The new ‘pay or consent’ scheme in media: a costly illusion of choice

This year several UK newspapers began implementing a ‘pay or consent’ model, asking readers to pay if they want to avoid personalized advertising. If you think this is just more newspapers jumping on the paywall trend, don’t be fooled. The real catch is in the word “personalized” — even if you pay for a subscription, you’ll still see ads; they just won’t be targeted to you.

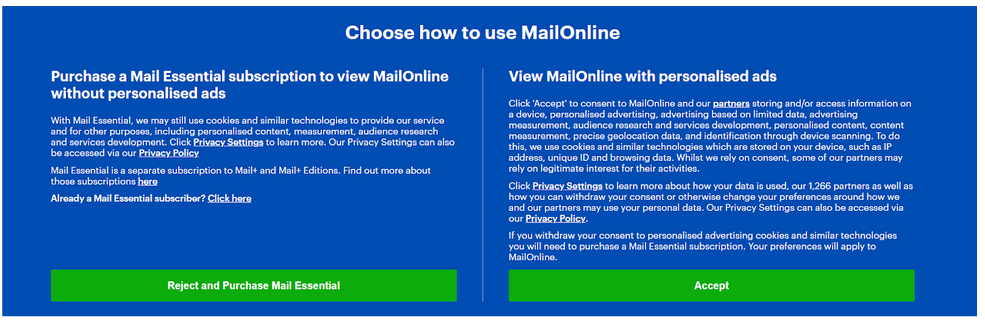

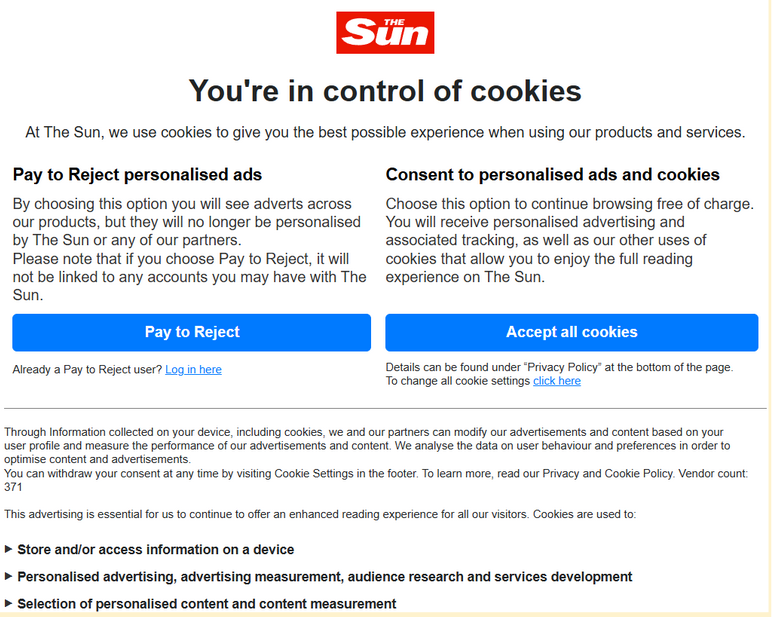

Among the major players that have embraced this scheme is The Sun, which asks for £4.99 a month, followed by The Independent at £4, and Mail Online at £2.70. Other publishers like Reach, which includes the Mirror and Express, are offering a “Privacy Plus” option for £1.99.

Most of the newspapers offer only a limited ads experience. The Independent stands out by providing an ad-free experience for its paid subscribers, but it is more of an exception than the rule.

The model is not exclusive to Britain and it’s not Britain that started the trend. Several German newspapers, such as Bild, adopted the scheme before their British counterparts.

However, its growing popularity and adoption in the UK puts it in the spotlight, especially since there is a chance it could spread further throughout Europe and, who knows, become a staple globally — particularly in countries where privacy laws have been on the rise.

A closer look at the offers

The implementation by various British newspapers (which we will focus on for the purpose of this article, as they provide a good sample size) varies. Some cut straight to the chase, offering readers a choice between accepting personalized ads or paying to prevent a website from tracking them immediately. Others display lengthy messages, making readers jump through several hoops and prompting them to consent to personalized advertising multiple times before finally presenting the ‘reject all’ option and requesting compensation.

One of the less convoluted routes is presented by the Sun, which immediately asks you either to pay to reject personalized ads or consent to them.

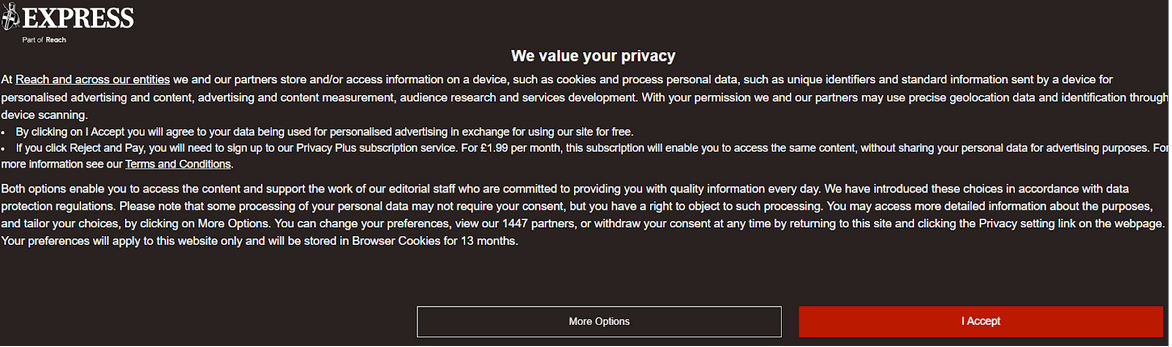

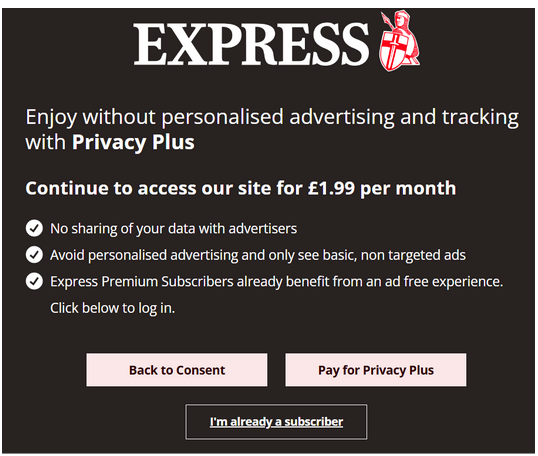

In contrast, Express makes it a little bit more difficult for readers to reject personalized advertising. The first notice prompts users to click ‘accept,’ and if they choose ‘more options’ instead, they’ll encounter a lengthy message explaining what types of information Express plans to share and with whom if the user accepts the personalized advertising terms.

That notice is a treasure trove of information by itself. From it, an inquisitive enough user might learn that if you click “accept all,” it will share your personal information, such as unique identifiers, with as many as 1147 (!) of Express’s partners.

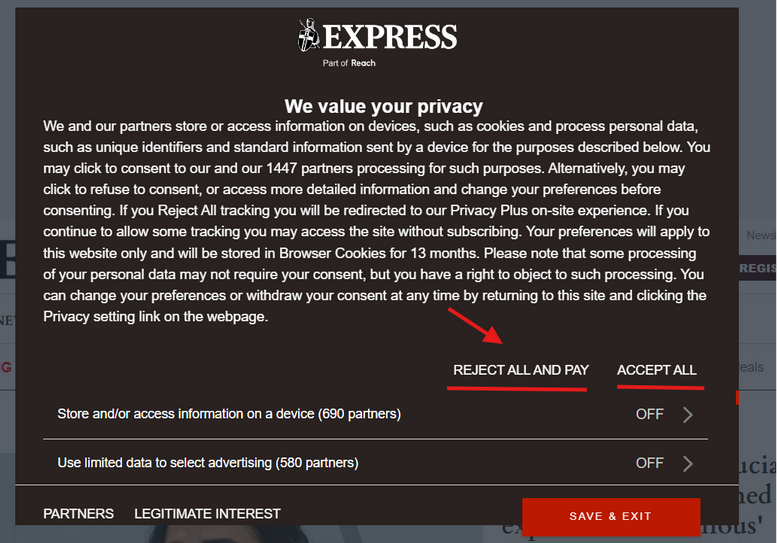

If you’re still not sold on the idea of having your personal data used to build your profile for personalized advertising — done by as many as 512 of Express’s partners — or allowing 690 of them to store and/or access information on your device, you’re finally presented with an option to opt out of tracking and personalized ads for £1.99. However, even at this point, Express isn’t giving up on its quest to gather data for personalized advertising, reminding users once again that there’s an option to go “back to consent.” The tabloid’s relentless push for tracking suggests that it might be more profitable to keep collecting data for ads rather than just collecting the fee.

Alternatively, you can manually go through the notice and adjust your preferences from off to on, but let’s be real — most people will probably just hit ‘accept all’ without even looking at the options.

The unattractive choice of the lesser evil

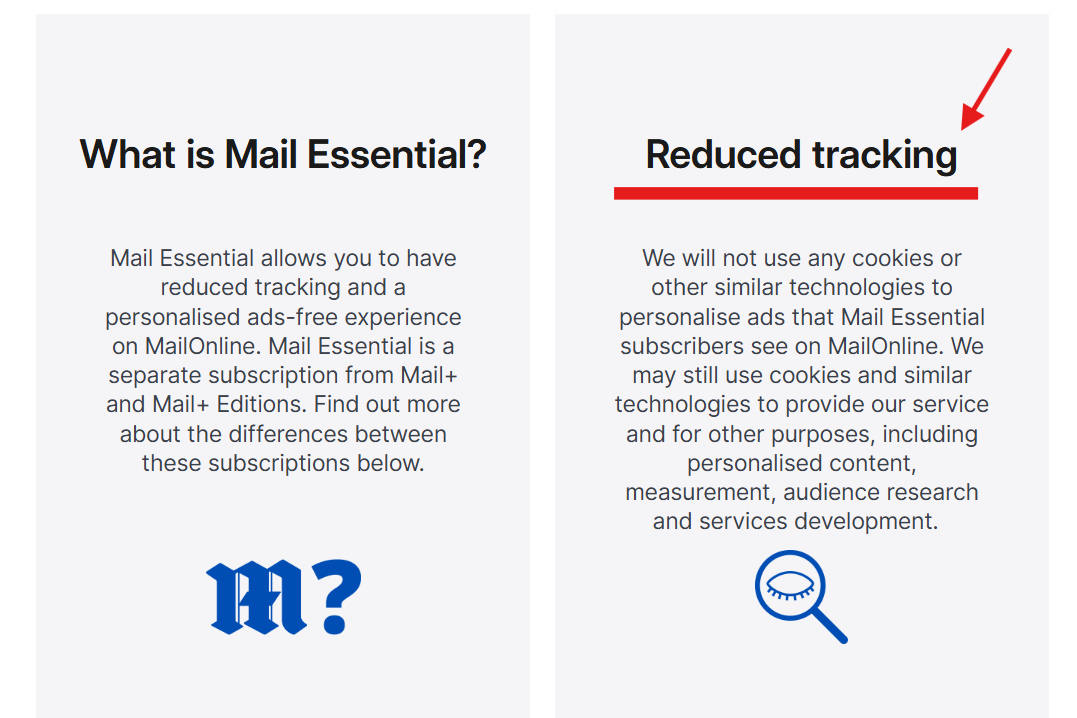

This new scheme presents readers with a seemingly simple choice: pay for a reduced ad experience or accept personalized ads (and very rarely go completely ad-free). The devil is in the wording. The Daily Mail makes it clear that the Mail Essential subscription will only offer you the option of being tracked slightly less — it’s only ‘reduced tracking,’ not ‘no tracking.’ The website will still use cookies “and similar technologies” to provide its services and “for other purposes, including personalized content, measurement, audience research, and services development.”

Similarly with ads. You will still see ads, they will just be non-personalized.

Publishers explain that this is a fair value exchange: by paying to avoid personalized ads, readers fund high-quality journalism, since personalized, highly targeted ads are known to be much more effective than generalized advertising.

However, this raises an important question: is this value exchange really fair?

In our opinion, the fairness of this arrangement is highly questionable. Paying to hide some ads (not all ads even) is hardly a compelling value proposition, especially when there is not even an option to go completely ad-free. In our view, it’s just a different iteration of advertising. And we believe that most users will reject it, even if there were indeed a genuine choice. Our recent survey commissioned through Survey Monkey indicated that most users would prefer to use ad blockers rather than pay for ad-free content.

Moreover, while the fees for opting out of personalized advertising might seem manageable for a single website, consider the implications if every site adopts this model. This choice becomes unsustainable, especially if it only leads to fewer ads or a different type of advertising. Moreover, the technology for tracking will still be embedded in these sites, meaning users remain vulnerable to surveillance.

Data privacy concerns

A big concern is what happens to the data collected before users opt out or buy a subscription, and after they cancel the subscription. The uncertainty around data retention creates serious privacy issues. Users might unknowingly create a digital footprint that sticks around, even if they later decide to withdraw consent.

This raises serious questions about how clear and honest companies are when it comes to handling data. Consumers are left feeling uneasy about what their choices really mean, especially in a situation that often feels like it’s taking advantage of them.

The regulatory backdrop or what made this scheme possible?

The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), the independent body overseeing data protection in the UK, has suggested that this model fits within data protection laws, meaning consent-based pricing could be allowed.

However, the ICO also emphasized that consent has to be “freely given” and “fully informed,” which raises some red flags considering the fees and the limitations of the subscriptions involved. As publishers scramble to boost consent rates amid falling ad revenues, the real integrity of user choice is at risk.

In short, while the pay or consent model claims to give readers more power, it ultimately creates an illusion of choice that could hurt consumer trust and the future of journalism. Many users would rather stick with ad blockers than pay for a service that doesn’t fully meet their needs.