Axel Springer alleges that browser-based ad filtering constitutes a copyright infringement, arguing that the HTML source code of a webpage dictates the browser how to render a website and all subsequent actions and data that are created or downloaded by the browser during that process are part of a big "website program:. As a result, websites would basically be cloud-based applications that should have copyright protection as computer programs and changing how websites are rendered would be a copyright violation.

The World Wide Web was originally conceived as a network for sharing documents. In other words, Bob could publish a document on his “site,” and Ben could download it and read it.

The W3 world view is of documents referring to each other by links.

—World-Wide Web, 1992, Tim Berners-Lee, Robert Cailliau

Now let’s take one step further: how exactly would Ben read that document? The simplest way was to open it in a program like Notepad, or in any of hundreds of other text editors. And of course, the way the document looked — font size, color, typeface, and so on — was fully controlled by the editor. The document was being opened on the user’s computer.

One of the truly groundbreaking ideas of the WWW was hyperlinks, and to make navigation easier, the first web browsers were created. But just like with Notepad, the browser itself controlled how the document was displayed.

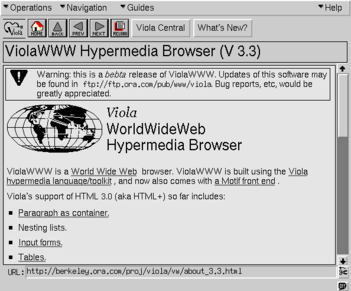

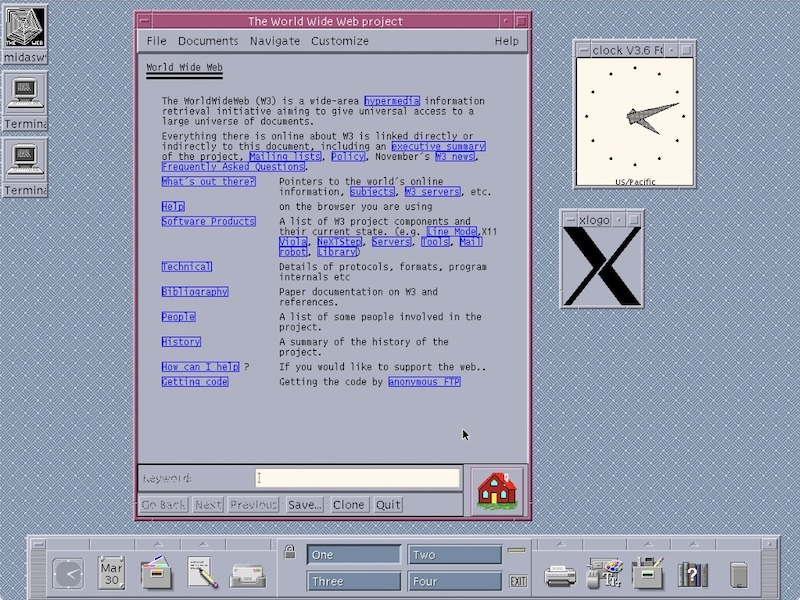

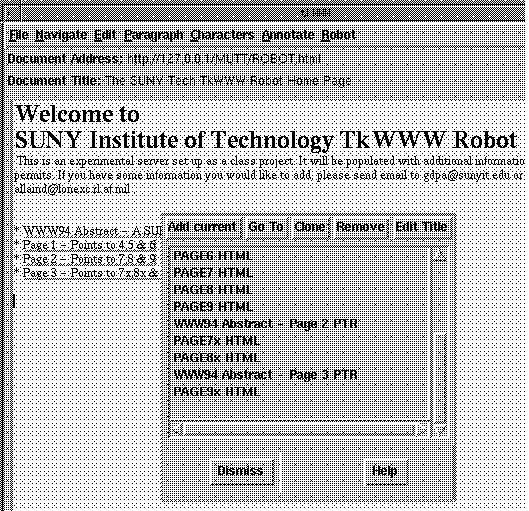

Here are a few examples of the earliest browsers:

Incidentally, all of these browsers would be illegal if Axel Springer won this case — since none of them could display Axel’s beloved ads.

As the web evolved, new concepts emerged — CSS, JavaScript, more dynamic documents — but the essence remained the same: they were still documents. The browser downloads them to the user’s machine and displays them for reading. That’s important: by the time you view it, the document is already on your computer, and the browser is simply presenting it to you.

Over time, browsers began following common HTML/CSS standards (with varying degrees of success). Interestingly, the specifications themselves explicitly allow users and browsers to apply their own styles. For example, see 3.1.5 Default style sheet and 6.4.2 !important rules:

Both author and user style sheets may contain ‘!important’ declarations, and user ‘!important’ rules override author ‘!important’ rules.

The specification even explains why:

This CSS feature improves accessibility of documents by giving users with special requirements (large fonts, color combinations, etc.) control over presentation.

Skipping or disabling certain content has also long been part of browser functionality. Here are some of the most commonly seen examples:

- Virtually all browsers let users to disable JavaScript completely (for security or performance reasons).

- The majority of browsers allow disabling image loading (historically to save bandwidth and speed things up).

- There are many text-only browsers (like Lynx) or speech browsers, which ignore CSS and complex layouts and display content in simplified form.

From a standards perspective, HTML/CSS code is not a single, fixed-output “program.” It’s content that can be rendered in different ways depending on the context. In fact, HTML was designed with graceful degradation in mind: content should remain usable even if certain features (images, styles, scripts) aren’t available. That directly undermines the idea that there’s only one “required” way for a site to appear.

Frankly, I’d even dispute the use of the word program when talking about web pages. A website’s pages are no more “programs” than Microsoft Word documents are. The only real program in this picture is the server, which prepares documents for the user to download.

This case is nothing less than a threat to the very Internet as we know it. I could list countless examples of what would suddenly become illegal, but let’s start with the most basic: even choosing a browser could become a problem. If you follow the letter of this lawsuit, there would only be one “correct” way to display a publisher’s content. Any deviation from that, and the browser would be in violation. That would outlaw most browser extensions, nearly all modern browsers, and — ironically — the web standards themselves.

To me, that’s putting the cart before the horse. And as an engineer, I’ll stress something else: what they’re asking for is technically impossible. Even if publishers turned every page into static images, those images would still render slightly differently from one browser to another. The only foolproof way to achieve what they demand would be to go back to print. But even then, I suspect they might try to forbid us from folding the newspaper or flipping through the pages — and demand that we report back after reading each article.

— Andrey Meshkov, AdGuard's co-founder & CTO

Summing up

We at AdGuard believe the key issue here isn’t about ads, it’s about whether people are allowed to control their own experience — the content they see and the software they use. If blocking unwanted tracking, pop-ups, or autoplay videos can suddenly be treated as a copyright violation, it puts privacy, accessibility, and even cybersecurity at risk. Undeniably, this decision by BGH is a setback, but we remain cautiously optimistic and hope for a fair and reasonable court decision. In the meantime, we'll continue providing our users with the right to control the web the way they want to, fully within the law.