Microsoft Edge is getting rid of third-party cookies. What about their replacement?

Following in the footsteps of Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge has announced that it would be phasing out third-party cookies. In the upcoming months, Microsoft said it plans to begin trials with discontinuing Edge’s use of third-party cookies, starting with 1% of users. These cookies, once the linchpin of targeted advertising, have been instrumental in crafting intricate user profiles.

Historically, third-party cookies — tiny data files placed on your browser by sites other than the one you’re visiting — have enabled advertisers to track your visits across all the platforms where they advertise. That’s why the role of the “tracking” cookie in spawning a surveillance economy where user data is treated as a commodity they have no control over can hardly be overestimated.

But as users have become more privacy-conscious, and regulators — primarily in the EU and California — began scrutinizing the handling of personal data, the third-party cookie has been on a steady retreat. Google Chrome’s move earlier this year to finally, after multiple delays, embark on phasing out third-party cookies was a significant blow, effectively sounding the death knell for this tracking technology. Given Chrome’s dominance in the browser market, it’s unsurprising that Microsoft Edge has followed suit. Meanwhile, browsers like Apple Safari and Mozilla Firefox, along with privacy-centric browsers such as Brave, have already been proactively blocking third-party cookies by default.

What is coming in place of cookies

In lieu of cookies, Google proposed the Protected Audience API, a part of its Privacy Sandbox initiative. The stated goal of the Privacy Sandbox is to keep ad targeting as effective as before but make it more privacy-respecting. In other words: Google wants to appease regulators and not throw advertisers under the bus either, since ad revenues are its bread and butter. To cater to both sides is a tall order, and our analysis of the proposed API shows that despite what Google says about it, it is far from being a private solution. If anything, it turns the browser itself into an ad auction tool. Our Protected Audience API demo illustrates the shortcomings of the new mechanism, which we believe can still be misused to achieve functionality similar to that provided by third-party cookies.

Unlike Google, Microsoft is not dependent on advertising profits. The lion’s share of its total revenues (about 60%) comes from Office and cloud computing. So, in theory, Microsoft’s hands should be free to come up with something really private.

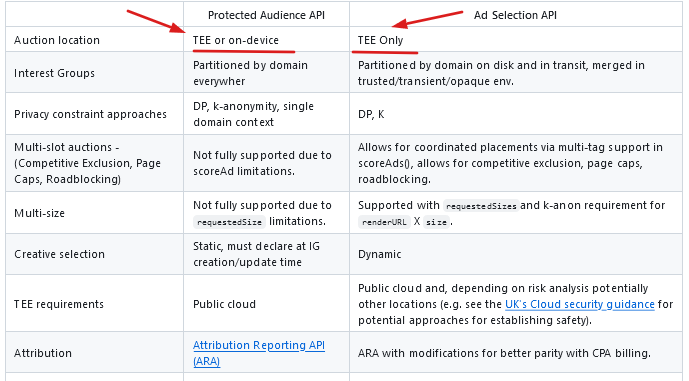

As Microsoft announced the gradual deprecation of third-party cookies, it also unveiled a new technology, called Ad Selection API, that is meant to replace them. There are uncanny parallels between this API and the one proposed by Google as you can see from the table below.

Our concerns about Microsoft’s new API

While the APIs are not identical, and there are many minor differences between them, we believe that most of them are negligible. But one difference that stands out is that while Google leaves two options for the location of the ad auction, either in the TEE or on the device, Microsoft wants to run it only in a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE).

So, what is TEE?

A Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) is a secure area within a server’s central processing unit (CPU) and memory. It’s designed to keep sensitive code and data safe from unauthorized access, including from those with high-level privileges or direct access to the hardware. Essentially, it’s a protected space where private computations are performed, ensuring they can’t be tampered with or spied upon.

Microsoft’s rationale for conducting ad auctions exclusively within a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) stems from concerns about the current scalability of on-device auctions and potential operational hurdles. At the same time they say that on-device auctions “provide a lot of value in enabling effective enforcement of privacy constraints.”

Whatever the reasoning behind Microsoft’s decision, we believe that its refusal to effectively turn the browser into an ad network is a step in the right direction. However, the robustness of this system hinges on a critical assumption: that the TEEs will remain bulletproof against unauthorized access and that no one will be able to take a “sneak peek” inside.

The server-side auctions will be run by individual ad tech companies. In Microsoft’s view, these companies can “leverage well-worn patterns for scaling, deployment, and management.” And while that’s true — indeed, these ad tech behemoths have enough resources to run these auctions efficiently — we can’t trust them by default. By designing the system this way, we will always run the risk of these companies potentially accessing users’ confidential data.

Finally, perhaps the biggest problem we have with Microsoft’s cookie replacement is that a lot of things in the specification are taken for granted. We are supposed to believe that the mere fact that user data is encrypted eliminates the possibility of unauthorized access, that the TEEs are secure environments that no one can penetrate. And if even one of those assumptions turns out to be not entirely true, or riddled with holes, then that shiny, grand vision will come crashing down. As much as we’d like to, it’s hard to believe that Microsoft, or anyone for that matter, will manage to implement such a complex mechanism with so many variables and have it work like a charm on the first attempt.

Final thoughts

Microsoft’s plan to phase out third-party cookies in favor of a novel ad targeting mechanism is quite ambitious. But there are just too many pieces of the puzzle that need to fall into place for it to work smoothly. Finding an adequate replacement for a system that has been entrenched for years is undeniably a formidable challenge, but is it insurmountable? Time will tell.

On the other hand, browsers like Safari and Firefox have long since gotten rid of third-party cookies without causing the ad tech companies to go under. Which begs an important question: How vital were these third-party cookies for the ad tech businesses, and is it truly necessary to find a replacement, or could they simply be discarded?

The answers to these questions will largely depend on Microsoft’s implementation of the new API. However, the fact that its Ad Selection API resembles Protected Audience API to such an extent raises concerns about the potential implications for user privacy.

Since we believe that Protected Audience API is not as private as Google claims it to be, AdGuard has already blocked this API for users who have AdGuard’s Tracking Protection filter enabled. In the meantime, we are working on more advanced ways to disable it. As for Microsoft’s Ad Selection API, which we believe bears uncanny resemblance to Google’s API, our approach will be the same — as soon as Microsoft implements it in Edge, we will start blocking it as well.