How Chrome’s 3rd party cookie replacement turns the browser into an ad auction tool

After years of delay and uncertainty, Google has finally begun phasing out third-party cookies — the cornerstone of retargeting advertising — in earnest. On January 4, 2024, just as the world rang in the New Year, Google announced that it had begun restricting third-party cookies by default for 1% of Chrome browsers. This may feel like a drop, or even a droplet, in the vast ocean. But it’s actually an important milestone. And not just because the move will affect about 32 million people, which represents about 1% of Chrome’s 3.2 billion user base.

Chrome’s rivals like Firefox and Safari (and we’re not even talking about browsers like Brave and Tor, which have made privacy their number one priority) have long blocked third-party cookies by default. So for Chrome, the world’s most popular browser, to finally join that list is a big deal. But it’s the reason behind this extensive delay that interests us the most in the context of privacy.

What took (and still taking) Chrome so long?

After first promising to deprecate third-party or “tracking” cookies “in two years,” back in January 2020, Google has struggled to come up with an adequate replacement. And for those in the know, this came as no surprise. The thing is, Google wanted to come up with a replacement that would still allow advertisers to target ads to users across websites, and be privacy-first at the same time. In other words, Google wanted to have it both ways, which is usually a tall order.

The search for an alternative was a tumultuous one indeed — the first proposed replacement, FLEDGE (short for First Locally-Executed Decision over Groups Experiment), flopped after everyone, especially ad tech companies, showed very little interest in adopting it. So Google tweaked FLEDGE, renamed it the Protected Audience API, and all indications are that this time it will stick. What’s more, it’s already being implemented, albeit for the 1% of Chrome browsers.

Protected Audience is another piece of the puzzle called Google’s Privacy Sandbox. The latter is the set of mechanisms that Google proposed several years ago and which it claims will make ad targeting more privacy-friendly. Along with Topics API — more on it here — Protected Audience API allows advertisers to continue showing users ads based on their interests, without revealing their personal information or browsing history.

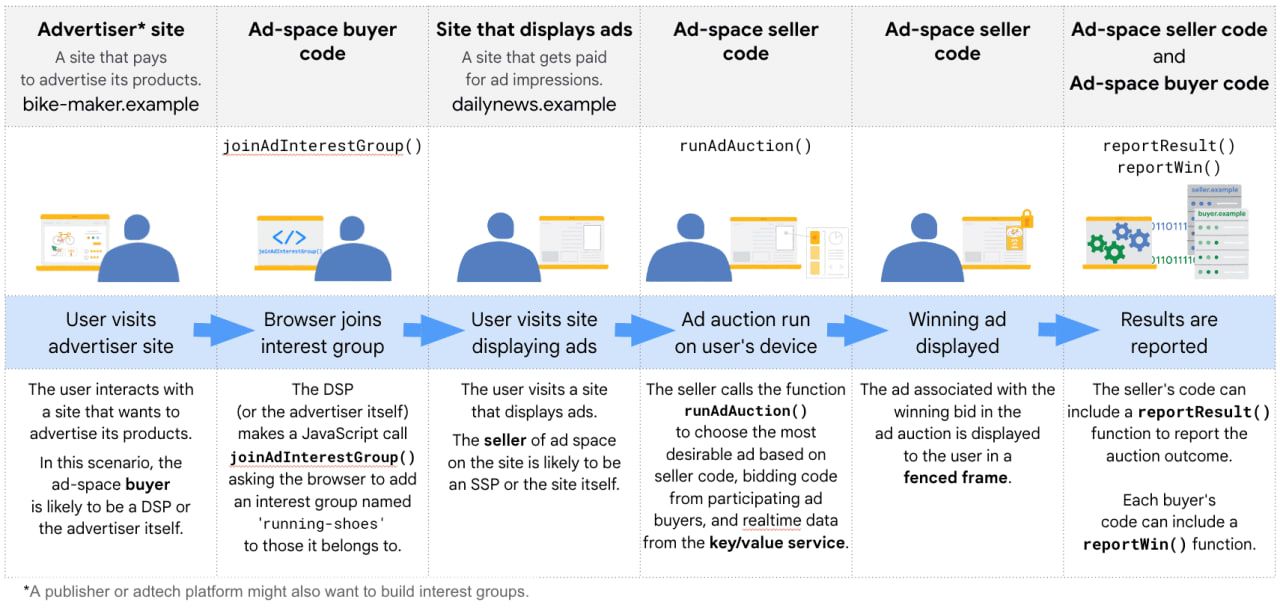

Source: Google

In a nutshell, the Topics API is a mechanism that allows the browser to observe and record topics (interest categories), while the Protected Audience API is a mechanism that allows the browser to perform on-device ad auctions on its own. In other words, Topics API focuses on what the user is interested in, while Protected Audience API focuses on who the user is and what they have seen before. In essence, Protected Audience takes on the role that third-party cookies used to play.

Is Protected Audience much better than cookies privacy-wise?

It’s tempting to assume that since the ad auctions are happening on the device, in a so-called “browser’s sandbox,” this retargeting method is, indeed, privacy-first. In fact, some even argue that Protected Audience API might not even require user consent under the GDPR.

But while Google Chrome’s cookie replacement might technically fall outside the auspices of the EU’s most important privacy law, that fact alone doesn’t make the API private. What this API does do is turn the browser itself into an instrument to show ads, an ad auction tool of its own kind.

The auction, in which the browser plays all the roles (be sure to read our detailed article on how ad auctions usually work), goes as follows: your browser joins interest groups (for example, “red wine lovers”), bids for ad space, and displays the winning ad to you.

This means that your browser may download and run various scripts and ads in the background without your knowledge or consent. In particular, your browser will constantly contact the owner of the interest group (such as an ad platform) in the background to get updates on the bidding code, ad code, and real-time data for the group. It’s true that your browser won’t tell the platforms that help advertisers sell ads (SSPs) and buy ads (DSPs) which users belong to which interest groups. But the browser itself will be privy to everything that’s going on. And the main question is: do you trust your browser that much? Or, in this case, do you trust Google (Alphabet), the world’s leading advertising company, to be in charge of your privacy?

We don’t. We believe that this solution is far from being private. If only on paper.

What is AdGuard doing to protect users from tracking

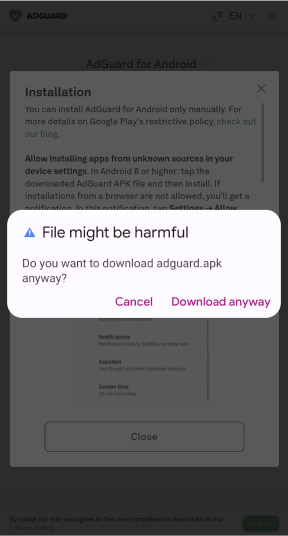

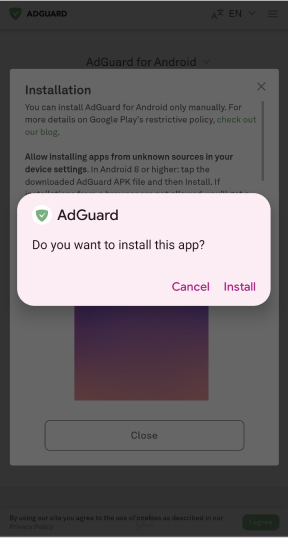

In line with our view on Google Chrome’s fraught third-party cookie replacement, AdGuard has already suppressed Google’s Protected Audience API for users who have AdGuard’s Tracking Protection filter enabled. We are also working on more advanced ways to safely disable this API, and to educate users about its risks.

We believe that privacy allows no compromises, and that our users, and people in general, deserve to be protected from tracking by default. Tracking should not be the norm, but the exception. That’s why we are committed to providing the best tools and solutions to safeguard your online privacy and security.