Dazed, tracked & confused: How unaware and helpless is public about data privacy?

As we spend an increasing chunk of our lives online — more than 6 hours a day on average — we face a growing challenge: how to protect ourselves and, specifically, our personal data in the digital world. Many private firms, such as social media giants, advertisers and data brokers, are hungry for this data. They harvest it and milk it for profit, sometimes without our knowledge or expressed consent. The government also taps into the online data pot, often through intermediaries to bypass legal safeguards.

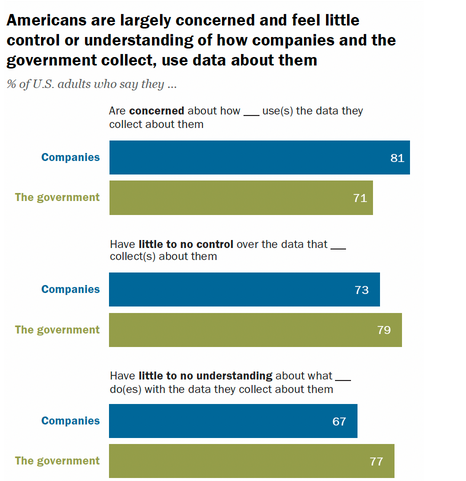

For the longest time, this covert and shady operation has taken place out of the public eye. But now, more and more people smell something fishy. A recent Pew online privacy survey found that 8 in 10 Americans are concerned about how companies use the data they collect about them, and 7 in 10 harbor the same apprehensions about the government. But while these numbers clearly show that Americans care about privacy, the most interesting finding is that the lion’s share have no idea what is really going on behind the scenes and how they can regain long-lost control of their data.

Americans concerned but in the dark about how their data is used

According to the survey, 73% of Americans believe that they have “little to no control” over the data that the companies collect about them, while 79% believe the same about the government. Even more worrying, 2 out of 3 have “little to no understanding” what it is exactly that companies do with their data, and even more are in the dark about what happens with their data once it falls into the government’s hands.

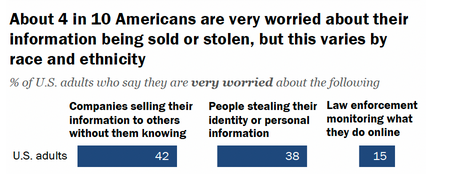

It can be indeed challenging to understand what companies do with the information they collect from you, as they apply it for various purposes depending on their goals. Some companies (many, in fact) utilize this data for advertising — they learn about your preferences and online behavior to target you with highly specific ads. This is done by almost every manufacturer, from a smart TV maker to a car company. Companies may also employ the collected data to personalize products, measure the effectiveness of their marketing campaigns, and conduct research. Most consumers probably don’t mind these applications, except for advertising. However, there are also other uses of the data that are more concerning, such as government surveillance or selling it to third parties who can exploit it for any purpose they want. As for Americans, they seem to be more worried about their data being sold without their consent than about the government keeping tabs on their online activity.

About 4 in 10 (42%) say that they are “very worried” about companies selling their information to others without them knowing, while every 7th American (15%) say they are “very worried” about law enforcement monitoring what they do online. 15% may not sound like a lot, but we mustn’t forget that companies are not only selling the data, such as location, to other companies, but also to the government.

Among the companies up to their necks in the business of selling, or as they like to call it, sharing data, the social media giants are at the forefront. They have millions of users and make billions of dollars by selling their data to advertisers. For example, last year, Meta made a whopping $112 billion from this trade, while TikTok's parent company, ByteDance, reported $29 billion in ad revenue. While about 82% Americans now use social media, and juggle an average of 7 accounts, the vast majority of them (76%) say they have “very little or no trust” that social media executives will not sell their personal data without their consent.

And they are right to be distrustful, because this has already happened, and more than once. For instance, in 2022 Twitter (before it became “formerly Twitter”) was fined for selling users’ data for targeted ads illegally, while claiming that it would be used only for security purposes. In 2018, it was exposed that Facebook gave its partners, including Amazon and Microsoft, almost unlimited access to its users’ data, without asking users’ permission first.

Learned hopelessness: concern does not necesarily mean action

One would think that increasing concerns about online privacy would translate into concrete steps to remedy the situation. And to some extent, it’s true. Most Americans believe they are doing everything in their power to safeguard their privacy online — 78% say they trust themselves to make the right decisions about their personal information.

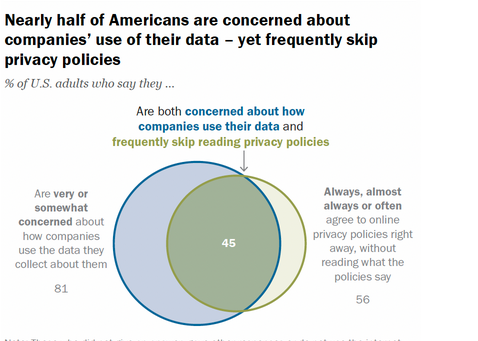

But does that mean they are confident that their privacy is actually protected? Hell, no. About 3 in 5 Americans say they are “skeptical that anything they do will make much difference.” In short, many people feel like they have to take it or leave it, and that the options presented to them are just for show. One of the things that most Americans apparently believe is futile is reading privacy policies. More than half say they “always, almost always or often” skip them. The most glaring example of “not walking the talk” is the 45% of US adults, who say they are “very or somewhat concerned” about how companies handle their data and at the same time admit to not reading privacy policies.

While reading privacy policies is a basic rule of digital hygiene that we urge you to follow, we would be the last to throw a stone at those who avoid lengthy and confusing texts that companies often use as their privacy policies. Sometimes a privacy policy is not even at one place, and you have to read addenda and other supplements to get a full understanding about what the company will do with your data.

With so many privacy choices to make every day, most of which are meaningless, it’s easy to get discouraged. And when people see how big and hopeless the challenge is, many quit — 37% of Americans say that they are “overwhelmed” by figuring out what they need to do.

Awareness: the key to privacy protection

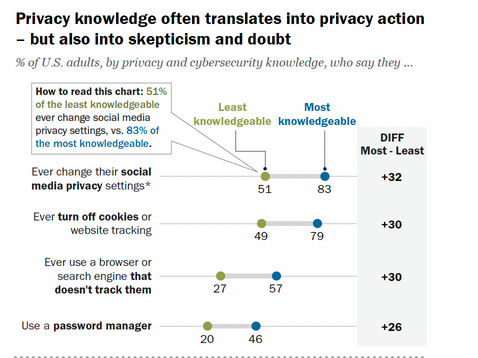

It's easy to get lost in the sea of privacy choices, and even harder to tell which are real and which seem designed to confuse you (like the infamous “incognito mode”). The key to navigating these stormy waters is to learn more about privacy and cybersecurity — and perhaps you don't need a Pew Research survey to tell you that. According to the survey, those who are the most knowledgeable about privacy and cybersecurity are more likely to be taking more concrete steps to protect their personal information. These include adjusting social media settings, turning off cookies or website tracking, using a privacy-focused browser and search engine, and delegating the task of remembering all your passwords to a password manager.

While only 68% of Americans say that they have changed their social media privacy settings to manage their online privacy, 83% of the most privacy-savvy Americans have done it.

To see that people are taking their privacy in their own hands is encouraging, but the privacy protection methods singled out in the survey are far from being enough. For one thing, changing your social media privacy settings may not do much.

As for the other privacy protection methods listed by Pew, they are all valid, but there are many other ways to boost your privacy even further. You can use a VPN, which will encrypt your data and route it through a server, so that your ISPs or public Wi-Fi provider could not see what you’re doing online. You can also use an ad blocker: it will block tracking requests, and make it more difficult for third parties to track you around the Web. Changing your default DNS resolver, the one provided by your ISP, to the one that blocks ads and trackers, may be another step. For more advanced users, a private DNS may come in handy. A private DNS is a DNS server that, in addition to the benefits of a public DNS server (such as traffic encryption and ad blocking), provides features such as flexible customization, DNS statistics, and parental control.

However, knowing which tools may help you to improve your privacy is not enough either. You should also research services you’re about to use, and make sure they are not wolves in sheep’s clothing, or, in other words, imposters, who pretend to protect your privacy but actually compromise it — just like this free VPN service, which claimed to keep no logs, but exposed over 360 million user records in a breach.

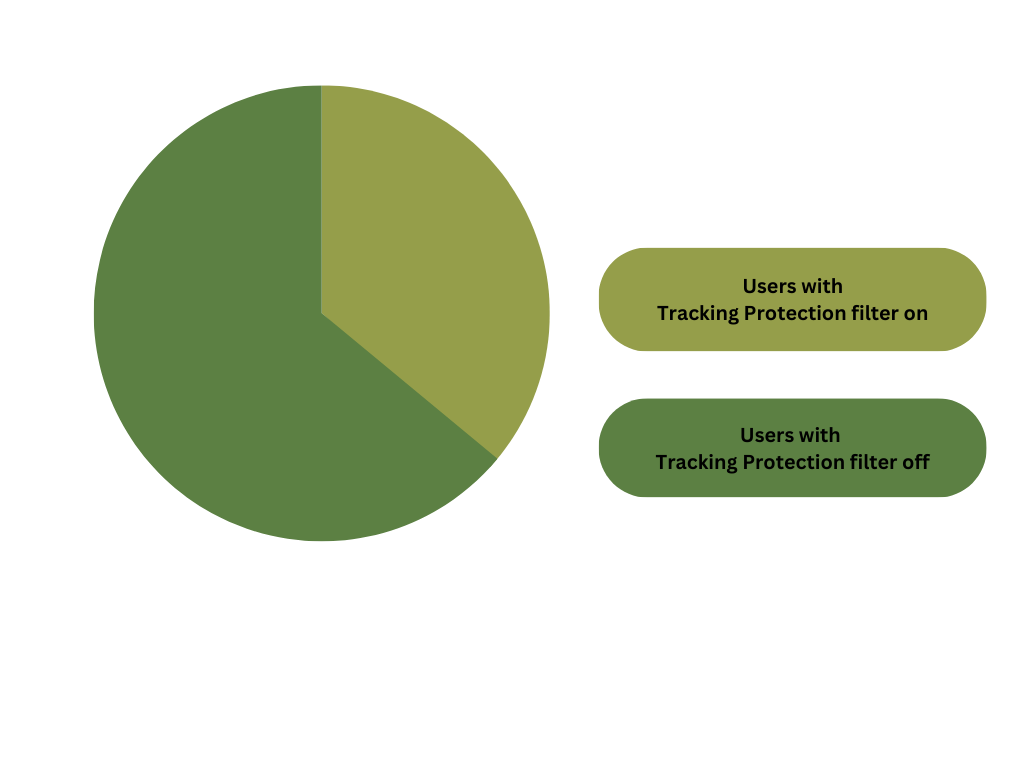

AdGuard stats: only about 36% use tracking protection

Our own data also suggests that awareness is the key when it comes to protecting your privacy. The most comprehensive anti-tracking filter in the AdGuard Ad Blocker extensions and app — the AdGuard Tracking Protection filter — is only enabled by about 36% of our global app and extension user base. This means that the majority of our users are still exposed to some of the unwanted tracking and data collection.

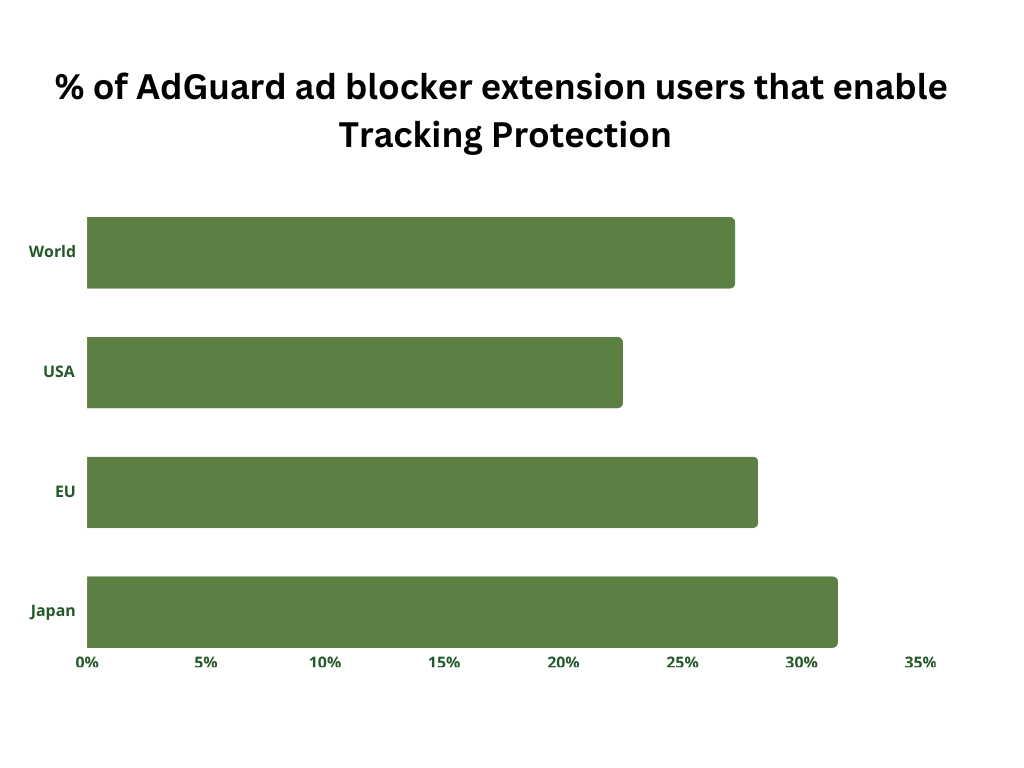

In the AdGuard ad blocking extensions, where this filter is available for free, but is off by default, only 27% users have toggled it on. It’s our guess that most who have not done so yet are just unaware of its existence.

![]()

Screenshot: AdGuard ad blocking extension for Firefox. Go to Filters → Privacy to find and enable AdGuard Tracking Protection filter

We also noticed some regional differences in the usage of this filter among our extension users. The filter is most popular in Japan, the EU comes a close second, while the US lags behind, well below the global average of 27%.

Studies, including the latest one by the Pew Research center, consistently show that people are getting more concerned about their online privacy. But they often don’t know how to act on their concerns. That’s why raising awareness about privacy protection tools, such as privacy-first search engines, privacy-focused browsers, ad blockers, VPNs, and such is important.

However, knowledge is not infallible. As people learn more about privacy tools and start to use them, they may encounter impostors, such as fake ad blockers or VPNs. They may also come across dark patterns that companies use to trick or even scare users into giving up their information. The bottom line is, however, the more you know, including about potential traps you may fall into, the worse you sleep, the better you are protected.