Cloudflare says Encrypted Client Hello might ‘solve privacy for good’. The reality is not that simple

A cutting-edge technology that is “filling the privacy gap in our existing online security infrastructure” and that, if widely adopted, “might even solve privacy for good.” Sounds promising, right? That’s how Mozilla and Cloudflare describe Encrypted Client Hello (ECH), a protocol that encrypts the entire “hello” message or the first communication between your browser and a website’s server.

We believe ECH is indeed a major element of Internet privacy, and the importance of its support by such major players as Mozilla, Chrome, and Cloudflare cannot be understated. At AdGuard, we have added ECH support in our Windows, Mac, and Android apps, because we believe in the technology’s potential to make browsing more private. AdGuard’s ECH support works across all apps and browsers that AdGuard filters. But is ECH the missing piece of the puzzle that will solve privacy and defeat censorship once and for all? As much as we would like it to, it is unlikely.

And before we pour some cold water on the excitement over ECH and its supposed invincibility to censors, copyright authorities, peeping toms, and other prying eyes, we need to take a step back and cover some basics.

What is ECH and why do we need it?

Imagine you are sending a letter to your friend. You seal the envelope and write their name and address on it. No one can open the envelope and read your letter without breaking the seal. But anyone can see who you are sending the letter to by looking at the address.

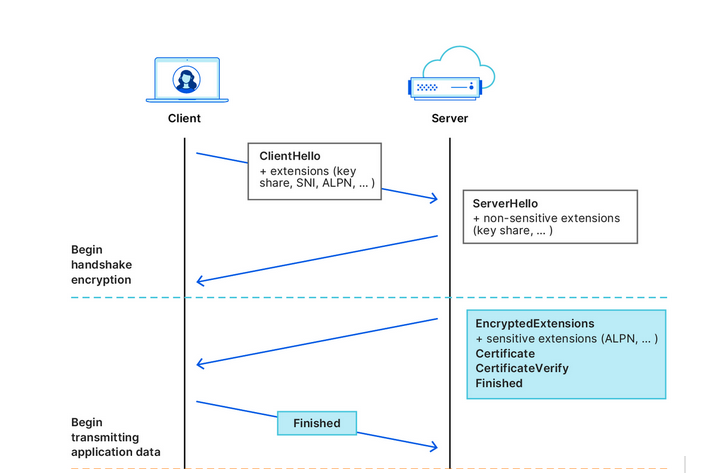

That’s kind of how HTTPS, a default protocol that is used by over 84% of websites, works. The first piece of information your browser communicates when establishing an encrypted connection to the website is known as “Client Hello.” Some information in Client Hello, such as SNI (Server Name Indication, which is a way for your browser to tell the server which website it wants to connect to), is not encrypted. This, in turn, means that network operators, including your ISP, can see it. Having received the Client Hello message, the server replies with some information known as “Server Hello” to complete the ‘handshake’ with the device.

Source: Cloudflare

After that first greeting, the data your browser exchanges with the server is encrypted, so that only you and the website can see what’s inside it. But by that point, your internet provider already knows the name of the website you are visiting. For example, if you went to www.google.com, your internet provider couldn’t see what you were searching for, but they could see that you were using Google.

What we’ve described above is how a TLS handshake works. TLS stands for Transport Layer Security, which is a cryptographic protocol that provides end-to-end security for data sent over the Internet. To be more technical, the first “Client Hello” message that your browser sends in clear text to the website’s servers contains not only the SNI, but also the TLS version and an encryption algorithm. But the main point is it’s not encrypted, so anyone who can see the network traffic can also see the website name your browser is requesting.

The question is, how can we shield that first piece of data that is not encrypted and that exposes our browsing habits?

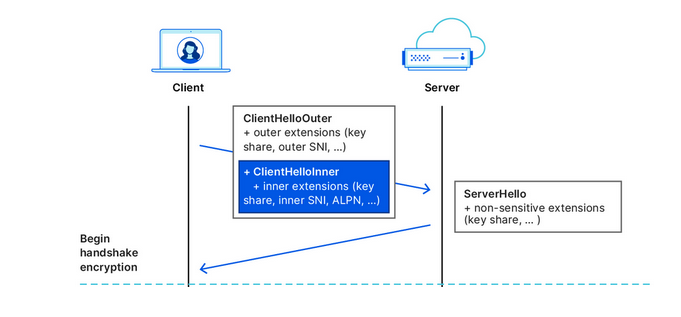

This is where the Encrypted Client Hello protocol comes in. In simple terms, ECH encrypts the Client Hello message containing SNI, which, as we’ve already mentioned, indicates the name of the website you are visiting. Instead of showing the website’s real domain name, like www.google.com, to any external observers, your browser only shows the name of a so-called client-facing server, behind which multiple backend servers with their own domain names are hidden. The client-facing server has a general domain name: for example, Cloudflare uses cloudflare-ech.com as its client-facing server name. But how does your browser know which information to send to it to connect to a specific website?

The client-facing server acts as a middleman that has a special decryption key with which it opens your inner letter and sees your website name. Then it forwards the request to the real domain and sends back the response. This is possible because ECH splits Client Hello into two parts: the outer part contains non-sensitive information like the name of the client-facing server, and the inner part contains the inner SNI indicating the domain name of the backend server, which is the website you want to visit. To continue with our letter analogy: it’s like having the same address written on letters to different recipients, and having to use a magic wand to break the seal to see the inner letter with an actual address.

Source: Cloudflare

What is the situation like with ECH adoption?

In recent months, more and more industry players have begun to warm up to ECH. Google started shipping the feature in Chrome 117, while Chrome 118 became the first stable release of Google’s browser with ECH support. In Firefox, ECH is on by default as of Firefox 118, but only works if you have DNS-over-HTTPS enabled. Edge is also testing ECH, but has yet to roll it out in a stable version.

However, support for ECH from the browser side means little without being reciprocated from the server side. It only means that a browser can send encrypted ECH messages to the servers that support this protocol. So, the move by Cloudflare, the most popular CDN provider on the market, to also support the protocol has made a big difference in the ECH adoption. Cloudflare, which handles around 20% of all the traffic on the Internet, announced that it began supporting ECH for all customers on free plans at the end of September, and encouraged paid customers to apply for the feature.

The protocol, however, still has a long way to go before it is widely accepted. As of right now, many of Cloudflare’s free domains are missing information about ECH in their DNS records, so Chrome can’t use ECH for those websites. But, since the ECH rollout is still in its early stages, this issue will likely be resolved over time.

So, is privacy solved?

As much as we would like to see it happen, declaring privacy solved is wishful thinking.

On the one hand, the universal adoption of the ECH, if it happens, will render useless some of the tried-and-tested blocking techniques employed by Internet authorities around the world to tackle online piracy, incur geo-fencing, and impose censorship. For one, law enforcement authorities will find it more difficult to target specific websites based on their names, because they will be hidden by the ECH.

However, this does not mean that censors won’t be able to clear this hurdle. It may require some adjustments on their part, but blocking will still be possible.

ECH’s weak spots or potential blocking methods

Now, we’re going to play devil’s advocate and give you some concrete ways that censors can try to block websites despite the implementation of the ECH.

One way is to “cut” the ECH from DNS records. To establish an ECH connection with a server, your browser needs a special DNS record from that server. This record tells your browser which domain name and decryption key to use in the outer and inner part of the ECH. However, if your DNS traffic is not encrypted, which is the case for most users, then anyone who can see your DNS queries, such as your ISP or a censor, can also see the ECH record. They can use this record to identify and block your ECH connection. Of course, if users have encrypted their DNS traffic, then this method won’t work.

A cruder, but a fairly effective way is to block all known client-facing servers, such as clouflare-ech.com. Realistically, there shouldn’t be many of these servers, so it should not be hard for censors to identify and block them all. But this method is very risky because it could break the Internet for many users. If the censors block all the servers that support ECH, then the browsers will not be able to establish a connection with the websites that have ECH enabled. This may, in turn, prompt Cloudflare to disable ECH for countries with strict internet censorship. It remains to be seen how Cloudflare will react if their client-facing server gets blocked by censors in countries like China or Russia. They will face a difficult choice, for sure. Another pitfall that awaits those banking on ECH as the ultimate solution to all privacy-related problems is a risk that website owners will simply refuse to adopt it or will opt out of the protocol because of the very same reason. If censors target ECH and make websites that enable it unaccessible, then website owners might want to disable the ECH support rather than lose their visitors.

There’s no denying that ECH is an exciting and a very promising technology that aims to make the Internet more private. However, it is not foolproof, and should not be regarded as a panacea against surveillance. Moreover, its widespread adoption favors the use of certain CDN services, such as the one offered by Cloudflare. While these services may not be problematic in and of themselves, their promotion as a side-effect of the ECH adoption risks making the Internet even more centralized than before. Only time will tell if this is for better or worse.