The history of ad blocking, part 3: Lawmaking, paid content and new tracking technologies

The final part of the History contains a brief overview of the regulation measures affecting blockers in different regions of the world. We will also see how companies dependent on advertising find other ways to earn money or track customers. If you’ve missed the previous parts or want to read them again, here there are, the first and the second.

The fourth installment of the series will be the most interesting, as we will speculate on the future of blockers.

4. The story of regulation

But governments also regard personal data as a valuable resource and see other states as competitors for it. Lobbying efforts of various market participants (advertisers, sites, technology companies) have a certain influence on the creation of any legislation, and, for a politician, protecting data is a way of gaining trust, attention, and votes.

In different regions of the world, there are different approaches to the regulation of issues related to advertising and personal data on the Internet.

The European Union shows an emphasis on the opportunities for citizens to control the collection and use of their data. As for the US president, at the moment it looks like he is more inclined to protect the interests of business. China's priority is the control over all processes and information movement, and its protection from competitors.

In our review, we will focus on regulatory efforts related to the functioning of ad blockers, because the entire review of the evolution of the state protection of personal data will be too voluminous. For example, in Russia, the main federal law "On Personal Data" was adopted as far back as 2006 and had been amended numerous times since. Tracking all the changes in Russia alone would exceed the scope of this article.

Members of the Russian Parliament at work

Members of the Russian Parliament at workApril, 2016: The European Commission issues an open letter warning that sites identifying users with blockers may violate EU legislation, as this requires access to data from these users. Hence before detecting an ad blocker, a site needs to receive the user’s consent to do so.

July 2016: China approves its own rules the rules of Internet advertising, according to article 16 of which, judging by the wording, ad blockers were in violation of the law as of September 1st of that year. However, by January 2017, it turns out that ad blocking apps are still available in stores.

Analysts believe that ad blocking can not become illegal in China because this is one of the key functions of Alibaba’s UC Browser. This is the most popular browser in China, and Alibaba is actively cooperating with the state on censorship and user data control.

UC Browser's mascot

UC Browser's mascotJanuary 2017: The ePrivacy Directive, adopted in the EU in 2009, is updated and amended on some points regarding ad blocking. Both the use of such apps by the web audience and detecting them by websites are now legalized. Web sites also have the right to react to ad blockers, for example, ask a user to turn it off.

March 2017: The European Commission adopts the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which will come into force in 2018 and which promises to change the advertising market not only of Europe.

It will be illegal for any company, regardless of jurisdiction, to store data of an EU citizen or transfer it to any other company without a formal agreement with the data operator (the company that first received this data from a user); this agreement will contain restrictions on the use of the data. To circumvent restrictions one will need to obtain the users’ consent or in some cases to notify them about the way the data is used.

As the main consequence, only the services that directly contact a user and have an opportunity to obtain his consent will be able to fulfill the requirements. This means that statistic and analytic systems and many other technologies serving the advertising market will lose the right to operate data and the very ability to work. We discussed in detail the possible consequences of the GDPR in our blog - they promise to affect companies around the world.

In the meantime, the USA demonstrates reverse trends, not toughening, but weakening the regulation of user data processing. President Obama had prepared a law obliging Internet service providers to obtain the opt-in consent of subscribers to use the data about their behavior for advertising, share and sell it (including browsing and app usage history, geolocation information, financial information, health data, and children information), but President Trump abolished this law in April 2017.

5. The story of adjustment

Marketers and publishers are looking for ways to live and achieve their goals in a world where users block advertising. Marketers come up with alternative channels and formats for delivering messages to the target audience. Media, websites, and applications are learning to make money through other means than the use of banners and advertising networks.

Native advertising

Among the most popular strategies of non-banner monetization are native advertising and paid subscription.

Native advertising has become a marketing trend for the last few years and a hot buzzword at professional events. Usually, native advertising implies creating content that is interesting or useful for the audience and promotes a brand or a product of an advertiser. The content is created at the expense of the advertiser, often by experts from its staff.

But the idea of native ads content being useful or at least entertaining is not so easy to embody. Often it just looks like a long textual ad subtly masked as an editorial. Actually, there’s nothing new or hot about paid placements in mass media, and they still damage its reputation.

But some good content does get published in the form of native ads. Experts in law, finance, real estate and other fields build personal or corporate brands by sharing their experience and advice. Other companies go an alternate way and sponsor funny and entertaining lists, quizzes, comics, "psychological" tests and other stuff of this kind. Readers usually don’t care if these are sponsored.

Considering all this, it’s still unclear what ad blockers should do with native ads. One problem is how to distinguish them, the other is whether or not they should be blocked.

And while they ponder this matter, marketers must solve not only the problem of banners being blocked but of the data being hidden and the tracking being resisted.

New ways of tracking

It’s an endless fight of the shield and the sword: advertisers find new ways to "mark" users, blockers and anti-trackers learn about them and improve their software. For example, each browser has a cache — a special folder on the device, in which various types of webpage content are stored. Most of the content is pictures, logos of frequently visited sites so that they are not downloaded from the Internet each time a user visits this site, but are opened from his device. A tracking element can be stored in cash as well. There are more complicated ways to use the cache, but the principle is this: if the user's browser requests something on the Internet, a piece of tracking code is sent along with the requested code.

Another new approach is fingerprinting. This technology, to put it simply, makes your browser draw a picture that will be individual for each browser. Browsers have a Canvas API — a set of software methods and tools for displaying graphic elements. At the hardware level, a video card and other physical parts of a computer are involved in this process, and they all have identifying characteristics that are unique to each component. As a result, each computer draws in its own way, and, drawing a picture, reports the full profile of its unique features. This profile is used to create a fingerprint.

By that fingerprint, any given device, equated here to its user, is recognized on other sites and apps throughout the Web.

Many printers put their watermarks on paper when printing, although this is usually applicable in police investigations or industrial espionage, not for marketing.

Businesses constantly find new sources of information about users and new methods of collecting it. For example, three years ago Facebook conducted a study of unpublished posts and comments. That is, the texts that people typed in fields and forms of the social network, and then deleted deciding not to send. The company analyzed the information that did not exist from the user's point of view and made some interesting conclusions about the behavior of its audience.

Actually, Facebook experts claimed not to analyze the contents of unpublished texts, they looked only at the metadata: how many letters a person typed, how many comments he wrote and did not send, at what time, etc. It was found, for example, that 33% of posts and 15% of comments on photographs have been the subject to "self-censorship" (written and deleted without publication), women practice self-censorship less often than men, and elder users — less often than younger ones. Presently, though, the text of this research is not available.

Geolocation services are a gold mine for digital marketing, but some users turn geolocation off on their smartphones. However, this is no longer a problem. Connecting ads to a physical location is still possible, as well as harvesting information about places a person visits in order to target ads on websites and in apps. A small device called a beacon can be installed inside a shop, a mall or a restaurant, it connects smartphones via Bluetooth and collects information about their owners, or sends them push notifications.

If a company manages several public wi-fi networks, it knows a lot about the people who use them.

For example, the free wi-fi in the Moscow metro, buses, trains and public places is being provided by a company called Maxima Telecom. It also has beacons in malls and shops. As a result, Maxima Telecom knows where a person lives, works, how often he visits a pharmacy, what are his working schedule is, where he likes to spend time on holidays, how much money he earns (by the stores he buys at), and so on. These digital portraits are, of course, sold to advertisers.

You don't even have to connect to public wi-fi networks in order to be tracked and targeted. Devices used for arranging these public hotspots can intercept signals that smartphones send to communicate with mobile networks.

Paid content

Finally, some services are ready to accept the fact that a certain percentage of their audience does not want to see ads, so, the service providers offer them paid subscriptions.

In 2014, YouTube launched a paid music streaming service called Music Key, which had no ads. In 2015, the service ceased to be limited to music and turned into YouTube Red. It’s funny, that even Google, whose business is based on ads, ended up experimenting with alternative means of monetization.

As for online media, a number of them already offer paid subscriptions with different implementation models. Many of these providers started this long before ad blockers became an issue. The Internet version of The Wall Street Journal was the largest paid online media in 2007 with almost a million subscribers. By 2008 there were already 15 million subscribers. However, later this amount began to decrease due to subscription price increases, and probably because there was more and more free information on the Internet. By 2010 they had only 400 thousand paying subscribers.

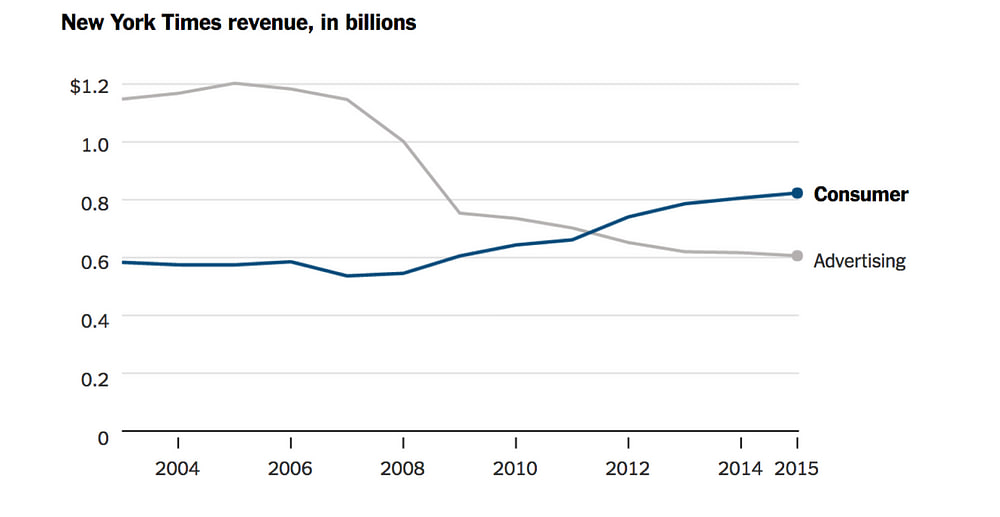

The New York Times claimed itself a subscription-first business and announced that it had 1.6 million digital-only subscriptions at the 3rd quarter of 2016, up from one million a year ago. By 2012 their revenue from subscribtions was already higher than advertising revenue.

The main challenge for paid subscription media is thought to be changing users’ mentality and behavior. There is a lot of free content on the Internet, so, why waste money? But habits and views do change, however slowly. There is indeed a lot of free stuff on the Internet, but too large a share of it is low-quality clickbait, made for attracting one's attention and directing it to an advertiser. People start to feel the point of the popular saying "if you are not paying for it, you are not the customer, you are the product being sold".