Facebook, DuckDuckGo, WhatsApp’s new privacy tools, Signal’s misfortune and more. AdGuard’s digest

In this edition of AdGuard's digest: DuckDuckGo rights the wrong, laptops spy on children, health apps — on women, WhatsApp unveils new privacy features, Messenger expands end-to-end encryption, as Signal suffers in an attack.

DuckDuckGo will block Microsoft trackers, but not everywhere

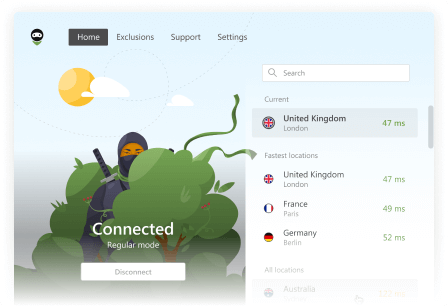

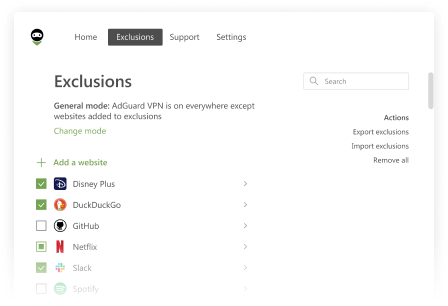

DuckDuckGo, which came under fire earlier this year for allowing Microsoft trackers to run in its browser, is trying to regain the trust of the privacy-minded crowd. The company has announced that it wouldn't cut Microsoft trackers any slack any longer, and would start blocking tracking scripts from Bing and LinkedIn domains from loading in DuckDuckGo's mobile browser and extensions.

While DDG says that it has been working "on an architecture for private ad conversions", for the time being it still needs the Microsoft's helping hand delivering ads in its privacy-focused search engine. Thus, following a click on a Microsoft-provided ad in the search, DuckDuckGo will allow a tracking script to load on the advertiser's website. However, the user can disable ads in the search settings.

DuckDuckGo came clean about its tracking deal with Microsoft only after it was uncovered by a security researcher. Thus, it may have no other choice but to expand its third-party tracker protection to Microsoft to save face (what has remained of it). However, it's a welcome step: less tracking is still less tracking.

School-issued laptops spy on students after class

Laptops issued to students during the pandemic have been keeping tabs on them in and after class, and will continue doing so come the next school year. According to a new survey, 89 percent of teachers in the US say that their schools monitor students online, and that 80 percent of this monitoring "occurs on school-issued devices".

In most cases the monitoring is used to flag students for disciplinary violations and not self-harm or threats of violence. Students cannot quite wind down at home as well — about half of students and teachers report that activity monitoring continues outside school hours. Moreover, during that time, alerts from school-issued laptops can be forwarded directly to "a third-party focused on public safety" such as police. 44 percent of teachers say such round-the-clock surveillance indeed resulted in students being contacted by some type of law enforcement.

And while students, at least, may suspect that everything they search for on their free, school-issued Chromebooks is hardly a secret, it turns out that the spying software can also pull in the data from their private phones. When the student plugs in their phone into the laptop, the monitoring software can slurp up photos from the phone and scan them, The Wired reports.

Sadly, the pandemic has normalized intrusive surveillance, and, as it happens so often nowadays, the noble goal of protecting children is used to justify blanket spying. While the spying tools' contribution to the students' safety is up for debate, they trample on children's privacy, instill fear into them and invite excessive policing.

Popular period and pregnancy apps leak data

A new Mozilla research has found that the vast majority of popular reproductive health apps fall short of protecting users' privacy. The researchers have studied 10 period tracking apps, 10 pregnancy tracking apps and 5 wearable devices. 18 apps failed to clear Mozilla's threshold to be considered safe enough to be used, while smart devices (Garmin, Apple Watch, Fitbit, Oura Ring, Whoop Strap 4) received the greenlight.

Massively popular Flo period tracker was chastised for having a "spotty" track record and potentially buying data from third-party sources. Germany-based Clue period tracker was faulted for sharing personal data with advertisers by default, using date of birth as an ad identifier and not requiring a strong password. Some apps were flagged for misleading or vague privacy policies, others for collecting huge amounts of data and sharing it with third parties, including law enforcementand Facebook.

The findings are a stark reminder that most apps that handle sensitive health data are neither private nor secure. We urge users to give their apps only the most necessary permissions, as well as study their privacy policies.

WhatsApp's new privacy feature to allow users put on invisibility cloak

As part of its latest privacy-focused update, WhatsApp is giving users the ability to leave a group without a bang. From now on, only group admins will be notified if you decide to take a French leave. Users will also be able to choose who can see that they're online: no more fielding questions from pesky conctacts who saw you being online and not responding to their messages.

In another update aimed at boosting privacy, WhatsApp said it would be blocking screenshot-taking for 'View Once' messages. It was previously possible to take a screenshot of a message shared through the privacy-oriented feature, but now this loophole would be closed. Indeed, what is the point of 'View Once' messages if they can be viewed multiple times?

The host of new features promise to make the WhatsApp experience a bit more private for users. However, it might not be enough to redeem it in the eyes of those who remember its more questionable practices, such as employing an army of content moderators to act on user reports. After all, WhatsApp still shares data with Meta, which is notorious for its lackluster privacy protections.

Speaking of the devil…

Meta tests default end-to-end encryption in Facebook Messenger

Meta might be dragging its feet on the promise to introduce end-to-end encryption across all its chat apps, but it is not abandoning the idea. The company has announced that it would be turning on end-to-end encryption for some individual chats on Messenger by default as part of a new test. The most frequent chats of those in the test group would be automatically encrypted.

Unlike WhatsApp, which has default end-to-end encryption, Messenger still lacks that additional layer of security. Thus, the burden falls on users to enable end-to-end encryption by entering into a 'secret conversation' mode for each individual chat. Earlier this year, Messenger also rolled out an op-in end-to-end encryption feature for group chats and calls.

Additionally, Meta said that it would allow users to store their end-to-end encrypted conversations not on the device, but in the "secure storage" on Meta servers. Meta said that it won't have access to the messages, unless the message is reported by the user. In order to restore the chat history on a new device, users will need to either set a PIN or generate a code. They also might use a third-party cloud service, such as iCloud, to store a secret acceess key to the backup.

An unencrypted messenger sounds like an anachronism in 2022, so we can only hope that Facebook makes good on its earlier pledge to encrypt private messages in Messenger and Instagram 'sometime in 2023'.

Police uses Facebook messages as evidence in abortion case

The timing of the abovementioned Messenger update is curious, as it comes right on the heels of Facebook's admission that it had turned over a teen and her mother's DMs to police. That resulted into both women being hit with abortion-related charges.

According to the court documents obtained by the Motherboard, Facebook turned over the chats in response to a search warrant from Nebraska police. The messages showed the teen and her mom allegedly discussing how to take an abortion-inducing drug and dispose of the fetus.

The alleged abortion was performed later in the pregnancy than allowed by the state law. Meta confirmed that it handed over the sensitive data to police, but claimed that "nothing" in the warrant mentioned abortion. The case unfolded in early June before the US Supreme Court ended federal abortion protections. The latter ruling renewed concerns about how apps and social media handle sensitive medical data.

Meta denied that its encryption update has anything to do with the abortion controversy. Moreover, end-to-end encryption by itself does not offer bulletproof protection in cases like this. If a secret encryption key is stored on the company's servers, the data can still be easily unscrambled by anyone who has it. Messenger's new 'secure storage' feature is apparently aimed at preventing this from happening.

Nobody's perfect: Signal users' phone numbers exposed in third-party breach

Your app may be as secure and private as it gets, but as long as it relies on third parties to operate, it can never be immune from breaches like the one that hit Signal, a king among the most secure messaging apps.

End-to-end encrypted messenger Signal has become collateral damage in an attack on telecommunication giant Twilio, which was breached in early August. The data of 125 Twilio's customers (Signal among them) was compromised as a result of the attack. Twilio does phone number verification for Signal.

Signal said that attackers might have obtained access to phone numbers or SMS verification codes of 1,900 users. The attackers looked for three numbers specifically, and one user reported that someone had re-registered their account. Signal is responding to the breach by notifying and unregistering all affected users on all devices so that they can sign up again. Users are also advised to turn on the feature that requires them to enter a security PIN before an account can be activated.

While the breach is not a good look for Signal, it also underscores the importance of end-to-end encryption and other security measures taken by the platform. Owing to them, bad actors won't not be able to access message history, profile information or contact lists of those affected. It must be noted that end-to-end encryption is not a panacea, and will only serve its purpose if implemented properly, so that the data is not compromised due to weak algorithms or a leak of encryption keys.